By Cecile Lusby

In late 1954 Mama was unemployed for a few weeks; The Cudahy slaughterhouse, her former employer, was now closed and shuttered. She found work as a bookkeeper at Roos Brothers in downtown Fresno. She drove my brother Steve and me to St. John’s School a few blocks from her new job. Every workday we drove back and forth six miles from Grandpa’s house by way of South Fruit Avenue.

Returning home, just outside the city limits as we approached North or Church Avenue, the smell suddenly changed. This was Fresno’s city dump for decades, a massive crater with its own special stench. The slaughterhouses further out in the county used to smell like cattle dung, but this smell was ripe, rotting garbage.

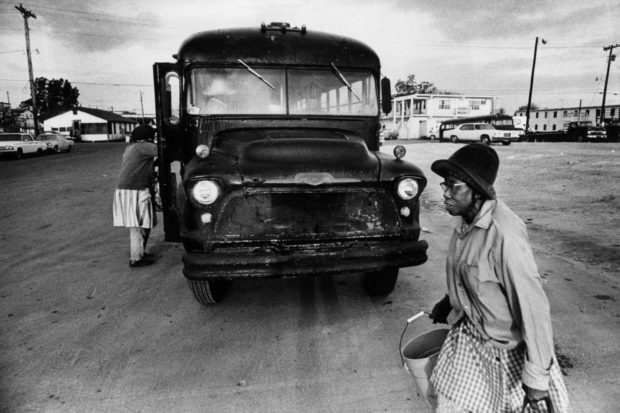

Right across the street from the dump were tarpaper shacks built for black farm workers, relocated from the South after WWII. In the thick fog of winter, the men huddled around fires in fifty-gallon drums. Old battered buses parked in the driveway to carry the laborers to their work sites, picking them up after daybreak and returning them home by evening.

No one in town saw these buses or their dark, sad-faced riders, yet it was an everyday sight in the country. I felt so sorry for them that I hunched down in the car so I would not have to meet their gaze. I tried to imagine waking up and getting dressed in those shacks and wondered where they could wash up. I wondered how they lived with that odor day after day.

The contrasts and the separation between the rich and poor bothered me. I went to public schools that were integrated, but I didn’t see colored people at St. John’s or at the other parishes in Fresno – not in class or in church. No one had ever told me that my church practiced segregation outside the South.

When I was in the eighth grade I asked Sr. Jean Frances about it privately and she told me Negroes had their own church, St. Peter Claver in a tiny black district on North Avenue just beyond the old Cudahy plant. It was closed six days a week, but every Sunday the Blessed Sacrament Sisters drove out to the area, picking up folks in their old station wagon to go to Mass.

I called the number and asked if they would take me along to St. Peter Claver. They dropped me off early and then left again to get more riders. My non-Catholic mother slept in after a six-day workweek; my brother sometimes slept late, too. My friend Catherine attended with her parents and six siblings, making us the only white people there, except for the sisters.

Catherine’s father, the son of German immigrants, was a gardener and a yard man who wore a clean pair of overalls and a spotless white shirt to church, her mom, a flowered house dress. Years later I realized that people at Catholic churches in town did not dress that way. Without my extended family’s support, however, I would have looked like Catherine’s family.

Since it was closed during the week, St. Peter Claver had no regular caretaker, so I brought greens at Christmastime and roses in May to make the bleak altar a little cheerier. I had no idea what else I could do to help. The sisters started to let me inside early to sweep and check that the bathroom was in good order. They would usher everyone in just before the services began; when it was cold they would turn the heater on and during the summer heat, we had an electric fan. Sometimes there were snacks for the children.

If we were lucky, one of the nuns would play the pump organ, which wheezed through “Holy, Holy, Holy,” “Sacred Heart of Jesus,” or “Little Flower of Carmel.” What a test of faith it must have been for our congregation when the Pentecostals in the Quonset hut next door started singing with just one tambourine in the whole church.

“At least they have fun,” my brother Steve said. Theirs was spirited gospel music with only the beat of their clapping. It was a treat for those of us next door since we had no rhythm at all and every word the priest said was in Latin, except the Gospel or, during the season, Christmas carols. I guessed the others came to church for Holy Communion. That’s why I was there.

It is worth noting that these two churches, Protestant and Catholic, stood side by side to serve the whole neighborhood; both churches – three blocks from the dump. To leave the Fresno city limits for South Fruit Avenue, you needed to pass two bars: The Snake Road Hut for whites, and the Jericho Café for black customers remembered later by Fresno’s jazz historians and police alike as a juke joint for blues and drug lovers of all colors.

