By Tim Simmers

Every Day We Get More Illegal by Juan Felipe Herrera, City Lights Publishers, San Francisco, 2020, $10.47 paperback.

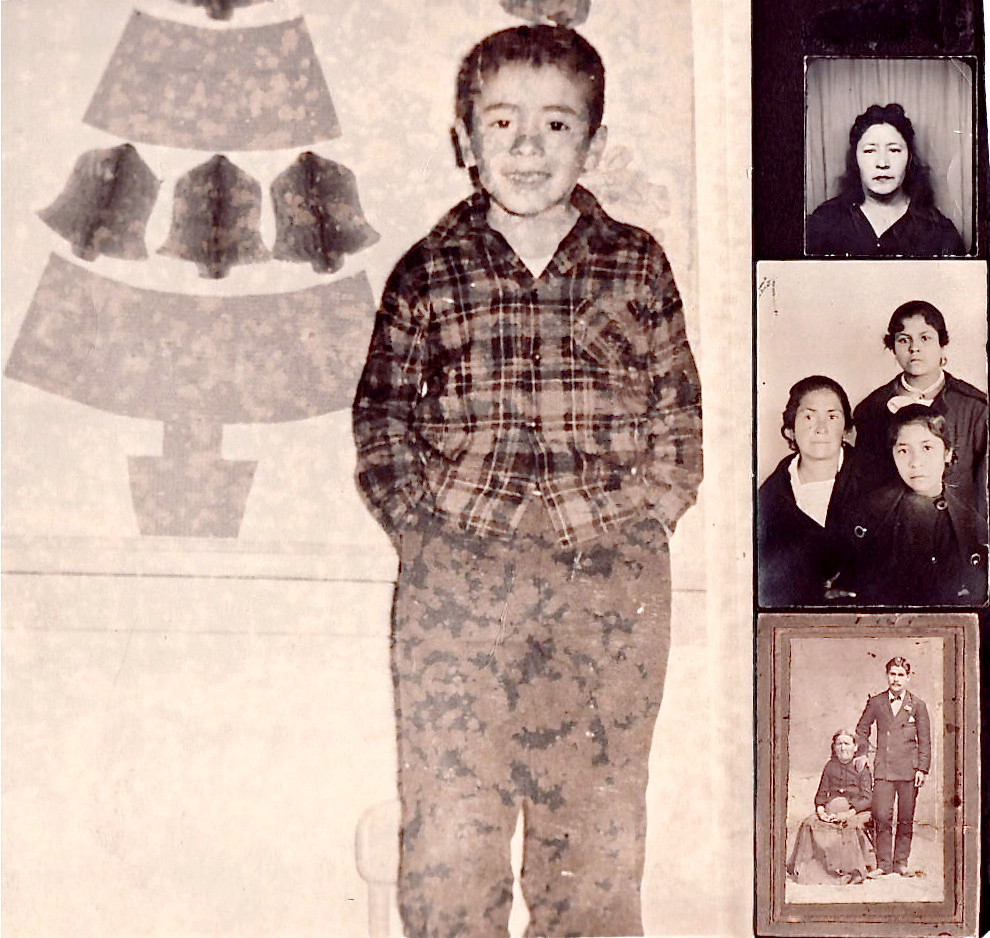

As a child of immigrant farmworkers who picked crops in the fields of the San Joaquin Valley and Southern California, Juan Felipe Herrera has a good feel for life as a migrant worker.

He moved around a lot, sometimes living in trailers and tents with his mother and father as they followed the harvest, so it’s no surprise his latest collection of poems, Every Day We Get More Illegal, has a clear ring of truth to it.

He wrote the poems like a letter to America, and it wasn’t an easy letter for him to write because he speaks directly about immigration, poverty and the exploitation of workers in tumultuous times, and he’s not holding back.

Born in 1948 in Fowler, just south of Fresno, it’s been a long road from the fields to becoming poet laureate of the United States (2015–2017). After two years of traveling in that standing through towns across America and listening to the aches and pains of the people he met, Herrera brings poems that draw a stark picture of this country.

The poems portray the struggle, suffering and pain of people pushed to the edge and stung by the separation and divisiveness of the borderline during Trump’s long presidential campaign and early months in the White House.

“He was a sponge for all this weight, and psychic energy and fear in the community going from town to town, and he honored those experiences,” said Fresno poet Anthony Cody, who calls Herrera a mentor.

Cody wasn’t surprised that Herrera shifted to a heavier, more serious tone in his latest poems “because he’s a listener, attuned to those around him.”

While pulling no punches in the book, Herrera also includes the spirit of peace, hope, humanity and the possibilities of unity and community, common themes in his work.

“I wrote in a direct manner, talking to the reader, to America, to the consciousness that wiggles in between us,” said Herrera, who lives in Fresno and is U.S. poet laureate emeritus at Fresno State. “I wanted to relate to people’s concerns in these times.”

In his powerful poem, “You Just Don’t Talk About It,” Herrera taps anger and emotion:

You prefer the holiday merchandise the national vacuum

You just don’t care about the pushed out the stopped out

The forced out the starved out the fenced out the shot down

The cut back the asphalted out on the other side of the track

The suicided the hanged w/a bedsheet

Of nothing in the cell of nothing

An ardent activist for immigrants and indigenous communities, Herrera started hearing poetry at an early age from his mother, Lucha Quintana Herrera. She went only to the third grade in school in El Paso, but she recited poems to him she memorized from school.

