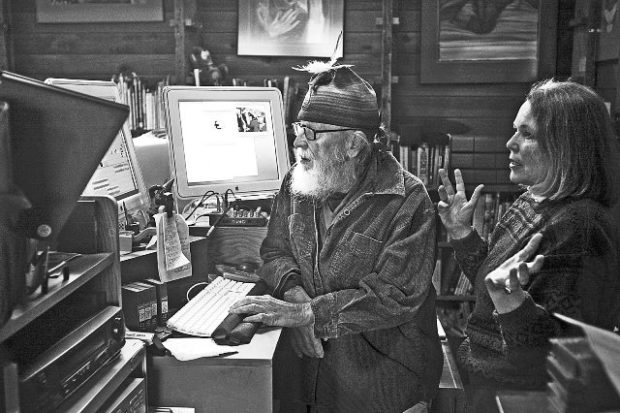

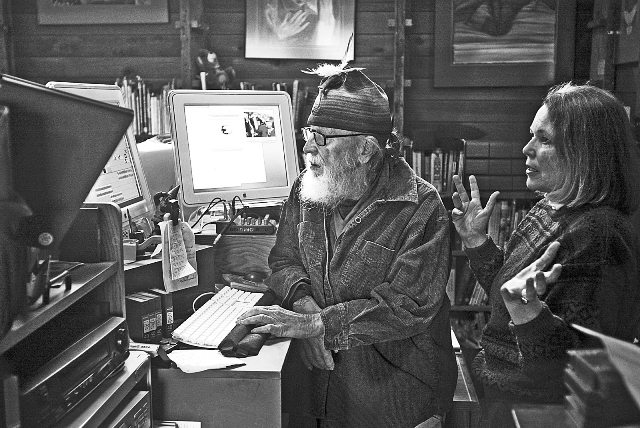

If you are a progressive political activist in Fresno, you have seen him with his video camera at your event. You may have watched his video docu-poems edited by him and his wife, Maia, at the SunMt film festival; caught a glimpse of their work on Channel 49, Free Speech TV or IndyMedia; or even visited SunMt’s 1,200+ page Web site www.sunmt.org. George (Elfie) Ballis and Maia Ballis are recognizable figures in the community, their work and reputation traveling way beyond the Central Valley. In 1991, Maia was named by the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom (WILPF) as one of “20 Fresno Women committed to Change.” In 1997, the Fresno Bee in its 75th year anniversary edition picked Elfie as one of “75 who made a difference.” His quintessential farmworker march photo was the article header.

His father named him George, but the “Elfie” name he now prefers came from Chris Welch of KPFA. She called his playful style of talking and dealing with heavy issues “elfin” during several interviews with him on her KPFA morning show. Ballis says, “Early on I was a George, a warrior. Now I’m an Elfie, a dancer.”

Elfie has a long history in photojournalism beginning on the streets of Chicago in 1951. In 1953, Ballis escaped his wire editor job at the Wall Street Journal in San Francisco to become editor of the Valley Labor Citizen (VLC), the publication of the Fresno, Madera, Kings and Tulare Central Labor Council (CLC). He was the editor until 1966 when a dispute arose over the paper’s support of Cesar Chavez and the United Farm Worker movement. The local liberal union leaders supported Elfie through his editorial unkindnesses to Jimmy Hoffa, George Meany and the then racist building trades unions, but they balked when their paper printed big-time support for La Huelga. Elfie resigned just before he would have been fired. The publication folded soon after and remained dormant for more than 20 years. (In an interesting twist of fate, the CLC publication was resurrected in 2000 when John Veen, then the editor of the Community Alliance, left this publication and became the editor of the new Valley Labor Citizen. But that is another story.)

Rather than get a pay raise at VLC, Ballis was able to reduce his hours so he could focus some of his seemingly boundless energies on civil rights in the South, and on social change and environmental issues, from local to national. He was mentored in photography by Dorothea Lange and on western water issues by Paul Taylor. He became a freelance photographer, joining the American Society of Magazine Photographers (ASMP).

