By Hannah Brandt

My grandfather is 93 years old. Most nights, he forgets to take his medication unless I bug him about it: “Did you take your pills yet?” Somehow, he never manages to miss a minute of Family Feud. Yet many other things put him to sleep. For fun, I’ve been keeping track on Twitter: #WhatPutsGrandpaToSleep and #WhatKeepsGrandpaAwake. It is a motley assortment.

On June 13, Hillary Clinton’s speech kept him awake with promises to return the focus of the federal government to America’s working class and poor families. To be fair, Bernie Sanders also held his attention a few nights earlier. When Grandpa was a Dust Bowl kid living in Kansas, he listened to FDR’s fireside chats. He has lived through most of modern U.S. history—from the stock market crash of 1929 to its tumble in 2008.

His family came to the United States from Russia (now Ukraine) in the late 1870s. His dad was born in Manitoba, Canada. His mother came from Russia in the 1890s when she was nine. They were fleeing religious persecution; the imperial government was forcing all boys and men of age into the czar’s army. My great-great grandfather refused on conscience to fight, like centuries of other Mennonite men before him.

Migration was par for the course by then as Mennonites had already left the Netherlands and Germany a couple of generations earlier. We are pacifists, opposed to any violence, going back to the 1500s’ Radical Reformation founding of the church by Menno Simons. Unfortunately, this has meant at times throughout U.S. history we have been unwelcome.

George Washington refused to allow Mennonites to immigrate to the colonies during the American Revolution because they would not take up arms. For this reason, many settled in Canada. Although American immigration policy changed after 1776 to allow Mennonites into the new United States, a sizable community had been established in Canada that continues to this day.

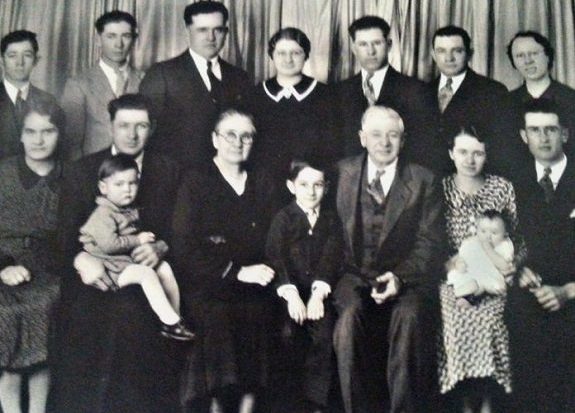

My grandfather’s older siblings were born in Saskatchewan before the family moved in 1920–1921 to Nebraska and then Kansas for better farmland. My grandpa was born a year later. Although World War I ended in 1919, my great-grandfather also worried about his sons being conscripted into future conflicts, as the Canadian government began instituting a draft in early 1918.

Initially, Eastern European immigrants, like my great-great-grandfather, were barred from enlisting because they were not “British subjects.” As the war dragged on and volunteer numbers remained low, this policy was reversed. Although pacifists were granted immunity from conscription, their resistance to “joining up” caused Mennonites to be harassed. They were also open to anti-German sentiment in both countries.

After the deadly dust of the 1930s, my grandpa’s family migrated again from Kansas to California. In his mid-twenties, he met my grandma who worked in a cannery, but as a teen had worked in the fields outside Reedley: plucking up prunes off the ground, laying down papers for raisins, picking cotton.

Her Oklahoma tenant farming family had been hit even harder than his by the Great Depression and was forced to escape the Dust Bowl while she was still a scrawny adolescent. Neither of my grandparents finished high school. My grandma began at Reedley High but was only able to complete a year and a half there because her parents were killed in a car accident when she was 15.

My grandpa was one of two graduates from eighth grade at Harmony School, a one-room schoolhouse in Garden City, Kan., a Mennonite stronghold. When my grandfather was 19 and helping on his father’s farm, the United States entered World War II. Like his father and grandfather, he faced the draft and accusations of being a coward or a traitor. He became a conscientious objector, forced to report to the war office about what he was doing to help the country besides fighting. Fortunately, farming was considered a suitable alternative in that war.

Ever since the 1700s, there has been a vague sense that as pacifists Mennonites are slightly suspicious, slightly not patriotic enough, slightly not true Americans. My father felt it when he was a college student during the Vietnam War. Prepared to move in with extended family in Canada, he steeled himself for the draft card that mercifully never came. Because he led his school’s peace club in protests against the war, a few conservative administrators came to my grandparents’ house demanding if they knew that my dad was a Communist.

My grandparents had obviously lived through the McCarthy era. Far from being political revolutionaries, my grandpa had quietly switched from farmer to carpenter, my grandma worked at a dry cleaners. Although it scared them to have my dad accused of being a Bolshevik, they didn’t denounce his actions against the war. They quietly supported him because they didn’t support America’s actions in Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia either. Many students opposed the Vietnam War, despite serious consequences, like being put on Nixon’s Enemy List.

Few today realize that my grandfather’s generation— what Tom Brokaw famously dubbed “The Greatest Generation” — included pacifists, too. In part, because Brokaw’s immensely popular books focused heavily on World War II soldiers and their families, we tend to envision a whole generation of men wrapped in American flags, tipping back nurses to kiss before shipping out to kill other humans.

However, it may be justified (the Nazis certainly deserve no sympathy) that is the objective of war. Militaries kill, disable and dehumanize until the other side gives in. Those who participate are trotted out each Veterans’ Day, Memorial Day and Fourth of July to be celebrated as heroes. The same men and women often left to die on the streets by a system failing to provide for their war-broken minds and bodies.

It’s as if men like my grandpa never existed, do not continue to exist. Their heroism in quiet resistance erased from commemorations, history books and much of the media. Any mention of pacifism, favorable or damning, is reserved for those who resisted the Vietnam War. Remember that even in World War I, my great-grandfather refused to fight the Kaiser. If the family had already moved to the United States by 1918, when the Espionage Act was passed, he could have been punished with a $10,000 fine and/or imprisonment—possibly for life.

Is pacifism dead? Has the military industrial complex succeeded in eradicating those opposed to war? If you listen to, watch and read most news outlets, you might think so. Few antiwar voices are heard today, less so than 10 years ago. This is partly the fault of a media failing to expose those sentiments, and partly a lack of enough of those voices to demand attention.

In 2001–2003, a Democratic base railed against George W. Bush’s invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq. Yet today, there is nary a peep of resistance to Obama’s military actions, be they drones or boots on the ground. Both have killed thousands of innocent humans in Iraq, Afghanistan, Yemen and Pakistan.

My grandpa is the last of his generation in my family. He has outlived all his siblings, his wife and all but one of his in-laws. He has been the patriarch for decades. Whether our government, our media and our history books continue to try to erase him, he is still here, still a pacifist and still a hero to his family. He is our greatest generation.

*****

Hannah Brandt is a freelance journalist who has previously published in the Community Alliance and the Fresno Bee. Contact her on Twitter @HannahBP2, where she runs @ FresnoAlliance.