A photo essay by David Bacon

Gov. Gavin Newsom acknowledged last week that the coronavirus crisis is expanding far faster among eight rural counties in California’s Central Valley than in the state’s highly-populated urban centers. The 29,200 cases those counties reported in the last two weeks are more than eight times the number reported at the beginning of May. For every hundred people tested, the number of positive results ranges from 11 in Fresno to 26 in Kern. The hotspots, the governor declared, include Latino communities and essential workers.

In counties like Tulare, essential workers and Latino communities are often the same people –overwhelmingly the families working in the fields and packing sheds, cultivating, harvesting and processing fruits and vegetables. Tulare County produced $7.2 billion in fruit, nuts and vegetables in 2018, making it one of the most productive agricultural areas in the world. Tulare’s farmworkers, like those in these photographs, create that wealth.

Yet the per capita income of a county resident is $20,421 per year, compared to a U.S. average of $32,621, and 107,541 of Tulare’s 484,423 residents live below the poverty line. Poverty has its price. It forces farmworkers to continue working during the pandemic, when people are well aware of the danger of illness and death. Tulare County’s COVID-19 infection rate (1.96 percent of the population infected) is much greater, per capita, than those of large cities like San Francisco or Sacramento. On August 2, Tulare had 9,520 confirmed cases and 178 deaths. Alameda County had 11,590 confirmed cases and 189 deaths. But Alameda County’s population is 1.68 million, over three times that of Tulare County.

Poverty’s price is also visible in the spray-painted tags and holes punched in the walls of the local shooting gallery, an abandoned house on a back road used for parties and drugs. When Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez was called a “fucking bitch” for saying that crime has roots in unemployment and poverty, she could have been describing the scene in that building’s dark rooms.

Another price is paid by people forced to live outdoors. Tulare County has 814 homeless people, 70 percent of whom are unsheltered. By comparison, in California as a whole 72 percent of the state’s 151,278 homeless people live without shelter. “Sheltered” or “not sheltered” might be a distinction without a difference, however, to the many who live in a string of encampments along the often-dry watercourse of the Tule River. Some have built shacks, some park small trailers in the underbrush, and some just sleep on the ground.

Walking through the levee settlements, Arturo Rodriguez and Mari Perez offer to bring food collected at the community center they’ve organized in Poplar. The Larry Itliong Resource Center opened in June, as pandemic cases mushroomed. They named it for the famous Filipino leader of the 1965 Grape Strike and co-founder of the United Farm Workers. The center is a former fire station on Road 192, in the middle of the fields and orchards surrounding this tiny unincorporated community of 3,000 people. From the storefront office a host of volunteers, recruited by Rodriguez and Perez, fan out to bring food to COVID-affected communities all along the Tule River and beyond.

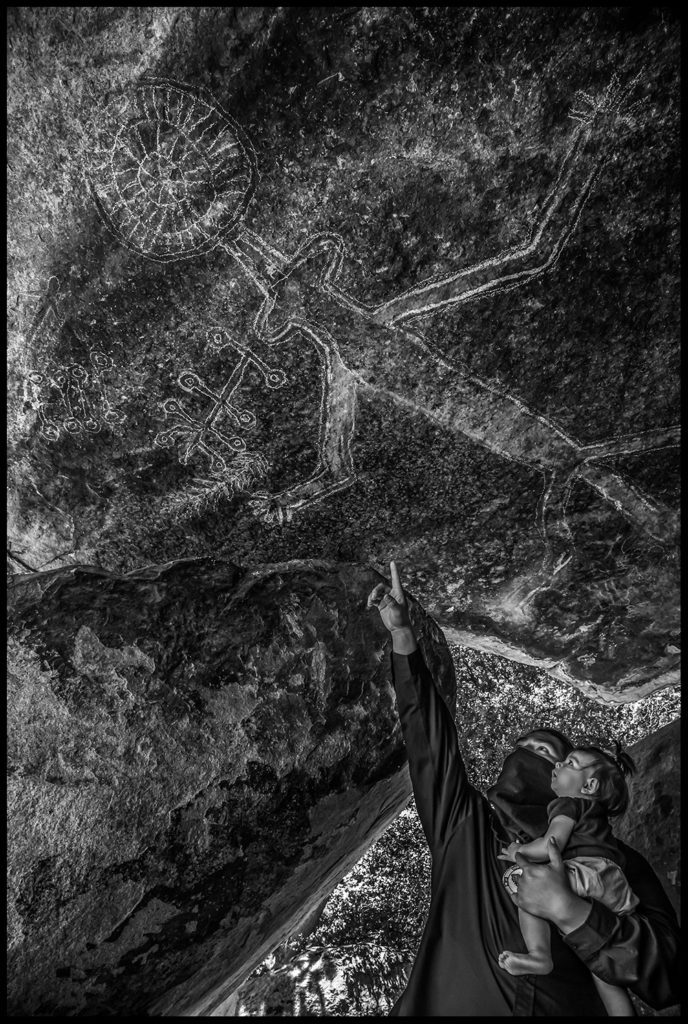

Tulare County, for all its wealth, is a community of the dispossessed, and that dispossession has a long history. It started with the entrance of white settlers into the San Joaquin Valley in the mid-1800s. The years of the Gold Rush, when California became a state, was also the era when agriculture in Tulare County began. The original people who lived on the valley floor, near the now-vanished Tulare Lake, and in the surrounding foothills, were repeatedly and violently attacked by newcomers greedy for land.

