By Vic Bedoian

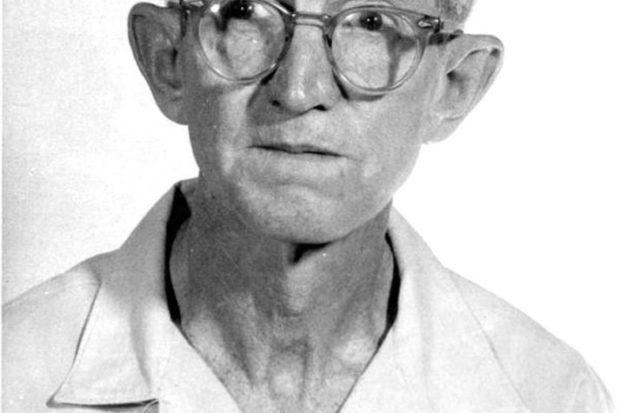

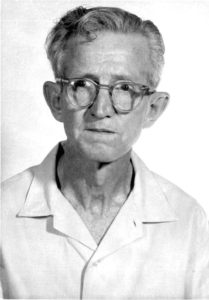

This year marks the 50th anniversary of the landmark judicial decision regarding the right of everyone to a fair, speedy and effective day in court regardless of their economic status. In 1963, the U.S. Supreme Court in Gideon v. Wainwright established a legal principle and underscored a constitutional right that many Americans probably think had been recognized long ago. After all, the Sixth Amendment to the Constitution was part of the original U.S. Bill of Rights ratified by Congress in 1791. However, it took Clarence Earl Gideon, a homeless man with an eighth-grade education, to confirm that right for all the rest of us. Although that time-honored entitlement is by now well-established in law, it is still a work in progress and faces severe challenges because of the harsh economic conditions and prosecutorial policies that exist today.

David Carroll of the Sixth Amendment Center is a Boston-based attorney and expert in the principle of public defense, “Gideon was someone who was in and out of the criminal justice system. He was poor and he was charged with the crime of breaking into a pool hall and stealing a couple cans of soda and some money from the pool hall, not a lot. He was brought to trial and at that time in Florida there was no right to counsel for felony cases. There was only a right to counsel if it was a capital case.”

After the judge refused a defense attorney, Gideon did his best to defend himself. Carroll continues, “He questioned people and witnesses but he was a layman, he wasn’t well educated, he didn’t know criminal procedure on what could be admitted and what couldn’t be admitted in court, and he was very quickly found guilty and sent to jail.”

From prison, Gideon submitted a handwritten letter to the U.S. Supreme Court stating that he was unjustly put in jail because he believed he was entitled to a lawyer and didn’t get one. The Supreme Court agreed unanimously.

In assessing the case, Carroll observes, “Criminal case law is too complicated, you can’t possibly know if you’re jeopardizing your own liberty. If states are going to bring the machinery of law enforcement down to try to take away individual liberty, there has to be someone there to protect your interest. And the interesting thing about the Gideon case is that when the U.S. Supreme Court sent the case back and said there has to be a new trial, Gideon got counsel and he was found to be innocent on the charges.”

For Carroll, the moral of Gideon’s story is crystal clear and illuminates the thorny circumstances public defenders face today. “You can’t just rush the process and make it an assembly line to process people into jail. Someone’s got to be fighting the system and testing the prosecution’s theory of the case to make sure that the person whose liberty we’re taking away is indeed someone we need off the streets.”

Morning session begins in Department 33 of Superior Court in downtown Fresno. Veteran public defender Kathy Marousek is my tour guide as we walk through the crowded corridor to felony home court. With 78 cases on today’s calendar, it’s a typical caseload but not an especially heavy one. Judges often preside over a hundred cases a day. In an atmosphere of quiet efficiency, prosecutors and defense attorneys make preparations processing paperwork and computer records.

The subdued murmur of business conversation and light talk makes it seem like any other office work environment. Several men in red jail jumpsuits are led in from a door at the back of the room and sit, handcuffed and shackled, in the jury box waiting for the disposition of their cases. Other defendants, along with friends and family, await the arrival of the judge in the gallery.

Most cases on the calendar are small-time behavioral transgressions like possession of drugs or drug paraphernalia, parole violations, driving under the influence of alcohol or with a suspended driver’s license and resisting arrest. Others are charged with crimes ranging from petty theft and burglary to various kinds of interpersonal violence. The bulk of defendants are represented by a single attorney from the Office of the Public Defender, who typically works a 12-hour day, often spending all day in the courtroom and numerous weekends in the office catching up on the backlog of preparation work.

Before the judge enters, the public defender converses with several of his clients about what will transpire in their cases. Fresno County’s Courthouse is a large monolith filled with such rooms—one of several court facilities that dot central Fresno. Collectively, they make up a criminal justice factory incorporating the lives, livelihoods and fates of thousands of people along with a big chunk of the county’s budget.

“It is so busy. Every day you’re just keeping afloat,” Marousek observes, “You never feel fully prepared.” For another public defender, Kristin Maxwell with 170 felony cases piled up on her desk, it’s a “constant onslaught.” Being prepared is a big deal. The overwhelming caseloads make this problematic. Jim Lambe, a 27-year veteran of the OPD who works on major cases, acknowledges the protracted time required for an effective defense, “My clients have a right to a speedy trial, or they can have me, but they can’t have both.”

Public defenders must perform effectively, or they can get in trouble. Failure to properly investigate, or any other lapse, can result in a case being overturned on appeal. According to Marousek, appellate attorneys often claim ineffective assistance of counsel, which can be reported to the California Bar Association. Preliminary investigation of the facts in a case, done in a timely manner, is absolutely critical to any defense.