“She was always reciting poems to me since I was a child,” said the quick-witted and sage-like poet. “You could say she was training me to be a poet.”

Mama Lucha also played guitar and sang old narrative-style Mexican corridos to him. Herrera remembers the stories from those ballads and sometimes sang them with his mother.

In his youth, she encouraged him to “get a guitar, you’ll always have a companion.” Before long, he was playing the folk songs of Bob Dylan and Woody Guthrie, and was crazy about Joan Baez’s voice.

Herrera was the only child of his father’s “second family,” as he puts it. His father, Felipe Emilio Herrera, worked long hours and Juan learned a lot about play and imagination and drawing cartoons. He likes to play with words like a mad scientist who stirs chemicals together to see what happens.

“I get inspired and excited putting words together in one sentence that doesn’t seem to go together,” he wrote to a 12-year-old boy who wrote him about why he used words that didn’t go together—“like space and vegetables.” Herrera is a big advocate of children and ordinary people writing poetry and reading to one another.

Though he likes being playful, his recent collection of poems touches more on people crossing borders, whether they’re documented or undocumented, and about justice and culture.

In “Touch the Earth (once again),” he pays respect to workers—the washer-woman and the laundry workers, the grape and artichoke workers, the cucumber workers and many more. In the end, he urges readers:

Notice: where they cash their tiny & wrinkled checks and pay stubs;

Stand in that small-town desert sundries store, then walk out they do

& stall for a moment they do underneath this colossal tree

With its shedding solace for a second or two

Notice: how they touch the earth—for you

“I feel like I never got to this style—direct, right on the plate,” Herrera said.

In elementary school outside of Escondido, Herrera never talked in class and sat in the back row. He shut down speaking after a teacher took him over her knee and spanked him for being late in the first grade. He just sat back and observed until the third grade, when a friendly and kind part-time teacher, Lelya Sampson, asked him to come up in front of the class.

She knew he liked music and asked him to sing a song. He sang “Three Blind Mice.”

“You have a beautiful voice,” Sampson said for all the class to hear. Herrera walked back to his desk and tried to “unlock that phrase.” It haunted him at first, but eventually, it freed him after thinking about it. He later sang “Swing Low Sweet Chariot” at a school assembly.

“She gave me the magic keys,” Herrera said about his teacher. “Those five words changed my life.” They allowed him to give the magic keys to his own students who now see him as their mentor, a local treasure and a national poetry icon living among them.

“Dozens of people speak to him as their mentor, he’s been there for people,” said Cody, author of a collection of poems called Borderland Apocrypha.

When Herrera was U.S. poet laureate he invited Sampson when she was 95 to the Library of Congress inauguration. He told the story of her asking him to sing and what it meant to him, and then he introduced her to the audience. She received a rousing ovation.

Tim Hernandez, a creative writing professor at the University of Texas–El Paso and longtime Herrera friend, sees the new book as an extension of where “Juan Felipe has always been.”

“It’s very vast and expansive,” said Hernandez, who resided in Fresno for years and wrote the book All They Will Call You, based on Woody Guthrie’s lyrics in the song “Deportees.” “He takes small acts of daily life into a bigger picture of the universe, and he condenses complex ideas into the least amount of words.”

Herrera’s newest book, released before the November election, was published by City Lights Books in San Francisco. City Lights was founded by the late poet Lawrence Ferlinghetti, one of Herrera’s early influences, along with poet Allen Ginsberg.

The provocative title, Every Day We Get More Illegal, just came to him one day.

“There was always a new law or executive order,” he said. Changes in the citizenship exams, surprise new stops at the southern Mexico border, more detention centers and separating families. “There’s always more requirements and they pile up,” he said.

He remembers a young migrant boy he met in Jackson, Wyo., who told him: “I’m here, but I still feel like I’m in Mexico.” Herrera says “there are pain and suffering, and there’s overcoming and flourishing.” He embraces the possibilities of overcoming.

“We’re human beings, we can fall apart, but it’s all right. We can get up again,” he said.

Herrera has written more than a dozen collections of poetry, including Notes on the Assemblage, Senegal Taxi, 187 Reasons Mexicanos Can’t Cross the Border: Undocuments 1971–2007 and Half of the World in Light: New and Selected Poems, emphasizing his Chicano identity.

The nation’s first Latino poet laureate also has written books of prose for children, including Lejos/Far, Jabberwalking and Upside Down Boy.

He’s lived in many parts of California, such as San Diego, Riverside and San Francisco, where he went to elementary school for a while in his beloved Mission District. He was California’s poet laureate from 2012 to 2014.

In a recent playful moment, Herrera claimed the fruits and vegetables had their stories about farmworkers. As if they could hear the dialogue while the pickers picked. He believes he has those stories in him because his mother worked in the fields when she was pregnant with him.

*****

Tim Simmers is a freelance writer, teacher and longtime Bay Area journalist who moved to Fresno last year. Contact him at tsimmers11@gmail.com.