The U.S. government broke all 18 treaties it signed with California’s indigenous tribes and forced them onto reservations. When the reservation land in what is now Tulare County proved desirable to settlers, the government forced the native people into the hills. The Tule River became the source of the irrigation water that made the county’s farming possible. Today the river water is gathered behind a huge earthen dam at Lake Success, just upstream from the homeless encampments.

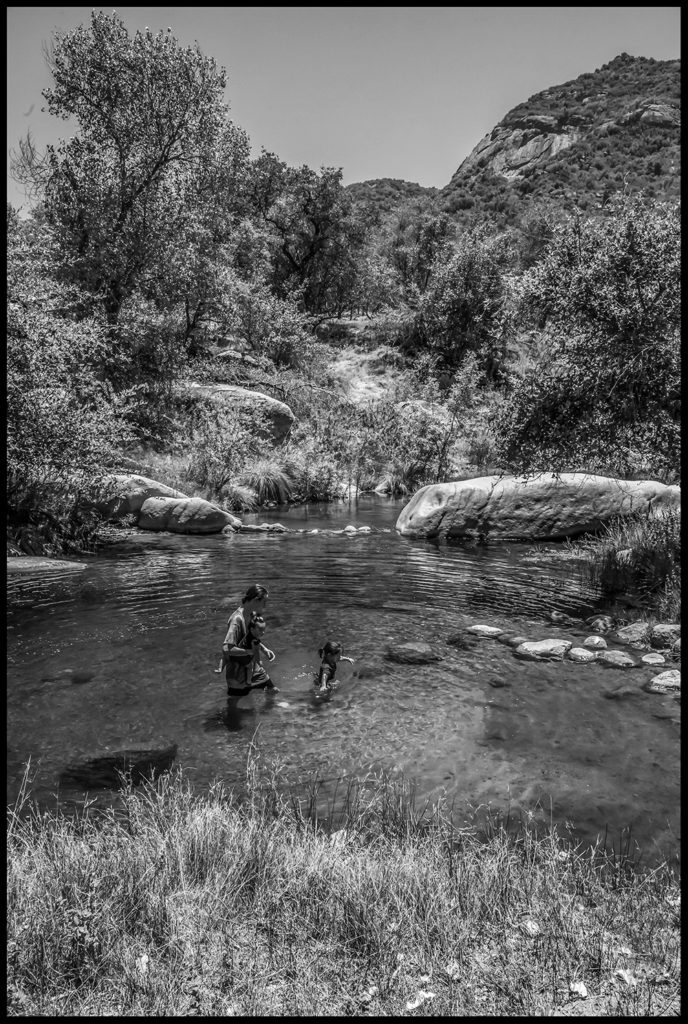

Further upstream is California’s largest Indian reservation, of the Tule River Tribe of the Yokut, Mono and Tübatulabal peoples. But while the water flows through the reservation, its inhabitants have no right to use it, having been robbed of their water rights in 1922. The estimated poverty rate on the reservation is 50 percent higher than for Tulare County as a whole. Testifying before Congress in 2009, Tribal Chairman Ryan Garfield charged that “Families living on the Reservation do not have consistent running water in their homes and are forced to collect buckets of water from the South Tule River for cooking, drinking and cleaning. Water supplies in local schools have been dramatically reduced causing increased illnesses and creating cleanliness issues. … They too deserve what every American should have – a sanitary water supply to grow their crops, feed their families and provide a clean safe home.”

The Tule River, or what’s left of it, leaves Lake Success and flows west through Porterville, past Poplar, towards the former bed of Tulare Lake. The lake, with its abundant fish and birds, vanished in the 1930s in one of the great ecological tragedies of California. The Tule, like the other rivers that fed it, eventually splits into channels and disappears into irrigation canals that water the valley’s dry west side.

Speeding south down Highway 99 through the San Joaquin Valley, passing Tulare city, the savvy traveler notes the enormous International Agri-Center as it flashes by on the right. Its huge buildings and farm vehicles testify to what the economy of Tulare County has become.

Yet as these photographs show, it is an economy that does not serve everyone. Mari Perez and Arturo Rodriguez still leave the Larry Itliong Resource Center in the morning and continue to bring food to the hungry. Tulare’s crops still grow on land taken from the native people, forced into reservations in the foothills. Landless farmworkers –dispossessed migrants from Mexico– still provide the labor. Now the virus cuts its swath through the county’s most vulnerable, exacerbating these age-old inequalities.

*****

David Bacon is a journalist and photographer covering labor, immigration and the impact of the global economy on workers.