In the mid-1950s, Ballis started chronicling the lives of farmworkers and the United Farm Worker union in the Central Valley. His pictures are unique because he was a part of the lives of farmworkers and the movement to build the union. He was not seen, and did not see himself, as an outsider trying to get a few pictures of these hard workers who put food on the nation’s table. His relationship to the farmworker movement was one of mutual respect and admiration. Elfie views himself as an advocate—not a documentarian or a “news” person. Today, you will see Elfie’s pictures of farmworkers enshrined in monuments, posters and most books and films honoring Cesar Chavez and the United Farm Worker movement. Elfie views the farmworker movement “as a natural for me. My photographic passions are focused on people, organizing and Big Mama (the Earth), issues all wrapped up in the farmworker movement. At 15, I began my work career in the fields pollinating corn for new hybrids for a Minnesota seed company. In the late ’60s, I was a part-time organizer for a farmworker union that preceded the United Farm Workers union.”

In 1962–1963, as president of the Fresno Democratic Association, Elfie organized the club into the second largest Democratic club in California—a broad coalition of liberals, seniors, veterans, unionists and professors. He used one-on-one organizing and lively, entertaining meetings on current issues to generate interest.

In 1963–1964, Elfie photographed and researched with the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) in the Mississippi civil rights movement. In the summer of 1964, he traveled from Mississippi to the Democratic National Convention in Atlantic City with the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party delegates. He photographed these democratically elected delegates who were not seated via a sellout by Walter Reuther, Martin Luther King and Hubert Humphrey.

In 1968, Ballis and Ed Dutton did a class on the power structure of the Central Valley at Fresno State with Elfie’s one “obscene picture” of the corporate ag land domination of the Central Valley. In the late 1960s into the 1970s, Elfie led community organizing workshops throughout the Southwest, including at UC Davis and Fresno State, always emphasizing grassroots people power. When folks tried to pin down his favorite political -ism, he would counter, “I’m a disjointed incrementalist—seeing any opening in any situation to expand people power.”

In 1967, Elfie was photographing the building of a self-help housing project in Kingsburg when he first saw Maia. At the time, she was a multimedia specialist working for a migrant education program and had volunteered to use her interior design background to advise the new homeowners on paint colors. At the end of the day, Maia in a green Sprite and Elfie in a red Sprite found themselves side by side. Elfie smiled, “Lady, do you want to drag?” She didn’t. She thought he was a wild man. “She was right,” Elfie brags. “But that is my essential charm.” “Charm?” Maia retorts. “His wildness is the price of admission. Of course, it’s worth it.” This opening flirt flowered into an ongoing 36-year partnership in passionate social activism. In a seven-day-a-week, 18-hour-a-day collaboration, they blend their skills in multimedia (film/photography, fine art, design, computer graphics, writing and editing) with continuing research and experiments in a green lifestyle.

Their first significant joint project was the 1969 production of a 16mm color film with El Teatro Campesino: I Am Joaquin. This 20-minute film-poem of Chicano history was an instant pri-zewinner and is still widely used in college ethnic study classes across the country. They went on to produce other films:

The Oakland Five. Blacks struggling with an oppressive Oakland school board. The Dispossessed. Pit River Indians trying to reclaim their tribal lands from PG&E, the Los Angeles Times, Southern Pacific Railroad and the San Francisco Examiner. Ballis helped the tribal elders do the ownership research and organizing, then filmed the action. He knew he was accepted by the tribe when a woman elder starting calling him “Chief Golden Hair.” Toughest Game in Town. Poor Chicanos in Santa Fe, New Mexico, organizing for political and economic power. The Richest Land. The glory and shame of California agriculture.

In 1970, for Jim Hightower’s Corporate Responsibility Project, Maia and Elfie charted all the boards that the Del Monte Corporation’s Board of Directors also sat on. It was a graphic illustration of the broad, intertwined jungle of corporate interests, and it was used to support regulating legislation.

