It started with a deceptively innocuous Facebook post made by newly elected Clovis City Council Member Diane Pearce. On June 28, toward the close of Pride Month, she warned her constituents, “Might want to wait until June is over to take your kids to the Clovis Public Library,” the caveat accompanied by a bit of “evidence”—a photo of a modest library display of LGBTQ+ books for kids.

This was not the first time Pearce, whose day job is managing her husband’s Elvis-impersonation business (“Call or text Diane” to order merch or request a booking!), had posted provocative remarks on her City-branded Facebook page. A native Fresnan and newcomer to Clovis who lost her first bid for City Council, Pearce was sworn in for her current term only in January.

At the May 8 Clovis City Council meeting, Pearce made a rather confusing proposal to change the administration of the City’s flag policy from the city manager to the City Council. However, the Council voted 4-1 to keep the current policy (with Pearce opposing). Pearce then engineered a time- and resource-consuming issue regarding flag display.

In Clovis, the city manager is responsible for administering the flag policy. The policy itself—no flags raised on City property except for the U.S. flag, the state flag and the flag of the city of Clovis—was agreeable to all, including Pearce.

Despite that unanimous agreement, simply because the Council declined to change the management of the flag policy, Pearce subsequently posted a video on her Facebook page in which she stood before a Clovis city flag, wearing a shirt emblazoned with the City logo, and insinuated that her fellow Council members were unpatriotic and unsupportive of the U.S. flag. Her Facebook post screamed, “FACT: THERE IS NO COUNCIL-APPROVED FLAG POLICY IN THE CITY OF CLOVIS!” [sic].

Naturally, her colleagues on the Council—all fellow Republicans—were deeply affronted and publicly expressed anger that, after agreeing not to shift the administration of the flag policy, Pearce had, after the fact, solicited supporters to show up to the next Council meeting to comment in her favor.

Mayor Lynne Ashbeck remarked that in 22 years on the Council she had “never seen someone who doesn’t win a vote then take it to the public.” In response to Pearce, a few members of the public showed up on May 15 to question the patriotism of the other Council members and describe their opposition to the raising of the Pride flag, which was at the heart of Pearce’s proposal.

Pearce was following the lead of Supervisor Steve Brandau, who had brought the same issue before the Fresno County Board of Supervisors (BOS). Brandau, Pearce and others have made flags an issue after local reactionaries opposed raising the Pride flag at Fresno City Hall.

About 50 pastors and members of evangelical Christian groups from Fresno and Clovis who espouse right-wing ideologies were signatories to an anti-LGBTQ+ statement made in response to Fresno Pride events in June 2022. The letter described “deep disapproval” of public display of the Pride flag. Ensuring that the Pride flag would not be flown in Clovis was Pearce’s aim.

Attempts to ban the Pride flag and ban LGBTQ+ books are issues that are not unique to Fresno or Clovis. They are not happening in a vacuum. Books about LGBTQ+ people are targets of what the Washington Post calls a “historic wave” of nationwide attacks and challenges, with most of the complaining coming from individuals filing scores of serial complaints with their local libraries. Right-wing fringe groups such as Moms for Liberty often organize volunteers to make the complaints.

Presumably, a city flag policy covers flags raised at public schools. The ACLU has said that “Rainbow flags, Pride flags and other symbols celebrating LGBTQ pride are a protected form of free speech in school settings,” per First Amendment protections for students in public schools.

Legal arguments aside, the Pride flag is a symbol of welcoming to a heretofore marginalized and persecuted group, and, on an emotional level, banning it conveys a message that this still-vulnerable group is not only unwelcome but also that abuse is permissible. Many recent reports of violence we see in the news, such as the murder of a woman in San Bernardino County, shot to death by a man who objected to the Pride flag in front of her store, evince this outcome. The same dynamic applies to book bans.

Pearce’s June 28 Facebook post about the Pride book display drew attention and alarm from the LGBTQ+ community, and by July 10, there were 237 comments posted in response, all but a handful in opposition to her. At the July 10 Clovis City Council meeting, five members of the LGBTQ+ community and supporters were present to publicly object to Pearce’s remarks and to question why Pearce was permitted to circulate them on her City-branded social media.

One commenter was Jennifer Cruz, a longtime Clovis resident, parent and manager of the Fresno Economic Opportunities Commission (Fresno EOC) LGBTQ+ Resource Center. She said that Pearce’s comments were dangerous, that they compromised the safety of the library and that urging constituents to avoid the library promotes fear and misinformation about the LGBTQ+ community.

In her job as manager of the Resource Center in downtown Fresno she “sees the suffering of our community every day,” including the “real-life consequences” of the hatefulness in remarks such as those made by Pearce. Mayor Ashbeck noted that 10 letters in opposition to Pearce had also been received.

Pearce, however, was unmoved. She claimed to be the target of “vitriol, hate and venom” herself. Ashbeck, to her credit, vehemently reprimanded Pearce, remarking that Pearce’s opinions “have no place in building a community” and that she had deeply offended City staff, some of whom are Black, or gay, or have trans kids.

