By Vic Bedoian

Virtually every aspect of life in the San Joaquin Valley will be dramatically affected by climate change. Mostly because of a warming planet. At a symposium sponsored by the Fresno Council of Governments, experts from UC Merced and state agencies briefed officials on the wide-ranging impacts to be expected. They were reacting to California’s Fourth Climate Assessment, which was issued in the fall. Since its last assessment in 2012, the state has experienced several of the most extreme climate-related natural events in its history.

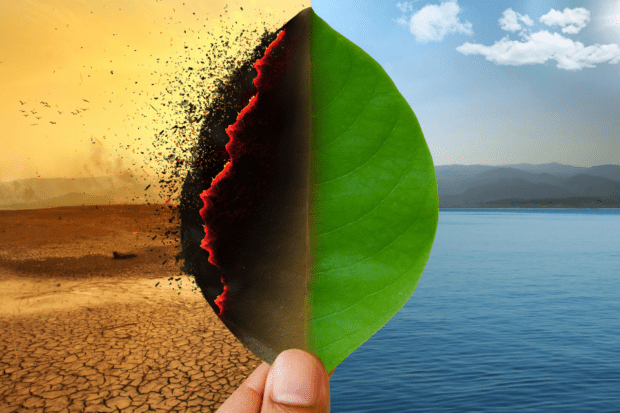

California is one of the most climate-challenged regions of North America; with a historically extremely variable climate, and climate change is making extreme conditions more frequent, while precipitation continues to be more variable.

Unlike the Trump administration’s climate change denial, many, but not all, Central Valley leaders are taking the study’s stark conclusions seriously. One of those conclusions is that the San Joaquin Valley’s environment and economy will be dramatically affected by the end of the century.

Joshua Viers is a professor of engineering at UC Merced focusing on water issues.

“Every indication is that it will be much warmer in California as a whole and certainly much warmer in the San Joaquin Valley,” he said. “We’re talking about four to six degrees Fahrenheit on average. This means that the minimum temperatures will be much warmer and the maximum temperatures in fact will be quite a bit warmer, and there will be more days greater than 90 degrees Fahrenheit, upwards of 30 days by the end of the century.”

The climate assessment found that, statewide, average daily high temperatures could rise by as much as 8.8 degrees Fahrenheit by the end of the century. For Fresno, that could mean 43 more days with highs exceeding 106 degrees. By 2050, average water supply from snowpack is projected to decline by two-thirds.

UC Merced Professor Josue Medellin-Azuara says that will seriously affect the Valley’s agricultural economy. “Reductions in irrigated crop area are inevitable due to the needed reductions in consumptive water use that are needed to balance the groundwater basins. So that will be more challenging than the potential reductions in climate change only,” said Medellin-Azuara.

He also concludes that Valley farmers could be growing different types of crops in the future to compensate for the loss of water resources.

“There are changes in technology that could change the varieties that are grown so that they can adapt to those incremental effects of warming. I think much important is the impact of groundwater regulations because that will limit the amount of groundwater that can be pumped during dry years,” he said.

California is a globally ranked biodiversity hotspot: Only 25 regions in the world have as many species. These species live in the state’s natural vegetation types: forests, chaparral, riparian areas, riverside and wetlands, as well as in its working landscapes, which include rangelands and agricultural lands.

Under current emission levels, 45%–56% of the natural vegetation in California becomes climatically stressed by 2100. The recent tree die-off during the drought of 2012–2016 shows how projected impacts already are having drastic effects.

The warming climate in the San Joaquin Valley will be compounded by wildly varying weather patterns. Viers says that will present major challenges for the health and economic well-being of the region’s population.

“Not only will it be much warmer, but precipitation is anticipated. On average the extremes of precipitation are likely to be much more pronounced. So we’ll have periods of prolonged dry periods, droughts much like that of 2011 to 2016, as well as very wet periods such as the one we had in 2017,” he said. “We’re starting to refer to this as the whiplash effect where we have the prolonged dry and the pronounced wet. Daniel Swain at UCLA as well as others have shown that the increased frequency of that will probably be twice as often. So being able to manage for those extremes is going to be a challenge for our infrastructure and our institutions,” Viers said.

Other factors, such as wildfires and rising sea levels, are expected to complicate matters even more. Climate change models predict that by 2100 the state could experience wildfires that burn up to 178% more acres per year than current averages. That, by itself, will significantly influence the future water supply for the Valley, as well as for the rest of California. Every aspect of life our lives will be affected: energy production, transportation infrastructures, farms, forests, rangelands and even the chemistry of the Pacific Ocean.

“California and the world need to rapidly reduce climate pollution to avoid the worst effects of climate change. We must also prepare for the continued acceleration of climate impacts in the future.”

That stark warning is even more sobering for those of us living in the already climate change impacted San Joaquin Valley.

*****

Vic Bedoian is an independent radio and print journalist working on environmental justice and natural resources issues in the San Joaquin Valley. Contact him at vicbedoian@gmail.com.