Maia and Elfie also produced several important photo books on community organizing, most notably Visit Oakland the Friendly City: The Politics of Poverty in Oakland. In 1980–1981, Elfie was national president of Rural America, a Washington, D.C.–based advocacy group for rural community groups across the country.

In 1974, they began full-time organizing on land-water issues.

It was during the struggle against the large landowners on the west side that I first meet Elfie and Maia. At the time, in addition to working on National Land for People (NLP), they were instrumental in establishing Our Store (1975), a food coop in Fresno. We had no by-laws, no officers, no paid employees. Simple, direct, people-controlled democracy. Our Store, which was located at Echo and Weldon (across from Fresno High School) not only sold organic food in bulk but also created a sense of community. It was a meeting place and somewhere that people could learn more about peace and social and economic justice.

One of the NLP’s education tools was to take people on a “reality tour” of the Central Valley. People would come from all over the state to learn about the political and social reality of the Central Valley. Elfie would be the tour guide as the bus would take people out to the west side where they would see huge tracts of land that were made valuable at the taxpayers’ expense. The bus would then visit an organic farm run as a cooperative to show what the alternative to corporate welfare and large agribusiness operations would look like. After that, the tour would visit Our Store to illustrate what an alternative food distribution network looks like. It was visceral education in eating as a political act, as Elfie called it.

From 1956 through 1982, Ballis with Berge Bulbulian and a band of small farmers carried forth an epic struggle for small farmers’ water rights in Fresno’s Westlands Water District and throughout all the federally irrigated western states. The 1902 law had never been enforced anywhere. In 1975, the NLP was formally incorporated as a community-based political group for lobbying with a separate nonprofit corporation (501(c)3) to raise funds for public education and court cases to hold large farmers accountable for the water they received in the Westlands Water District through the publicly financed California Aqueduct.

In 1977, NLP moved its offices to a six-acre organic farm, the Magical Pear Tree, west of Fresno, after its downtown offices were burglarized twice by the Biggies’ agents. The Biggies also tapped NLP’s phones, did a make on Elfie’s life back to two days before conception and even pressured Wells Fargo to get copies of NLP’s monthly bank statements.

Farmers paid only 5% of the water’s actual cost, which enriched large landowners like Southern Pacific Railroad and Standard Oil. The federal law required that large (Biggie) landowners had to sign contracts agreeing that after 10 years of subsidized use, they would have to sell all land in excess of 160 acres at dry land prices (cheap) to new farmers. The Ballises with a small staff and board did research, educated the public and took litigation to the Supreme Court level to try to enforce the law.

The Biggies avoided honoring their contracts any way they could. One way they avoided the intent of the law—but complied with the letter of the law—was to break up large holdings into 160-acre lots by giving relatives, friends and employees (on paper only) 160 acres that they never saw or farmed. Some did not even know they “owned” the land when contacted by the NLP.

When the NLP won support in the courts to force large owners to live up to the spirit of the law, the large growers screamed violation of private property rights and threw enough money to lobbyists and contributions to the right Congressional campaigns to rewrite the Reclamation Law. In the end, the NLP won the battle in the courts but lost the war in the media and Congress. When big business interests want something badly enough, they simply change the rules of the game.

The spiral strategy of the NLP was that “we must grow a social structure which will actively support many people owning subsidized agricultural land.” At its small farm, in addition to the water fight, the NLP staff did organic-farming demonstrations with the federal Office for Alternative Energy directed by John Ballis. In addition, Marc Lasher organized a farmers’ marketing co-op, direct marketing maps and farmers’ markets, and George, Marc and Maia helped organize and sustain Our Store.

Administrative-organizing staff included at various times Gloria Hernandez, Lupe Ortiz, Jessie de la Cruz, Barbara Perzigian, Chuck Gardiner, Ann Williamson, Jim Ekland, Dave Heavyside, David Nesmith, Donna Martin, Ray Hemenes, Geneva Gillard, Vicki Sorter and Lang Russell.

