By George B. Kauffman

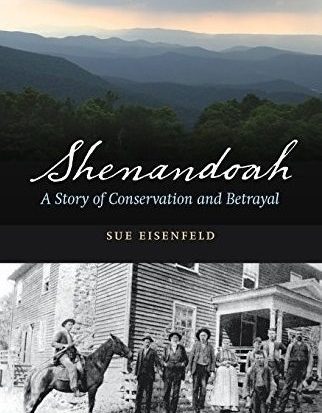

Shenandoah: A Story of Conservation and Betrayal by Sue Eisenfeld. University of Nebraska Press, $19.95 (paperback).

Award-winning writer, hiker and history lover Sue Eisenfeld grew up in my hometown of Philadelphia but has spent more than half her life in Virginia, where she resides with her husband, Neil Heinekamp, in Arlington. She studied natural resources at Cornell University and spent more than 20 years as a consultant in environmental policy and communications to assist federal agencies in Washington, D.C. She received her master of arts in writing degree from Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, where she is now a faculty member in both the M.A. in writing and M.A. in science writing programs. She has also taught at the Writers Center and is a consultant with ICF International.

Eisenfeld has written about history, hiking, nature, culture, life, food, health, medicine, Civil War history, weather catastrophes, personal friendships and travel journeys. Her writings have appeared in the New York Times, the Washington Post, the Washingtonian, the Gettysburg Review, the Potomac Review, Still: The Journal, the Blue Lyra Review, Hunger Mountain, Virginia Living, Blue Ridge Country and other publications. She is a three-time fellow at the Virginia Center for the Creative Arts. Her essays have been listed among the notable essays of the year in The Best American Essays (2009, 2010, 2013).

Eisenfeld hiked in Shenandoah National Park in Virginia’s Blue Ridge Mountains for 15 years. Like many others, she was completely unaware of the disastrous history behind the park’s creation. In this deeply personal travel saga, she tells of her discovery of the relics and memories that several thousand of the mountain residents abandoned when the government used eminent domain to expropriate private property for public use with payment of compensation and remove people from their land to create the park.

With maps and notes from previous hikers, Eisenfeld and her husband hiked, backpacked and bushwhacked the land, seeking stories. The descendants recount memories of their ancestors “grieving themselves to death,” speaking of their people’s displacement from the land as an untold national tragedy.

Eisenfeld describes the turmoil of residents’ removal and the human face of the government officials supporting the park’s formation. In this conflict between conservation to benefit a nation and private land ownership, she examines her complicated personal relationship with the park. She heartrendingly portrays the people displaced when the Shenandoah National Park opened in 1935.

Eisenfeld assumed that the land had always been wilderness. However, in Virginia’s Shenandoah National Park, she encountered “an incongruous, well-maintained cemetery in the middle of the forest” and realized that the land had once been a community where people lived, worked and buried their dead. For the next two decades, she searched the park’s past. She describes a history of the conservation movement that created spectacular sites like Yosemite, Yellowstone and Shenandoah. Based on extensive interviews and archival sources, she relates stories of families whose homes and lives were threatened by the government’s “good intentions.”

The Shenandoah project began with a 1926 Congressional act, mandating the government to create a national park in Virginia—convenient for the increasing mid-Atlantic population—by gaining title from landowners. Part of the act required that the government would not buy any land; it expected donations. Lawmakers enacting the bill assumed that the region’s few inhabitants, “the nameless and faceless mountaineers,” would not object to leaving “what many outsiders considered their godforsaken, hardscrabble homes.”

Eisenfeld acknowledges that Shenandoah and other national parks are “pockets of refuge in a country that is full of painful views.” She provides a detailed description of how this relatively young park was created at a great cost to the families who had lived there. A shameful 1930s propaganda campaign disparaged Shenandoah residents as uncivilized hillbillies. Some former residents were resettled in nearby communities, some were forcibly evicted and some were allowed to live out their lives at the park.

Th e S h e n a n d o a h National Park was based on intentional falsehoods. Ignoring the 15,000 people living within the originally proposed park boundaries, the original advocates claimed that the parkland was almost uninhabited. They claimed that the land was undeveloped, despite its long history of timber harvesting, mining and beef cattle production. Furthermore, they claimed that it was worth only a trifle of its actual value and therefore would be cheap to acquire.

However, the biggest lies involved vilifying the mountaineers who inhabited what was then known as Virginia’s “Great Mountains.” Families had lived and worked there since the 1700s, and flourishing communities dotted the landscape, but when they refused to vacate their land to satisfy a grand political vision, they were quickly labeled know-nothing sociopaths.

Families were paid as little as a dollar an acre for land worth 10 times as much. Virginia’s ruling political machine was confident that the new park would attract tourists, and it engineered a blanket condemnation. The land grab was spearheaded by wealthy businessperson William Carson, who stated that “there is no higher conception of duty than to feel we are of service to the State.” The government could have easily bought from willing sellers most of the land along the ridges and mountain crests where the Skyline Drive, the crown jewel of the park, was built. However, politicians wanted much more land on both sides of the mountain range.

Soon after taking office in 1933, President Franklin Roosevelt visited a Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) camp in the future Shenandoah National Park. Several years later, in an example of how FDR’s “freedom from fear” required giving federal agents unlimited power, CCC members were sent to burn down the homes of mountaineers who refused to vacate their land. The Hoover administration had promised that most residents would not be required to vacate, but the Roosevelt administration reneged.

The commandeering of 176,000 acres for the park provoked court battles that helped establish politicians’ right to seize private property for any purpose that they proclaimed. In the following decades, the same legal doctrines sanctified expelling more than a million urban residents from their homes. This dictatorial creation of the Shenandoah National Park is a warning that government cannot ravage property rights without ruining lives far and wide.

This not a new story, but it has occurred over and over since Europeans arrived on the shores of this continent. In national park history, it played out in that other great Appalachian park, Great Smoky Mountains National Park, along the Blue Ridge Parkway, and elsewhere in the park system. It continues even today as inholdings are purchased.

*****

George B. Kauffman, Ph.D., chemistry professor emeritus at Fresno State and a Guggenheim Fellow, is a recipient of the American Chemical Society’s George C. Pimentel Award in Chemical Education, the Helen M. Free Award for Public Outreach and the Award for Research at an Undergraduate Institution, as well as numerous domestic and international honors. In 2002 and 2011, he was appointed a Fellow of the American Association for the Advancement of Science and the American Chemical Society, respectively.