By Maria Telesco

Just Mercy: A Story of Justice and Redemption by Bryan Stevenson. Spiegel & Grau, 348 pages, $15.

Nobel Peace Laureate Archbishop Desmond Tutu called him “America’s Nelson Mandela, a brilliant lawyer fighting with courage and conviction to guarantee justice for all.” Regarding Esquire’s 5 Most Important Books of 2014, it was said that “there’s nobody in America who is doing more of God’s work with less acclaim than Bryan Stevenson…He is taking on the incompetence, inequities and the simple, confounded clumsiness of an overworked system that grinds up too many people and delivers far too little of what it’s supposed to deliver, both to the people caught up in it and to the country that takes such unwarranted pride in it. Stevenson…justifies that pride. If the system can produce people like him, it can be both just and merciful.”

Though lacking the authority of Tutu and Esquire, I feel qualified to say that Stevenson’s book could be the means of bringing about changes needed to fix our woefully wrecked (in)justice system. Working with prisoners, and with some of their defense lawyers, and volunteering in many prisons in many capacities for many years, I know “the system.” Experience permits me to opine that Stevenson stands, along with Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., Rosa Parks, W.E.B. Du Bois, Cesar Chavez and even Mahatma Gandhi, along with Mandela, as a shining defender of the defenseless.

Born in 1959 in Delaware, a border state Stevenson calls “more South than North,” his hardworking middle-class parents brought him up in the African Methodist Episcopal Church. When Stevenson was 16, his grandfather was murdered. His reaction to the killer’s sentence of life—rather than death—was “I came from a world where we valued redemption over revenge.” As an adult, he maintains that approach.

In childhood, he experienced racial segregation. At his elementary school, then recently (supposedly) “desegregated”—legally but not actually—Black kids and White kids played separately, White kids entered by the front door and Black kids were forced to enter through the back door.

After graduating from high school in Delaware, where he earned straight A’s, Stevenson won a scholarship to Eastern College in Pennsylvania, then received a full scholarship to Harvard Law School, where he also attended the John. F. Kennedy School of Government. During law school, he worked for Stephen Bright’s Southern Center for Human Rights, which represented death-row inmates throughout the South. There he found his career calling.

He established and is director of the nonprofit Equal Justice Initiative (EJI), which provides pro bono defense attorneys for criminal cases—many of them death penalty—in the South. The EJI challenges racially discriminatory policies, sentencing and tactics that have made mass imprisonment a crisis in many communities of color. Stevenson is a professor at the New York University School of Law, maintains an active career as a criminal defense and appeals attorney in all states, not only in the South, where his skills are needed.

Stevenson doesn’t hesitate to say what’s gone wrong with the nation’s (in) justice system; he has nailed it 100%. We have the world’s highest rate of incarceration, brought about by a “radical transformation” of the 1980s that turned us into a “harsh and punitive nation.” In the 1990s, states abolished parole, switching to “three strikes and you’re out.” Crimes previously considered minor, such as writing bad checks or shoplifting, are now subjected to draconian sentences like life in prison without possibility of parole. He says we institutionalized politics that reduce people to their worst acts and permanently burden them with lifelong criminal labeling they can never change no matter how hard they try to better themselves. He says each of us is more than the worst thing we have ever done.

Stevenson writes of poverty, racial bias and “presumptions of guilt,” and systems full of error and corruption, as being responsible for thousands of innocent people suffering in prison. Private for-profit prisons and the corporations building them, consuming millions of taxpayer dollars, lobby governments to create new crimes and impose harsher sentences, to keep cells full and profits burgeoning. Private profit has corrupted government incentives to improve public safety, reduce mass incarceration and promote rehabilitation of the incarcerated.

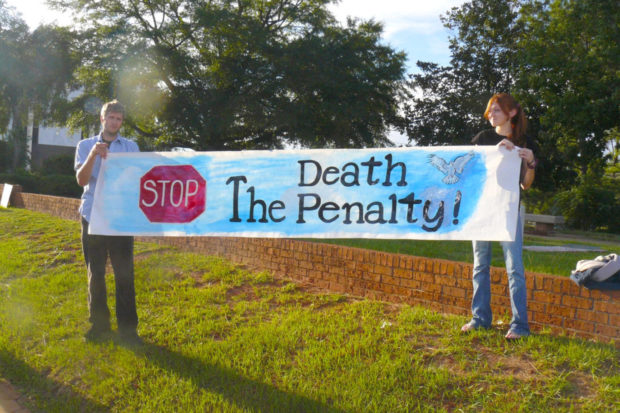

He discusses many cases of innocent people being wrongfully convicted of homicide and sentenced to death row due to errors and perjury. The story of Walter should soften the heart and readjust the mind of even the most devoted worshiper of the death penalty. Walter was eventually exonerated; others, wrongfully convicted, less lucky, have been executed. Stevenson describes how the power of the victims’ right movement, emerging about 40 years ago, influences court decisions, making them more severe, with more death penalties, which accomplish nothing beneficial. He says that “the death penalty is not about whether people deserve to die for the crimes they commit. The real question is, Do we deserve to kill.”

Just Mercy also speaks for imprisoned children. Thousands, sentenced as adults, are sent to adult prisons, nearly 3,000 sentenced to life imprisonment without possibility of parole. Children as young as 13, tried as adults, are sentenced to die in prison, without consideration of age or circumstances of the offense. The EJI argued in the U.S. Supreme Court that death-in-prison sentences imposed on children are unconstitutional. The Court has since banned such sentences, both for children convicted of non-homicide crimes, and mandatory death-in-prison sentences for all children. The Supreme Court wrote that because of “children’s diminished culpability, and heightened capacity for change, we think appropriate occasions for sentencing juveniles to this harshest possible penalty will be uncommon.”

Fourteen states have no minimum age for trying children as adults, allowing some as young as eight to be prosecuted as adults. Some states set the minimum age at 10, 12 or 13. The EJI believes prosecution of any child under age 14, for any crime, should be banned.

Daily, some 10,000 children, being housed in adult jails and prisons in America, are five times more likely to be sexually assaulted in adult facilities than in juvenile facilities and face increased risk of suicide. The EJI believes incarceration of children with adults indefensible, cruel and unusual, and it also should be banned. For children with parole-eligible sentences, release and reentry challenges often create insurmountable obstacles to successful reentry.

Just Mercy is more than an overwhelming I-can’t-put-it-down read; my years of experience with prisons and prisoners tell me every word in it is right on. Innocent people are on death row and in general population, often put there by prosecutorial misconduct. Young people who have been in prison since they were adolescents need help learning basic life skills. I’ve worked with some of them who went to adult prisons as teenagers and don’t have the faintest clue about living as an adult in an adult world; the prison systems do little to prepare them for those transitions. How are they, without help, to get along in the world outside of prison?

The American people need to be awakened to the reality that our barbaric broken (in)justice system needs desperately to be remedied. Because it won’t fix itself, it’s the duty of us, “the people,” to make it happen. Just Mercy gives us the initiative and guts to get started before it’s too late.

*****

Maria Telesco is a retired registered nurse who has volunteered in various aspects of prison ministry for more than 25 years. Contact her at maria.telesco@sbcglobal.net.