Snake Road was the treeless, dusty end of the line for the Fresno Street bus and my brother and I waited at Snake Road Hut for Mama to pick us up after work. While waiting we listened to the jukebox and voted for Miss Rheingold. I asked Mama what the sign meant: “We reserve the right to refuse service to anyone.”

“Maybe it’s so nobody serves drunks more liquor to make them any drunker,” Mama said, never explaining its other intention to refuse service to blacks.

Fifty-five years later I tried to do research on that little mission, and there was not a word online. I called several churches and the Archdiocese where they found an article in a Catholic newspaper, The Register, referring to the fact that the chapel had been trucked in from a military base in December 1947 after serving Catholic soldiers during the Second World War.

Priests from St. Alphonsus Church drove out to serve Mass and the Sisters of the Blessed Sacrament for Indians and Colored picked up those who needed rides. These nuns were the religious order founded in 1884 by Katherine Drexel, (now Saint Katherine Drexel) dedicated to serving those two communities when segregation was practiced even outside the South.

As the Civil Rights Era progressed, the Roman Catholic hierarchy began to change the complexion of its congregations to blend in some color. The goal of integration in the pews and at the communion rails was imposed on Catholics from above, whether they liked it or not. In the first years, many segregationist Catholics stayed home or refused to go kneel at the rail for communion. The bishops held their ground and threatened those who refused with excommunication.

By the late 1950s, the clergy saw the cost of segregation as too high, counting extra little chapels and extra priests and nuns needed to help those faithful shunned by white Catholics. On December 28, 1958, right after Christmas, St. Peter Claver closed its doors forever, ending a long Catholic tradition of going along with the customs of its society, ushering in rebel priests like Fr. James Groppi or Frs. Phil and Tom Berrigan who fought to extend acceptance to all citizens.

In 1957 my mother, brother, and I moved into town and attended the church near us, St. Theresa’s, but something was missing. I noticed what my mother had pointed out earlier: immigrant women who knew neither English nor Latin said their rosaries instead of paying attention to the mass. I went to a tiny room off the altar with few people, few distractions. By summer I had stopped going to church altogether due to my anger over the forbidden book list.

In spring 1958 my mother and her boyfriend got married and we moved to San Francisco. In 1959 they bought a house in Mill Valley. My mother was moving up. I signed up to participate in the Fair Play for Marin Housing and started to pass around a petition to end the restrictive racial covenants. My mother put a stop to that, and so I began to focus on my political beliefs rather than on religion. I lost one faith and acquired another.

St. Peter Claver stood from Christmas 1947 to Christmas 1958 filling a need to serve the souls on the wrong side of town. I think the Pentecostals used the mission building for awhile. When my mother and I drove by in the 1980s, the chapel was gone. It exists now only in memory, and there is precious little information about the decades when Black Catholics did not just sit in the back rows of a church but had to go to separate little missions, even in California.

Time passed. The shacks and tents disappeared by the late 1960s, their old residents moved on. The departure of the farm workers was the last barrier to the official conversion of the area from mixed residential to industrial use. Soon tractors and backhoes scrambled up and down the road, filling in the noxious cavity of the South Fruit Avenue dump.

Months of dirt deposits tamped down by tractors led to the final step in the construction of today’s Hyde Park Mound: an exhaust pipe coming up to the surface to release the methane emissions from the rot at the base of the old dump lights a flame in a park without benches. One might hope the flame has died out by now.

The legacy of redlining and polluting the water and air of nearby poor neighborhoods continues. South Fruit Avenue as it crosses Church and North Avenues is the current route to several meat and poultry processors and the Darling Rendering Plant a couple of blocks away, so the residents of Southwest Fresno still live with air pollution from the meat and poultry packing plants emitting the constant odor of blood and guts, hides and feathers. The more things change…

*****

After a childhood in Fresno and early marriage in Berkeley, her mature life began with divorce and single motherhood, finishing her education in midlife. Lusby earned her credentials as an English teacher and a school counselor working with teenage foster youth in San Mateo County. Now retired, she lives in Sonoma County where she volunteers for the Interchurch Pantry of Sebastopol and contributes to the Sonoma County Gazette and the Independent Coast Review. Her website is cecilelusby.com. Read her previous article on Fresno in the 1950’s in Community Alliance newspaper at https://fresnoalliance.com/the-way-to-town/