Fresno’s infamous Bitwise Industries saga continues as court proceedings are scheduled this summer, and chatter persists about the embroiled company and its scheming co-CEOs, Jake Soberal and Irma Olguin Jr.

The pair faces a charge of conspiracy to commit wire fraud. The prosecution says they bilked investors and lenders of $100 million. They could spend 20 years in prison and be forced to pay a $250,000 fine.

It is expected they will make a plea bargain.

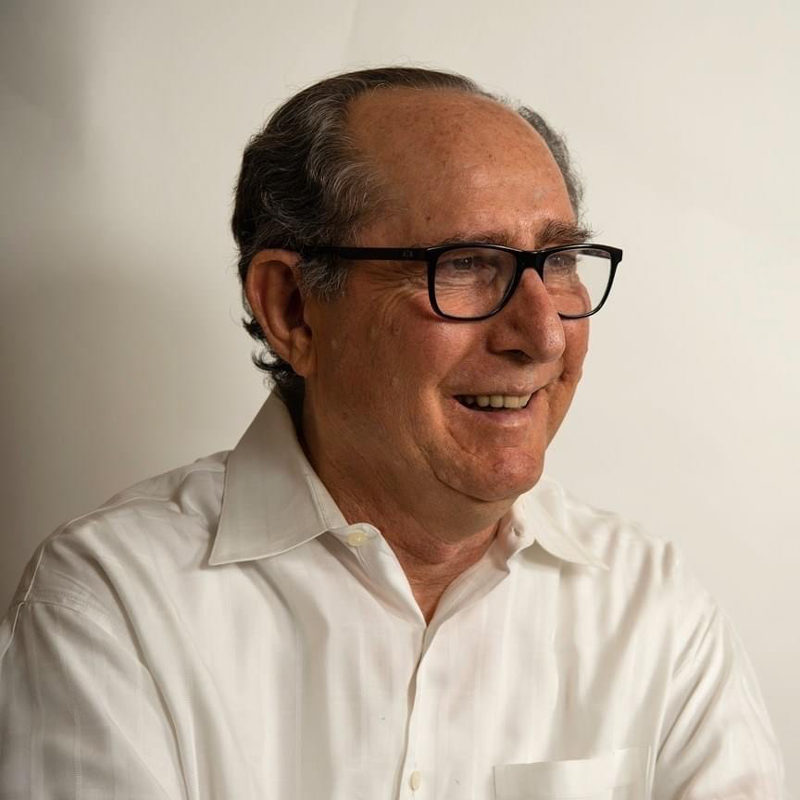

Mark Arax, Fresno’s bestselling author of The Dreamt Land and The King of California, saw a side of Bitwise that was different from what most people experienced. Because he had a friend who was an early Bitwise investor, Arax found himself in a room with Soberal and Olguin at the company’s inception in 2013.

“About halfway through that meeting,” Arax recalled, “I just got this kind of creepy sense that they were too slick for their own good—especially Soberal—and that the model of what they were trying to do just didn’t make sense.”

A year or so later, Arax’s investor friend got “fleeced” but was “too embarrassed to really talk about it or bring a lawsuit.” Arax tried to have a Bitwise contractor build him a website, and that was a failure, causing him to write several letters of complaint to the company. Family and friends took Bitwise classes in coding but came away saying that they knew more than the instructors.

After a while, Arax said, “Whenever I went talking to city leaders and state leaders, and the Bitwise subject came up, I would tell them that I thought that Bitwise was just a Ponzi scheme.

“There were people, maybe you could call them ‘Cassandras,’ I don’t know. There were people sounding the alarm asking, ‘what is this thing?’ But no one wanted to listen.

“At the end, Soberal and Olguin got so desperate they were hitting up all these westside farmers and other wealthy people in Fresno in an attempt to bail Bitwise out. Some of them gave some dough thinking that they were going to triple and quadruple their money.” Instead, those people lost it all.

Arax makes a keen analogy between Bitwise and the classic musical, The Music Man. The story line is that a con artist, Harold Hill, comes to a medium-sized city in the Midwest, River City, and convinces folks that they are in cultural peril. Then he sells them on the idea of him leading a marching band for their children as a kind of social panacea.