Currently, Lambe is handling 14 serious cases and estimates a year in jail waiting for disposition of a case is routine. One of his clients has been waiting for six years. With the severe budget cuts the Office of Public Defender has endured over the past five years, the ability to promptly investigate and prepare cases has suffered. To do a good job, Marousek says, “Expertise must be commanded on every aspect of every case. It takes hours and days of scouring for information.”

If they cannot bail out, clients must endure jail time while waiting for justice. Marousek points out that “Gideon v. Wainwright is still a developing concept and far from perfect.”

Many defendants are categorized by the justice system to be mentally disordered offenders. Public defender Scott Baly declares, “Mental illness is so closely related to crime.” A mental illness designation can include drug or alcohol addiction, bipolar disease or other behavioral disorders. For offenders who can afford it, there are rehabilitation programs and counseling or probation in lieu of prison sentences, but they’re expensive, costing up to $2,000 a month, and the few public beds that are available have a long waiting list.

Additional pressure on courtrooms results from the closure of justice courts in the county’s far-flung rural towns due to the lack of money from the state, meaning people have to drive from places like Coalinga, which is 70 miles away, to be processed in downtown Fresno.

Along with overworked attorneys and brimming courtrooms, active judges are also in short supply with retired judges and appointed commissioners hired to fill in as needed. The Honorable Jim Oppliger, a retired judge, is working today and invites us into his chamber during a lull in proceedings. He underscores much of what Marousek, Baly and other public defenders have been saying, “Judges get upset when attorneys are not prepared. The court system is in coping mode because of the understaffing.”

He says it’s a setback to their careers because “attorneys need practical training and just can’t learn if they are in the courtroom too much. Right now in this county, public defenders are overburdened and so is the District Attorney.” He emphasizes that preliminary tasks like research, interviewing witnesses and visiting the crime scene are extremely important to defendants receiving a fair trial.

All defendants are innocent until and unless proven guilty. It’s the bedrock principle of our system of justice. It even says so on the home page of the Fresno County District Attorney’s Web site. But that’s not the experience Cameron Perger had with the criminal justice system. To him, it seemed more like a frightening episode of The Twilight Zone. His case underscores a major complaint public defenders have about the practice and policy of the District Attorney’s Office: The DA presses overly hard on charges they cannot prove. In other words, prosecutors seem too eager to presume the guilt of a defendant rather than innocence.

Charged with felony domestic violence against Perger’s former girlfriend, the mechanical engineering major at Fresno State faced 15 years in prison for a crime he said he did not commit and of which a jury found him not guilty. After his arrest in October 2012 on that charge, the DA piled on two additional charges for an incident he had never been arrested for and about which he had never been contacted by law enforcement authorities.

During this time, his bail amount was increased twice and he paid it both times so as not to await disposition of the case behind bars. But when the bail amount was raised a third time in January 2013, he simply could not afford it and was remanded into custody. For the next five months, he was held in the Fresno County Jail in a cell with 80 people, an experience he characterizes as demeaning and damaging to his reputation, “It was miserable, uncomfortable, no privacy.”

Originally urged by his public defender, Beth Lee, to negotiate with the DA, he refused insisting that “I’m not going to admit to something I didn’t do, I’m not going to have a felony on my record. I’ve got goals, I’ve got ambitions. I’m not going to have my life screwed up because of something somebody said.”

He was willing to bargain for a fair and reasonable settlement just to put the matter behind him, and get on with his life and school studies. But the only deal the DA would make would still have sent Perger to prison for years with a felony on his record, which is no small matter. Felony convictions strip a person of important citizen rights and besmirch one’s reputation and ability to obtain employment.

Perger opted for a jury trial. During that ordeal, he declares that the DA based the prosecution case on withholding, concealing and disallowing information that would have lent credence to his defense. He confirms that the public defender “did what she could with what she had, but I wasn’t going to spend months in jail waiting for the inundated Public Defender’s Office to essentially prove my innocence.” His credibility was questioned without allowing him to submit testimony about the credibility of the accusation, although he says there were circumstances that would have justified skepticism over the charges.

Perger alleges that the prosecution’s case was built only on the testimony of the accuser: “They did everything to take credibility from me regardless of my guilt or innocence.” At no point, he says, was any physical evidence or direct proof presented to indicate harm done to the accuser. To expedite his defense, Cameron helped Lee by working on his own to write opening statements and witness questions. “Everything that had been provided in the case, I reviewed it thoroughly and did everything in my power, because I knew she was overworked and underpaid.”

Understandably bitter about his treatment, Cameron doesn’t understand why the DA was pressing this case so hard against him. “The prosecutor didn’t give a rat’s ass whether I was guilty or innocent, all he wanted to do, I’m assuming, was make me some sort of example or teach me some sort of lesson.”

After acquittal, he asked the District Attorney for an apology. Receiving none, he is taking legal action against Fresno County for unlawful detainment.

Perger’s takeaway from his “absolutely terrifying” encounter in the justice factory is that the District Attorney needs to “prosecute the people that they don’t have any doubt in their mind about the guilt or innocence and leave the questionable cases out of it, because it’s wrong to try to do that to somebody that really doesn’t deserve it.” It is a sentiment that resonates with public defenders as well as the general public.

*****

Vic Bedoian is an independent radio and print journalist working on environmental justice and natural resources issues in the San Joaquin Valley. Contact him at vicbedoian@gmail.com.