By Paul Thomas Jackson

According to Marx, capitalist society consists of two parts: the base and the superstructure. The base has the market forces and relations of production and property. All relationships in society are determined by the base, which gives rise to the superstructure (meaning the culture, institutions, political power structures, roles, rituals and state).

To Marxist observers, no time of the year is one aspect of the superstructure—consumer culture—plainly or painfully obvious as it is in Christmastime. The ad industry goes into hyper-drive, generating as much as 40% of annual sales by businesses.

“Toys” are no longer “Us,” but board games are still a great way to have facetime and fun. (Not to be confused with FaceTime that you use for all of your video calls.) Cell phones might be convenient for 300 million Americans. Yet the truth remains that face-to-face communication is efficient and informative. Indeed, to communicate with and understand one another, we gain 93% of our information nonverbally (according to Mary Ritchie Key of UC Irvine).

To its credit, Fresno Ag & Hardware, one of the city’s oldest retailers, carries a variety of low-tech toys and games for young children. (Full disclosure: The writer has no relationship to Fresno Ag and merely identifies it as a rare source of old-fashioned toys.) But among the board games that are for all ages, none has remained more popular over the years than Monopoly.

During the winter holidays in my early years, elders in our family would encourage us young ones to socialize while playing Monopoly and other board games. Lively interaction ensued at what came to be known as the game table and was almost always fun. Heading into our teen years, the emergence of our egos would create stumbling blocks in Monopoly, so our elders came to regulate our play of this game.

Holding our teenage egos in check, they’d remind us to always behave well with our cousins, not gloating too much with the acquisition of the fourth house or hotel, nor greeting the arrival of another player’s token with conceit. We “hoteliers” would go get that unlucky player a refill of hot cocoa or mint tea.

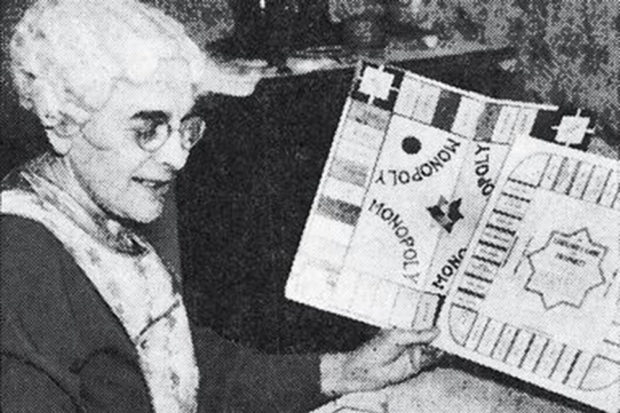

In retrospect, that experience of our family reminds me how, as I’d later learn as a PoliSci student, government came to regulate the economy for public safety in the late 19th century and for health, safety and the general welfare in the 20th. The game of Monopoly, as I would also learn, was created in 1903 by Elizabeth Magie, an exponent of Georgism. Called “The Landlord’s Game,” Magie’s invention led to the game we know today.

In the 19th century, Henry George was an enormously popular political economist and journalist. He believed a person should own the value s/he produces, but all members of society should equally share economic values derived from land, including rents and natural resources. Magie wanted to bring home the insights of this Progressive economist.

“We must make land common property,” wrote George. To do so, he proposed taxing land values, so society could recapture those values that it inherited, improve land use and raise wages. There would be no need to tax productive activity in George’s view. He believed the “single tax” on land would remove existing incentives toward land speculation and encourage development because landlords wouldn’t incur tax penalties for developing their land.

Nor could landlords profit by holding valuable sites vacant—a view particularly relevant to Fresno today, inasmuch as owners of land here, many of whom are in the Silicon Valley, sit on it until its value increases to make selling it a worthy return on their investment. None of that economic activity appears advantageous to Fresno residents.

Marx shared George’s concern for working people. But on public policy the two differed sharply, Marx regarding George’s “single tax” as a departure from the path to communism sought by Marx. George predicted Marx’s ideas would, if pursued, lead society to a dictatorship. History would prove this outcome at the instigation of Lenin, a generation after George’s passing and taking place in a country at a stage of development quite different from that envisioned by either George or Marx.

The game of Monopoly, on the other hand, is a simple yet effective way to understand George’s critique of the kind of capitalism in vogue, both in his time and now. No dictatorship per se, but the injustice of unchecked land speculation is the lesson we draw from the board game, tempting younger players to behave as smugly as speculators might in George’s day.

