“I remember, as a child, three or four years old, going to funerals of men in Pixley, Arvin, Ducor, Visalia, throughout the Central Valley. These men had died alone, by themselves. I remember burying these guys, and I never knew how much that affected me.”

—Johnny Itliong, son of Filipino union leader Larry Itliong

On Sept. 8, 1965, the Delano Grape Strike was ignited in Delano when brave Filipino American farmworkers, members of the Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee (AWOC), led by community leader Larry Itliong, courageously walked off the vineyards to demand respect, better wages and improved working conditions. Itliong then convinced Cesar Chavez and the National Farmworkers Association (NFWA) to join the strike on Sept. 16, 1965, rather than cross the picket line. The strike lasted five years.

This historic strike marked the beginning of a powerful multiethnic coalition that changed the course of labor rights in the United States. The Delano Grape Strike became a turning point in American labor history, leading to the formation of the United Farm Workers (UFW) and sparking national attention to the exploitation of agricultural workers.

Life for Filipino Farmworkers in 1965

Filipino farmworkers described their life in the Delano grape fields as a cycle of extreme hardship and injustice marked by poor living conditions, low wages and discrimination. In the 1960s, although Filipinos were technically American nationals, they faced legal and social discrimination.

Anti-miscegenation laws prevented Filipinos (who were overwhelmingly young men) from marrying white women. Police raided Filipino dance halls, and violent mobs targeted Filipino communities. The only work available to most Filipinos was low-paid agricultural, cannery and domestic work.

They faced dangerous and exploitative conditions, with many suffering from chronic health conditions due to long hours, low pay, pesticide exposure and harsh practices in the fields. Many were employed in the grape fields throughout California in appalling working conditions, with both health and safety concerns, including limited access to healthcare, as major issues.

The life expectancy of a farmworker in the 1960s in California was just 49 years old. As elsewhere, Delano grape workers faced health and other major issues. Reaching a breaking point, more than a thousand Filipino farmworkers walked off the job on Sept. 8, 1965, in Delano, kicking off the years-long strike that finally concluded with successful collective bargaining agreements, increased pay, improved benefits and better working conditions for thousands of farmworkers.

Commemorating the Historic Strike

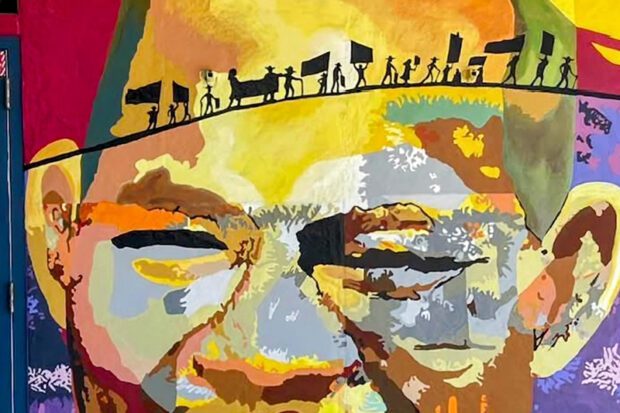

Delano’s 60th Grape Strike Anniversary, Sept. 8, 2025, organized by the Delano Chapter of the Filipino American National Historical Society, was a day-long event called “Bold Step 2025” held at Robert F. Kennedy High School.

Speakers included California Attorney General Rob Bonta; Dolores Huerta, founding member of the UFW; Lorraine Agtang, one of the few surviving first strikers from 1965; and Johnny Itliong, son of Larry Dulay Itliong, the legendary Delano farmworker leader who started the strike.

Filipino American union leaders, including Larry Itliong, Philip Vera Cruz, Pete Velasco and other members of the manongs (elder) generation, played a foundational, and often under-recognized and overlooked, role in organizing, sustaining and sacrificing for the farmworker movement.

One of the main goals of the anniversary event was to continue to remember and recognize the courage, leadership and legacy of Filipino American farmworkers and their contributions to the labor and civil rights movements here in California and across the United States.

In the packed high school auditorium, Bonta, the 34th attorney general of California who has served since 2021 and a lawyer and politician of Filipino and American descent, gracefully addressed the excited crowd: “It’s so important to mark this occasion and remember what it meant and what it continues to mean.”

Turning toward a fellow panelist, he continued, “I’m happy to acknowledge and pay my respect to the amazing, iconic, the one and only Dolores Huerta.” The audience honored the Latina legend with applause and gritos (shouting).

“The Delano Grape Strike of 1965 of the farmworker movement is more broadly, uniquely, a California story,” Bonta stressed. “It really reflects that phrase in California, about California, ‘As California goes, so goes the nation,’ and it represents the Californian exceptionalism that we are all so very proud of.”

“Courage and Resilience”

Bonta reminded the audience, “It shows courage and resilience. It shows fight and heart. It shows a desire to dream for something more, something better, something more fair—something more just and to take the risk and to go first, to make it happen.”

“To create change, to realize that you can’t just sit back and wait for change to happen. You need to be that agent of change,” he urged.

“You bring the change. Don’t look for the cavalry. Look to your left and right: You are the cavalry. If the change is going to happen,” Bonta said, “you’re going to have to make it happen.”

Bonta brought a much needed inspirational message of solidarity and resilience to the anniversary. “The courage of those who led the Delano Grape Strike of 1965 has never ceased to inspire and amaze me,” he said.

“It’s also a story that is rooted in the power of unity. What we can accomplish when we fight together, when we lock arms, when we look after each other, when we take care of one another and realize that we’re all in this together. That there is no ‘you versus me’ or ‘us versus them’—there’s only us.”

After Bonta’s remarks, Huerta shared a special memory of the farmworker meeting that voted to support the historic strike. Simply put, “We took a vote and all of the people said, ‘We gotta support the Filipino workers!’ and we did—we went on strike—we went on huelga!” she told the crowd to roaring applause and more gritos.

“The beautiful thing about it,” she continued, “we people were together. We merged two crews. No more separation. And you know what came out of the merging of the crews?” she joked, “A lot of marriages.”

“It was showing the world that people can work together,” she added. “Not just the Filipinos and the Mexicans—everybody worked together to make it happen.”

“That really shows the power of collective action,” she emphasized. “Again, I have to say to everybody here,” as she concluded her remarks to a standing ovation and excited applause, “Larry was a fearless leader.”

During an afternoon panel titled “Life in Delano Before, During and After the Strike,” Lorraine Agtang, who was only 13 when the walkouts began, said, “I was working in the fields [with my family] for one of the big growers that was against the union. [Striking workers] were saying ‘come on out, brothers and sisters, join us!’

“I was a kid, you know, working with my sisters, father and mother, so I said, ‘we’re leaving, come on!’” She added that the strike was her first experience with civil disobedience. “The strike made a big change. After the strike, people began relating to each other.”

Later in the event, Johnny Itliong, Larry’s son, echoed this same sentiment: “I am my father’s son, and my father’s focus when he first came out here was to help the Filipino people,” he explained.

“But ultimately, it turned into helping the poor. The poor don’t have a race, the poor don’t have a color, the poor don’t have politics. The poor are hungry, the poor need a place to live, a place to stay—water to drink,” he said with flowing tears.

“It’s over a hundred degrees out there,” Itliong painfully remembers. “Bathrooms—there were no bathrooms for us. There was just a hole in the ground. My dad did so much for so many people, and his legacy must continue.”

As we commemorate the success of the historic Delano Grape Strike of 1965, may we continue to stay united and stand in solidarity with California farmworkers today. It is incumbent on all of us to defend and come to the aid of California farmworkers in these troubling times.