The truth is that Hill actually knows little about music and is just after a quick buck. Finally, the citizens of River City find out he’s a grifter but they are so taken by the sight of their children in uniforms managing to play a little music on their instruments that they forgive him.

Bitwise offered a social panacea to Fresno—tech training for youth from Fresno’s underserved communities and tech help for small businesses. Fresno was big enough to have resources to draw upon but not so sophisticated that officials or the public would find out what was really going on. Three mayors in succession were Bitwise supporters.

“Like The Music Man, they [Soberal and Olguín] were selling flim-flam,” Arax said.

Miguel Arias, the Fresno City Council member representing downtown, explained how Bitwise for him was a mixed bag. Aside from the criminal behavior and the disaster of the company’s implosion, Arias had reasons to appreciate it.

Arias explained, “The reason I liked them [at first] is that they were a company that never received a penny of City funds. Most of these big companies, to relocate in Fresno or to expand in Fresno, always ask for incentives. Amazon was given $30 million. Alta was given $17 million. The Gap was given $10 million in incentives.”

Bitwise was a unique company, he said, because it “had grown to about 500 employees in Fresno without ever receiving any incentives from Fresno or any waivers of fees.”

Arias also emphasized Bitwise’s modernization of historic buildings. “The old way of ‘Fresno thinking’ when it comes to downtown development was to tear down the building, the historical building, and start from scratch. It’s cheaper. Very few developers went and renovated the existing buildings because they didn’t believe there was a market for them.

“Bitwise demonstrated that there was a market for renovated old buildings. And that’s why all their buildings are fully leased.”

When the pandemic occurred, the U.S. government made $10 million in American Rescue Plan funds available to the City of Fresno for nonprofits. Many applied, and Bitwise, through its nonprofit arm, was approved for $1 million. It was meant to be spent on “digital empowerment.”

Per the terms of its agreement with the City, Bitwise needed to spend its own money on the program and then get reimbursed. “We [the City] don’t give you a million dollar check,” Arias said.

Before being reimbursed, Bitwise had to invoice the City for work done, showing documentation—receipts and invoices—that the work took place. Bitwise’s nonprofit arm did much better bookkeeping than the corporation; it acted legally and fulfilled the agreement for three months, spending $100,000 per month.

“They had been awarded money to train small businesses in expanding and doing social media advertising and marketing,” Arias said. “If you were, like, an up-and-coming street vendor and you don’t have an Instagram, you don’t have any social media, they were contracted to help you do that.

“The thing about the Bitwise experience [with the City] is that everything worked the way it was supposed to.” Until it didn’t.

“By the time we caught on and this whole thing went public, we had cut them a check of about $300,000 for the first quarter.” Bitwise never saw the other $700,000. Arias said it was the only time in five years that money awarded by the City was not totally disbursed.

Andrew Janz, Fresno’s City attorney, seconded Arias that the City of Fresno was not ripped off by Bitwise. “It’s fair to say that a lot of people are disappointed, and a lot of people have hurt feelings over the issue,” he said. “That’s obvious.”

However, he added, “My understanding is we had proper procedures in place to safeguard against any fraud against the City.”

“At the end of the day,” Arias concluded about Bitwise, “when all the chips fell, they had 75 marketing specialists, 75 marketing specialists!

“A $4 billion organization, [the] Fresno Unified [School District], with 10,000 employees, has one marketing person. A hospital system—Valley Children’s or Community Medical Center—with billions of dollars of assets might have two or three marketing people.

“Yeah. Seventy-five marketing people? Crazy! So who was generating the revenue?

“Those folks should be in the movie production business; they were a master class in painting the picture that everyone was desperate to buy.”

Arax said, “The power of wanting to believe is really an extraordinary force. That’s one of the major elements in many of these cons—it was an illusion.

“The whole thing was an illusion.”

Thanks for an up to date summary of the fall of Bitwise. I believe a movie will be done on the technological hope of the City of Fresno and the financial ignorance and greed of two tech entrepreneurs that lead to the downfall of Bitwise Industries. A lot of young people lost their careers and jobs when Bitwise crashed, one of them was my son who was starting a career as a software engineer at Bitwise.