By Daniel O’Connell

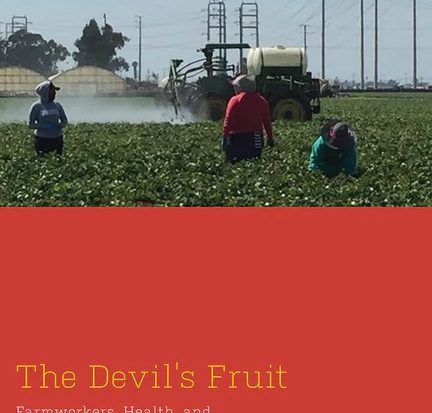

The Devil’s Fruit: Farmworkers, Health and Environmental Justice by Dvera I. Saxton. Rutgers University Press, New Brunswick, NJ, Paperback, $34.95.

Although many of us are familiar with multiple forms of activism, few people are aware of the work of activist scholars.

In The Devil’s Fruit: Farmworkers, Health and Environmental Justice, Dvera Saxton not only assaults the false justifications for industrial agribusiness but also vividly documents the lived, daily experiences of farmworkers’ struggle to survive. Her account is intimate, personal and demanding of action.

Countering dominant narratives (especially racist and anti-immigrant tropes propagated over the last four years by the federal government), the book lifts up farmworkers through their daily lives and their humanity, testifying to their resistance, ingenuity, determination, dignity and cultures of mutual support.

By immersing us within contexts of unrelenting injustice without seeming escape, we follow Saxton on her journey of discovery, accompaniment and solidarity. She brings us into farmworkers’ lives and their experiences of brutal hardship. In her work as an engaged researcher, we also witness her own humanity. Saxton’s work is inseparably an outgrowth of her own empathy and compassion.

Her book is an invitation to all of us to engage, to not turn away, to assist on the most basic levels in the care for our neighbors and fellow community members. To contribute where we can, in our own unique and everyday ways. This invites an encounter with our own culpability.

We exist—often in positions of privilege—in a deeply unjust society. The beginning of our own healing journeys will acknowledge our collective complicity to injustice, particularly when we are not critically conscious in our consumption of food and the food system that produces it. We need to make eating a political act.

As an anthropologist, Saxton entered the Salinas Valley’s industrial agri-scape of despair, pollution and poverty. With the strawberry, the devil’s fruit—la fruta del diablo—used to frame her research, Saxton employs a critical commodity chain analysis to delineate the tentacles and reach of industrial agribusiness as it extends across multinational geographies down into the poisoning of families and layering of toxicity into future generations.

A process of epigenetic disruption is defined as it alters the health of not only farmworkers exposed to pesticides and harmful chemicals but also the intergenerational health consequences for their yet-to-be-born children and grandchildren.

The book condemns an industry that permits the deliberate poisoning of farmworkers. This toxic layering and its invisible harm cumulatively build in ways that are “multidimensional, intergenerational, and multisystemic, from cells and bodies to households and communities, multitiered political structures, and intersecting ecological systems.”

We witness agribusiness expose workers to pesticides, excruciating labor demands, toxic work conditions, inadequate housing, starvation wages, geographic and social isolation, food insecurity and a deadly im/migration system. A lived reality where value is placed upon the production of the commodity above the health, well-being and literal survival of often indigenous im/migrant farmworkers.

Just as Saxton bursts myths, she illuminates truths about our shared humanity with the oppressed. With ethnographic detail of the lives of farmworkers, Saxton befriends, assists and organizes with her compañeros/as. Companerismo—the forming of friendships and working partnerships—becomes a method of her activist research. Her acts of accompaniment open us to farmworkers’ struggles and endurance.

We witness Saxton with her compañeros/as they work to understand unfamiliar systems, try to secure food and healthcare for themselves and their families, and courageously stand together through advocacy and in protest.

At compelling moments, we also witness the hope of immigrants looking for a new life, slamming into a system designed to extract their labor only to abandon them when they are no longer able to work. Through it all, Saxton makes clear that these are the choices and systems that the dominant sociopolitical structure in the United States has erected, sustained and tolerated at great moral jeopardy.

“The widespread and long-standing poverty endured by agricultural workers is not a natural condition. It is rooted in the history of U.S. agribusiness: an economic and ecological system of extraction and monoculture, dependent on the unpaid and underpaid labor and farming and botanical and biological knowledge of Indigenous peoples and Black slaves.”

Activist research is Saxton’s response to injustice, not only as a means of organizing or methodology for building knowledge and power but also as a “way of working and living as a human.” At the center of her approach, we come to understand care as a political act and a way of building community even in the harshest of places—an industrialized food system founded upon discrimination and racialized oppression.

The Devil’s Fruit implores us to assault this economic system where injustice is literally inscribed and embedded into the bodies of farmworkers—a world turned upside down, where the poor and most vulnerable subsidize the luxury of the wealthy and most powerful.

Saxton shows us that research can “instigate change and action” but also, more deeply, introduce us to our humanity and implore us into the community.

*****

Daniel O’Connell is executive director of the Central Valley Partnership, a regional progressive network spanning the San Joaquin Valley. His own forthcoming book is titled In the Struggle: Scholars and the Fight against Industrial Agribusiness in California.