The NLP got foundation grants for several years. When it had money, everyone—including Elfie as coordinator—was paid the same salary: $800 monthly. In 1980, as the farm was taken into the City of Fresno, the NLP lobbied city and county officials to support its organic farm in the city. The NLP was told to pack, so the NLP sold to subdivider John Bonadelle and moved to 40 acres near Tollhouse.

The NLP converted the new property to a land trust called SunMt, a 501(c)3 corporation supported entirely by memberships, donations and sales of products and services.

They designed and built a green building run primarily with solar energy, with a trial composting toilet for Fresno County, a gray-water system and many energy-conservation devices to demonstrate how people can live more simply and in harmony with “Big Mama.” A virtual SunHouse tour is available on the Web at www.sunmt.org/embracing.html. SunMt has been working on the design of the first straw-bale building in Fresno County for several years now. This green building system could reduce air pollution from the burning of ag-waste straw, which is a superior insulating material.

SunMt focuses on both community and individual responsibility. “We must walk our talk,” Maia and Elfie say. “We must not only demand good work from the Bushes and the Clintons. We must look in our mirrors and demand of ourselves lives of peace, justice and ecological sensibility in matters over which we have control—like our food, transportation and clothes. Example: If we all used solar ovens in this land of the sun, energy use in this area would plummet. Besides, living this way is all great fun. On sunny summer days, our PG&E meter runs backward because our solar electric system is generating so much power. Wow! We encourage ourselves and others to become the joyful peace and justice we seek. Living as best we can our personal and community lives the way we want the world to be.”

SunMt has published a CD of Maia and Elfie’s 30+ years of plant explorations: SunMt Herbal Cookery, an in-depth guide on how to harvest and use native and domestic plants for taste, health and fun. See it at www.sunmt.org/cookery.html. The spiritual core of SunMt revolves around “Monday morning shamanic medicine,” a homegrown update of the ancient ways. Elfie explains, “Every being, everything, is sacred. Connected. We can communicate with and learn from each other. The doorway is sacred ceremony using a world medicine drum in group, tribal gatherings. The beat of the drum, the heartbeat of the earth, awakens our cellular, tribal memories. For many more generations than we have been civilized, we were tribalized. Not just American Indians but all of us worldwide.

“SunMt restored that ancient way in us and in the many others who have come to share in and amplify this essential magic for greater peace, justice, and harmony.” From their medicine adventures, Elfie wrote and Maia illustrated a book called Rainbow Elf, Shamanic Visions for Our Monday Mornings.

Their return to motion pictures was a video that started out as a love letter from Elfie to Maia. The piece ended up as Elfie’s Eye, The Second Coming. A cinematic caress of SunMt. It won a 1999 Telly award, which Elfie says resembles an Academy Award statuette, “but it was delivered by a UPS guy, not an actress.”

Although SunMt is the focus of much of Elfie and Maia’s attention, most readers know them for their video docu-poems at local events. Elfie’s shot of Peace Fresno cop infiltrator Aaron Kilner made it into Michael Moore’s Fahrenheit 9/11. Many people are on the SunMt e-mail list and see almost instant coverage of local events in the progressive community. The video is almost like an alternative media.

View the Elfie-Maia video at www.sunmt.org/archives.html. Links from there will take you to many more details about the work at SunMt, as well as some interesting information about Elfie’s earlier life as a Marine in the Pacific Islands during World War II. He joined up at 18 in 1943. Elfie recalls: “The Marines kept their promise. They made a man out of me. Only it was not the man they had in mind.”

Elfie and Maia dance their media and organizing skills in a multitude of “different” issues across the ethnic face of America. They use the word we in all their work. “Seems quite natural for us,” Elfie says. “We all are one people whose lives affect each other. There is no them. Only us. All the seemingly different issues boil down to one word: respect. Respect for life. For each other. For all our relations—all beings animate and inanimate.”

To receive updates directly from SunMt, send an e-mail saying you would like to be on the e-mail network to mail@sunmt.org.