The existence of uninhabitable properties in a city, held by landowners having no loyalty to the city, is a continuing injury to us. The resulting sprawl is a headache to everyone, like a board game that’s emotionally exhausting if not fun. Poor people feel the crunch of the housing crisis, putting them at risk of homelessness. And the plight of people affected most directly by the economic “game” and the resulting housing crisis, the homeless, is rarely much fun.

The green houses and red hotels are all bought up, so that rents are unaffordable to people who are homeless or nearly so. It seems their dice rolls didn’t land them in lucky places, and their odds got far worse once they became homeless. If landing on “community chest,” they have to part ways with their animal and human companions, trusted allies, before they can receive aid from nonprofits.

Landing on Chance Avenue, a homeless person might receive aid to help meet his most basic needs. This decade, state lawmakers have passed many laws to curb the homelessness of families and veterans. For centuries, social workers have intervened in families who are at risk of homelessness, and county welfare departments and school districts strive to help them.

But, like the lonely token on the big game board, many single homeless people lack any particular place to call home. He slogs through his circumstance in our midst, moving about us winners of the awful economic game that we play against him, perhaps unaware, and possibly against ourselves. He’s cited for a petty offense and unable to manage his affairs to appear on the citation. Not able to jot down the court date in a handy place, he forgets it and must go to jail. There is no “get out of jail free” card.

After much toil without any promise for his efforts, a single homeless person might resign himself to his apparent fate. He may then discover a little pride in having proven his adaptability and survival skills. And so he might seem carefree to us, the housed. Thus, he receives the derision of some of us who, though never walking in his shoes, boldly declare he wants to be homeless.

If he’s in Santa Barbara, he might land on safe parking. Since 2004, that county has offered a safe parking program to the segment of its homeless population (35%) living in their vehicles. The program, offering 133 spaces in 23 lots overnight, gained national exposure on subscription TV in September. It was built in collaboration with local churches and nonprofits, and remains a point of contact for local nonprofits and social workers. Like organized camps in other cities, the program is an initial solution to homelessness.

In Los Angeles County, some 25% of homeless people live in their cars. So in 2016, that county created a safe parking program modeled on Santa Barbara’s. The cities of San Jose and Saratoga did too. In San Diego, three nonprofits now offer such a program to homeless veterans.

That neither a safe parking nor an organized-camp program has been coordinated in Fresno County—though the city of Fresno is Homeless Hotspot No. 3—is a sad commentary on our morals as a community. Although the local crisis response system is staffed with fine, caring people, we’ve failed to take collective responsibility by using either of these low-cost interventions in our community’s crisis, which outstrips that system.

Make no mistake: A safe parking program isn’t for free parking. Unlike the rules of that board game, it comes with a few strings attached. Participants accept services that are generally understood as helpful to people in their circumstances. Capitalism tempered with compassion, much like the Progressive movement of which Henry George was an early leader. Certainly, these programs aren’t like the variant of the board game where you get $500 just for landing there (big money to a teenager, as I recall).

Your part in the community conversation does matter. If it’s important to learn courtesy around my family’s game table, how much more important to refrain from discourtesy when the stakes are real. If you’re housed, do you entertain notions about a homeless person having it good, being free of worries, wanting to brave the dangers of street life or deserving to face those risks? If so, you rationalize your superior position in the economic game, however unfair.

Acknowledge the person by looking him in the face momentarily, if your day is too busy to give him more time. That is what most of the people desire the most. Almost all communication is nonverbal and imparted quickly. To abstain from false pride, let’s not pretend he has it good. You wouldn’t like to be treated so contemptuously when you’ve rolled the dice and landed somewhere on the losing side of capitalism, would you?

You would long for human kindness to temper your loss, while other people’s snap judgments and hasty assumptions threaten to poison your longing, turning it into bitterness. And that bitterness serves only to divide our community and deepen the homelessness crisis, which is no game we play with tokens but something that involves real money and real lives.

*****

Paul Thomas Jackson is secretary of the Fresno Homeless Advocates (FHA), which has a public group on Facebook and holds in-person meetings in public on the third Sunday of the month. Membership in the FHA is open to anyone demonstrating a serious interest in homeless advocacy.