By Richard Stone

(Author’s note: While in Fresno to speak at the Progressives’ gathering on Oct. 1, Jim Hightower graciously afforded the Community Alliance time to interview him one-on-one. In the absence of our vacationing editor, that opportunity came to me.)

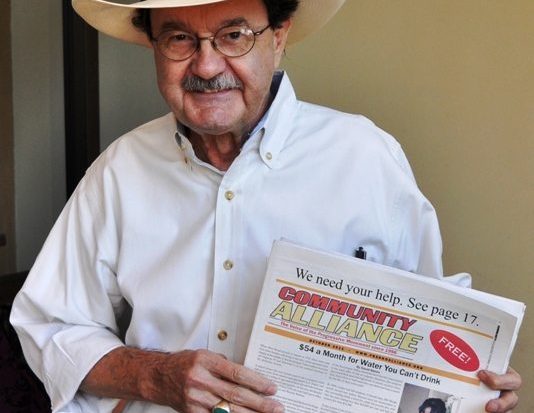

Jim Hightower close-up is pretty much like Jim Hightower the public speaker—modest, congenial, witty, knowledgeable and dedicated to the proposition that democracy works when power is dispersed. He believes in, trusts and likes “the little guys.” For his visit to Fresno, his requests were for non-corporate-owned accommodations (the organizers couldn’t find any!), a location where he could walk and mingle, and locally brewed beer in the fridge. Not your typical celebrity wish list.

At his request, I met Hightower at a “watering hole” near his hotel, where we sat out back as he sipped a beer. I was especially curious about how a small-town Texas boy grew up to have the political perspective he has—radically egalitarian and anti-corporate. His answer was a brief guided tour through the history of populism, which he distinguishes sharply from liberalism. “Liberals look to social programs to make things better, populists look to actions they can do themselves,” actions to get out from under the financial institutions and power structures that keep them down.

And populism, it turns out, is deep in the historic heart of Texas. “Texas was largely founded by refugees from foreclosures to the banks in the East. They were called GTT’ers: They left signs with those letters on their abandoned property, meaning ‘Gone to Texas.’”

Populism, he went on to explain, was an economic self-help movement starting with agricultural marketing and distribution co-ops to evade the hated middleman, but growing into a full-fledged social network that included educational and cultural programs. It began as the Farmers Alliance but blossomed into inclusive institutions embracing organized labor and even going across racial divides.

It was a true class conflict, the little guys standing up (for the most part nonviolently) to the bankers and railroad men who tried to run their lives. “For years,” Hightower informed me, “Texas had laws outlawing the formation of banks and requiring a two-thirds vote of the Legislature to establish a corporation.”

Speaking of his personal history, Hightower described his parents—though living well past the heyday of the Populist Party—as “instinctive populists.” His father was a small businessperson who spoke out often against the interference by large interests, and mistrust of “the system” was part of the family ethos.

During the early civil rights years, Hightower, though in a segregated school, found himself wondering about “who those other people are.” He chose to attend what is now called the University of North Texas, the state’s first integrated college, where he actually met Blacks for the first time. There, too, was where he began to learn about the history of populism in Texas, and he also participated in the antiwar movement of the 1960s.

After college, he worked for Ralph Yarborough, a progressive U.S. Senator who often supported organized labor against the petrochemical interests that dominated state politics. “One of Ralph’s favorite lines was, ‘You got to put the jam on the lower shelf so the little people can get to it’” Hightower recalls, his own literary roots showing.

Hightower began to become a known quantity when he took over editorship of the Texas Observer, succeeding the retiring Molly Ivins. “My first editorial in 1977 was that the symbol of Texas had changed from the oil derrick to the high-rise headquarters of the banks and corporations.” He’s kept on subject much of the past 30-odd years.

Readers of his newsletter The Hightower Lowdown, his books and articles know that much of his work is directed at revealing the covert influences of power and money, and debunking the beneficence of corporate capitalism. In a world where we are so immersed in the products and ideologies (including the need for “security” and militarism) of these big interests, how, I asked, do we begin to extricate ourselves?

Hightower offers no grand schemes. He begins with personal consumer choices—his requests for guest treatment being indicative. “Consume with moderation, shop local, buy American.” He likes farmers’ markets and brew pubs; he owns a high-mpg low-cost Ford Fiesta.

He is a big believer in co-ops and worker-owned enterprises. He says there are more than 73,000 co-ops in the United States, and his optimism about the possibilities of such enterprises is undergirded by the amazing successes of the 19th century Populists before they were destroyed by misplaced political trust (in the backing of William Jennings Bryan for president) and economic sabotage by big business.

He cites the story of Leland Stanford, the railroad tycoon who shed his corporate identity and founded Stanford University specifically to teach the principles of co-op economics. (Later, he lost control of his own project and it became the Stanford we know today, home of—among other things—the Hoover Institute, which shelters our very own Victor Davis Hanson.)

Hightower is a firm believer that entrepreneurship and democracy can coexist. As one example, he looks to what he terms “the food revolution” that has altered the food business over the past couple of decades as people have begun to demand flavor and nutrition; good treatment of land, animals, and workers; and smaller energy footprints from our food producers.

Are such remedies strong enough and timely enough to rescue us from the destructive forces unleashed by corporate capitalism? Can our ill-educated, misinformed populace be weaned from the comforts and conveniences offered us (like Esau’s mess of pottage) in exchange for giving over to imperial rule?

Hightower makes no pretense of knowing. He sees clearly what is wrong and who benefits from keeping it that way. And he knows for certain which side he’s on. He is inspired by a lineage of populists and opposers of power, people who have used humor and music and popular culture to raise questions and foster community. His circle of like-minded comrades includes activists like Ralph Nader and Norman Lear, Mark Twain and Molly Ivins, Woody Guthrie, Michael Moore and John Sayles.

Like these folks, Jim Hightower has the gift to invite people into a vision of human-scale enterprise filled with good humor, food, song, and caring… and a hearty disdain for wealth and power. He reminds us that the emperor is but a man, that we have our own minds to think with, that together we can do remarkable things. He’ll remind us that the man in the headlines “puts the goober in gubernatorial,” that Woody Guthrie wrote “This Land is Your Land” because he couldn’t stand Kate Smith’s “God Bless America” and that “the only things in the middle of the road are yellow lines and dead armadillos.”

Maybe such activity won’t save the world, but it’s a damn good way to make friends and act constructively until something better comes along.

*****

Richard Stone is on the boards of the Fresno Center for Nonviolence and the Community Alliance. Contact him at richard2662559@yahoo.com.

IDENTITY BOX

Name Jim Hightower

Birthplace Denison, Texas (a railroad town)

Ethnic background Heinz 57

Religious affiliation None

Political affiliation Progressive Democrat

Motto Agitate!

Non-political interests Sustainable Food Center (for farmers’ markets, food policy and music)

Unexpected interests Art museums (especially folk art) and having a variety of hats.