The great Marxist historian Herbert Aptheker once noted that “history’s potency is mighty. The oppressed need it for identity and inspiration, [and the] oppressor for justification, rationalization and legitimacy; nothing illustrated this more clearly than the history [of] writing on the American Negro people.”

To this point, in July 2023, Florida released its required standards for African American history for its public schools, including this controversial and nonsensical clause: “Slaves developed skills which, in some instances, could be applied for their personal benefit.” This clause represents the exact point of Aptheker’s observation.

The social oppression of Black folk has always revolved around controlling their cognition per their behavior; thus, in every southern slave state, the prohibition against permitting slaves to read and write was an attempt to control the hearts and minds of the slaves.

The oppressors took possession of their labor power and their minds, hoping to justify, rationalize and legitimize a political economy of white over Black. Therefore, whatever skills slaves brought with them from complex urban/agricultural African societies, white slave owners used these skills in their own exploitative interests. Thus, the controversial clause encapsulates much in the historical sense of it all.

However, efforts to whitewash history did not begin with Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis. They began in the history guidelines embedded in the writings of southern historians and others in the first decades of the 20th century, with Harvard’s John W. Burgess stating that “a black skin means membership in a race of men which…has never created any civilization of any kind.”

Another writer and a member of the newly formed American Historical Association, Elliot Paxson Oberholtzer, strongly argued for northern public policy toward the Reconstructed southern states allowing them to return to “home rule.”

Oberholtzer argued that the new Black historian W.E.B. Du Bois’s progressive suggestions on how to reconstruct the South be ignored because radical Republicans “have never seen a n— except for Fred Douglass.”

These racist writings reached their apex in 1930, with authors Samuel Eliot Morison and Henry Steele Commager’s book, The Growth of the American Republic. One passage stated that “Sambo, whose wrongs moved the abolitionists to wrath and tears…suffered less than any other class in the South from its peculiar institution. The majority of the slaves were apparently happy…There was so much to be said as a transition from barbarism to civilization.”

Morison and Commager concluded this section by stating that “the incurably optimistic negro soon became attached to the country and devoted to their white folk.” Multiple millions of American students used this required textbook into the 1960s.

Du Bois, in his monumental 1933 work, Black Reconstruction in America, 1860–1880, critiqued this collection of southern writings in Chapter XVII, “The Propaganda of History.”

Du Bois observed “how the facts of American history in the last half century have been falsified because the nation was ashamed. The South was ashamed because it fought to perpetuate human slavery. The North was ashamed because it had to call in the black men to save the Union, abolish slavery and establish democracy.”

In support of Du Bois, a new generation of Black historians sought to explain in their writings the purpose or meaning of African American history.

Benjamin Quarles argued, in 1964, that Negro history “should be a bridge to intergroup harmony.” The harmony will derive from all Americans reading and learning about the “gifts of Black folk” and their important contributions in making America great in the first place.

First and foremost among these scholars was John Hope Franklin who, beginning in 1947, wrote the audacious work From Slavery to Freedom: A History of African Americans, which is still in print and in its 10th edition.

In fact, most of the Florida Board of Education African American history guidelines follow Franklin’s outline. Thus, you see topics within chapters that cover the horrors and brutality of slavery that led to slave resistance via the Underground Railroad.

Other topics covered are slave rebellions, racism via violent anti-Black race riots and how individuals overcame the harshness of slavery to establish pliable lives either in the urban South or the free North.

Depending on grade level, there are lesson plans that examine African oral traditions; patriots of the American Revolution; Black slave life; free people of color; key figures in the abolition movement; the Emancipation Proclamation; the 13th, 14th and 15th amendments to the Constitution; westward migration and leaders such as Benjamin “Pap” Singleton and frontiersman James Beckworth; and, lastly, the obligatory Buffalo soldiers. Of course, the guidelines required students to learn about famous Black Floridians.

However, it is the clause that appears to celebrate slaves acquiring skills for their benefit that has created the national uproar and led Vice President Kamala Harris to quickly fly to Florida to say that clause is an attempt to “gaslight our history.”

This knee-jerk response is explained in Ralph Wiley’s 1991 book, Why Black People Tend to Shout. Wiley notes that Black folk scream and shout out of pain, frustration, anger and even joy as they confront and overcome white oppression.

For Vice President Harris and many others, that clause revived their anger over “the propaganda of history.”

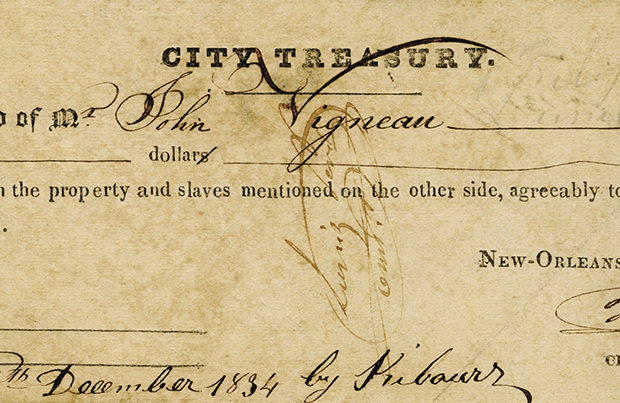

Ironically, slaves were hired out by their owners to other planters for specific skill work learned not in slavery but in Africa, such as carpentry, rice planting and animal husbandry. Slave planters eagerly sought these skilled slaves at the auction block.

A slave agency “negotiated” a percentage of the total paid to their owners for being contracted out. Some skilled slaves were able to accrue enough money to buy not only their freedom but the freedom of their families.

Du Bois and fellow traveler Carter G. Woodson, both with earned doctorates from Harvard University, attacked what Woodson in his 1933 book called The Mis-Education of the Negro. Both firmly thought that the objectivity question in historical propaganda writing about African American history was like “nailing jelly to the wall” but could be defeated by establishing scientific social science journals.

In 1916, Woodson started The Journal of Negro History (now called the Journal of African American History) while Du Bois created, in 1940, Phylon: Journal of Race and Culture.

The term culture in Du Bois’s journal represents today’s realities of the “cultural war” revolving around historical memory and its meaning per African American history.

Lest one forget, DeSantis waded first into these murky cultural waters when he attacked the Advanced Placement in African American history as “woke,” or his version of propaganda. Thus, he eliminated important historical categories such as “Black Lives Matter” from the AP curriculum. To this end, the governor had the Florida legislature pass the Anti-Woke Act (July 2022).

This act represents the ongoing struggle over who shall control the hearts and minds of Black folk and, just as important, white folk.

A similar controversy ensued in 1999 when George H.W. Bush funded the liberal National Center for History in the School to establish national history standards. When Gary Nash’s center completed the curriculum outline, it was attacked by conservatives such as Lynn Cheney who said the guidelines had “too much Harriet Tubman and not enough Robert E. Lee.”

And then, in 2020, conservatives attacked the Pulitzer Prize–winning book The 1619 Project by New York Times African American journalist Nikole Hanna-Jones. The attack focused on her thesis that slavery and racism have been the locomotive of American history.

If the racially oppressive social conditions of African Americans remain, for far too many, the same and if the social relations of racial hierarchy of white over Black is a constant, then the struggle over historical memory and its record will be a dialectic, and, in the words of Harry Edwards, it is the struggle that must be.