Mothers and grandmothers clutched children close on trains rolling through this dry stretch of south Texas, not knowing what waited for them at the end of the line. They were Peruvians of Japanese heritage, kidnapped and brought to the United States in a secret World War II program as trade bait for Americans caught behind Japanese lines.

Recently, survivors of the State Department operation called Quiet Passages returned to the grounds of this erstwhile concentration camp just 35 miles from the Mexican border. They had come to demand justice—reparations or an apology or both—to memorialize history and decry the xenophobia that continues to affect this border region and Asian Americans.

The group, including descendants of those incarcerated, found allies that might have been unexpected 75 years ago: Latino activists and local government authorities, some of whom had helped launch the Latino/Chicano civil rights movement of the 1960s and 1970s.

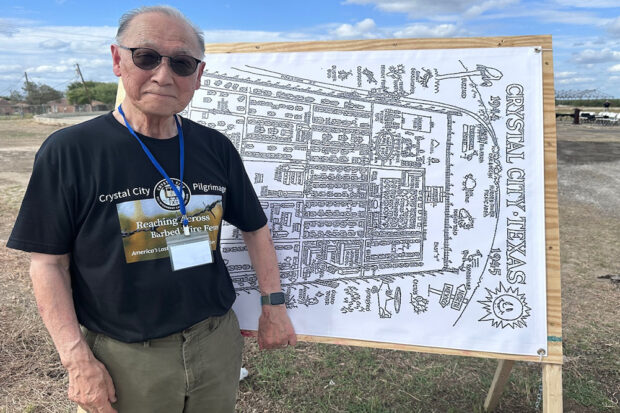

“What’s to prevent this from happening again?” asked Larry Oda, national president of the Japanese American Citizens League, looking over the lonely expanse where up to 4,000 captives lived in barracks—some for more than five years—originally built for migrant Mexican farmworkers. The land was home to scorpions and biting red ants. Armed guards, often on horseback, patrolled.

Oda was born in the camp when his parents, like some other U.S. citizens of Japanese descent, were transferred to join the Peruvians from facilities in Tule Lake, Santa Fe and elsewhere. They were being held under a wartime order that considered them potential enemies.

“Rhetoric like that of the former president leads to this,” Oda said, referring to anti-Moslem and anti-immigrant language used by Donald Trump, leading contender for the Republican candidate for president in 2024. “Rhetoric matters.”

In Crystal City, Latino activists who once struggled successfully in the 1960s and 1970s, as part of La Raza Unida, against local discrimination practices with walkouts and demonstrations, accompanied visitors who came from several states.

“We can fight the white reactionary surge together,” said Manuel Garza, a former local youth activist who is now a field director for the Southwest Voter Registration Education Project.

“It’s about sharing our knowledge, training people to work on issues of voter suppression. People of color are being persecuted right now. We can build coalitions with the Asian community. We can be another country.”

It can’t happen without education about history like that of the Texas concentration camp, said the town’s school board vice president, Cruz Mata, but “it’s not in the books—we need to make it part of the curriculum because history repeats itself.”

Arguably, the U.S. wartime kidnapping operation, which included people of Japanese, German and Italian descent taken forcibly from Guatemala, Costa Rica, Honduras, Bolivia and other countries, might have disappeared from memory except for the work of some on the “Crystal City Pilgrimage” such as Grace Shimizu, whose father and uncle were incarcerated here.

Shimizu directs projects to preserve the captives’ oral histories and to demand redress. Japanese Latin Americans were excluded from the 1988 Civil Liberties Act that recognized the harm done to Japanese Americans.

Or like Bekki Shibayama, who shepherded the case of the captive Shibayama brothers of Lima, including her late father Art, to the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR), which is mandated to protect human rights in the Americas. In 2020, the IACHR affirmed the obligation of the U.S. government to provide “material and moral” redress to the complainants. Neither the Trump nor the Biden administration has complied.

“Here I was going to Crystal City High School in the 1960s, and nobody ever told us we were on the site of a former concentration camp,” said Severita Lara, who once led massive student walkouts until the school board agreed to demands to stop discrimination against Mexican American students—like forbidding them to speak Spanish. Later, Lara became the town mayor.

“Their struggle and our struggle is the same,” said former history teacher Ruben Salazar, who had posted photos of the camp around the school lobby. Salazar also serves on the board of the Crystal City Pilgrimage Committee, which organized the four-day journey.

Japanese began migrating to Peru in the early 20th century on rural labor contracts, picking cotton or harvesting rubber, but eventually owning their own businesses and forming a thriving community more than 30,000 strong. Their children, with Spanish names, spoke Spanish, and were growing up Catholic.

But Peru, where most of the Crystal City inmates came from, refused to take its citizens back after the war. U.S. authorities had seized their passports and birth certificates, so they became “undocumented aliens” when the camp closed. Many went to work at Seabrook Farms in New Jersey for $0.57 an hour in a kind of indentured servitude for years until they could arrange formal release.

“We’re connected in so many ways,” said Kazumu Naganuma of San Francisco, speaking of the Mexican Americans of Crystal City. Naganuma, whose family of nine was brought from Callao, Peru, designed a memorial unveiled at the former camp, recalling two 10-year-old girls who accidentally drowned in the swimming pool that inmates had built for relief from the Texas sun.

“The racism is still here,” he said. “They’re doing it right in front of our faces now.”

As the dry wind blew across the flat acres where the concentration camp once stood, Zavala County Court Judge Cindy Martinez-Rivera said the survivors’ experience “reminds us of a time of erosion of civil liberties, the importance of tolerance and hope for a time when such monuments are not needed.”

Young people said they “came to learn” from their elders, like nurse midwife Keriann Uno, 30, who had flown in from Ketchikan, Alaska. Uno’s great uncle, George Kumemaro Uno, who lived at the camp, was never charged with a crime yet was held by the government until 1947, long after the war ended.

Keriann Uno said that growing up she had “an outsider’s perspective,” only hearing “bits and pieces” of her own history, leading to a feeling of “fragmentation.” Sometimes, families felt shame at admitting incarceration.

“I wanted to hear our stories, and my family’s stories, to understand,” she said. “I think a healing process has started.”