(In a February Council meeting, Pearce had objected to the term equity appearing in a proclamation honoring the African-American Historical and Cultural Museum because she felt “equity” was “socialist.” The statement had angered Black staff members.)

Ashbeck pointed out to Pearce that matters regarding the county library, of which the Clovis location is a branch, are not within the City’s jurisdiction. Issues that “we can’t control don’t belong in this chamber,” she noted.

“Go on KMJ and talk as an individual,” Ashbeck said to Pearce, but don’t speak publicly as a member of the City Council. (Pearce hosts a radio show on KMJ.)

“We have families here who like to read those books—let them read ’em—you don’t have to read them,” she admonished Pearce.

Pearce’s social media use in general, which she appears to undertake on behalf of the City of Clovis, has raised particular concern. At the Aug. 7 Council meeting, Tracy Bohren, a Clovis resident, asked the Council to adopt a policy for Council members’ social media code of conduct.

Alluding to Pearce’s controversial social media posts emblazoned with the City logo, Bohren said that the remarks cause confusion between personal opinion and City policy and noted that government officials’ social media posts are subject to laws such as the Brown Act and other statutes regulating public records.

At the close of the Aug. 7 Council meeting, Pearce demanded of her Council colleagues an impromptu consensus to direct the city manager to draft a letter to the county BOS regarding what she now called “graphic sexual content in children’s books” in the public library because the library is in the county’s purview. Two other Council members agreed to sign, but Ashbeck said she would never sign such a letter.

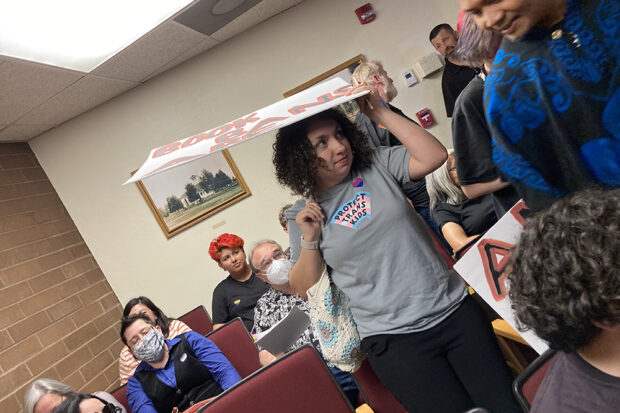

At the Sept. 5 Council meeting, there was a powerful showing of queer Clovis youth and allies, who showed up to resist the bigotry and danger of public statements such as Pearce’s. A proposal was on that meeting’s agenda to send a letter to the BOS informing them of alleged “community concerns” about children’s books in the library that feature “graphic sex acts.”

The letter, drafted by City Manager John Holt at Pearce’s direction, was appended to the agenda. Those who wanted to comment publicly were lined up out the door into the lobby. It took more than two hours, with each speaking for about three minutes each, to hear everyone.

About seven people spoke in support of Pearce and the letter, and the other 40-plus who spoke in opposition included many local LGBTQ+ high school students, older members of PFLAG Fresno, retired librarians, a retired social worker who pioneered adoption for gay parents and other parents from the community. Many disclosed deeply moving personal histories.

After the lengthy public comment period, the Council voted unanimously to “do nothing” about the proposed letter. Individual Council members, it was decided, were free to send letters on the City letterhead if they wanted to.

The next day, Pearce, on her City Council–branded Facebook page, misrepresented what happened. She said that she had “voted against” the letter drafted by the city manager, but there was not a “no” vote. The vote was to “do nothing.”

She posted a copy of a letter addressed to BOS Chair Sal Quintero that she had written herself and falsely said that the letter drafted by Holt “fell short of what a majority of the Council agreed to at our meeting on August 7.” There had been no agreement on Aug. 7, which was why the draft appeared on the Sept. 5 agenda.

Pearce’s protestations that she “didn’t want to ban books” and that she was only seeking to ensure that books found in the public library were “age-appropriate” were belied by her many public statements, such as that LGBTQ+ people were “going after the kids” and that “no child can be both boy and girl or the opposite gender that he or she was born,” or that she was only trying to “let people know” about the presence of the books so they could make “an informed decision.”

Ashbeck emphasized that “Clovis is a welcoming community. Our job is to build community. People are welcome here. They need to be safe here.” But she lamented all the time and effort spent that evening because it didn’t make Clovis “a better place.”

Council Member Vong Mouanoutoua said that he learned a lot from hearing personal stories, and he found value in that.

Ashbeck agreed that “we have to hear each other” but that “we didn’t solve anything.” Perhaps she just wanted to get on with the City’s business without further distraction.

Nevertheless, it was an extraordinary several hours in Clovis, when an exceptionally rich gathering of members of the LGBTQ+ community and their allies showed up at a City Council meeting to eloquently insist on their rights. As Mouanoutoua said, “I’m wiser now.”