By Vic Bedoian

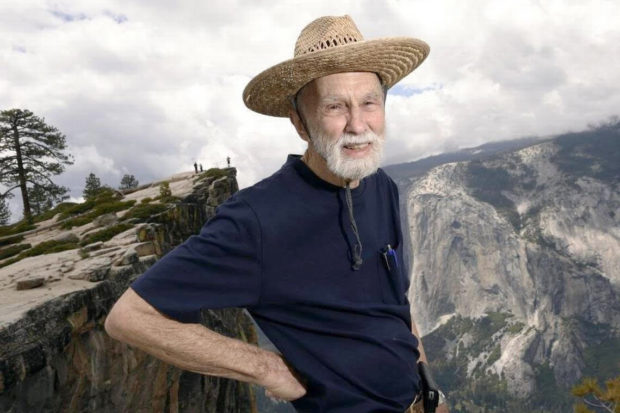

George Whitmore has shaken off his mortal shell and became the stuff of legend for his mountaineering achievements and ceaseless conservation labors. He stood at the pinnacle in both of those endeavors.

Whitmore passed away on Jan. 1 at the age of 90, brought down by complications resulting from Covid-19. The news saddened so many in the local and national environmental movement and his friends in the rock-climbing world.

Articles hailing him have appeared in newspapers and magazines nationwide extolling not just his attainments but, more so, his character and the kind of man he was. Conversations with some of those who toiled with him reveal a life well-lived protecting and enhancing a legacy of wild places in our region for future generations to enjoy.

Although he never bragged about it, hardly even talked about it unless asked, Whitmore was most famous for being part of the team that in 1958 first summited El Capitan. It was at the time a monumental and daring feat. He and his cohorts were at the cutting edge of the sport, along the way inventing equipment and techniques that revolutionized big wall climbing.

Fifty years after that climb, Whitmore referred to El Capitan as a vertical wilderness. “I’ve always been fascinated by things that haven’t been done before or are unknown or are difficult,” he said. “I love wilderness areas that aren’t on maps, where you just have to go and find out on your own.”

His interest in conservation grew out of that climb, ironically, because he objected to how Yosemite officials were treating the climbers.

John Rasmussen, a mountaineer and longtime Sierra Club colleague, worked for Whitmore for decades. “From my understanding, they were quite harassed by the park service on the climb. You know, they were limited to when they could climb. They were harassed about leaving fixed ropes up.”

Whitmore’s conservation deeds were every bit as impressive as his climbing feats and just as impactful. As fellow environmental activists can attest, his knowledge of the Sierra landscape and eye for detail were tremendous assets in doing the actual work of preserving the natural world.

Above all, Whitmore was a mentor, teaching many younger activists the nuts and bolts of analyzing government documents and negotiating with government officials.

Ron Stork is senior policy director for Friends of the River and a longtime conservation leader. He got his start in the Sierra Club’s local Tehipite Chapter, learning the ropes from Whitmore.

“George was rather accessible,” Stork recalls. “I was a young man, but this was in the late ’70s and early ’80s that he had been working on conservation issues for at least a few decades.

“And we were at that time really focused on some big picture planning for wilderness and the beginning of wild and scenic rivers in the Sierra National Forest…It was an opportunity to join in that effort with someone who had been, in large part, one of the founders of these kinds of wonderful designations where we set aside these cherished pieces of lands.

“To work with this guy, it was fun. He was knowledgeable, he was kind, and he was willing to share his knowledge.”

One of the major battles over wilderness development in the 1970s was the plan by Walt Disney Productions for a ski resort smack dab in the wilderness of Mineral King. The massive project would have laid waste to the stunning glacial valley rimmed with the jagged peaks of the Great Western Divide.

Joe Fontaine, a retired high school science teacher in Tehachapi and a former Sierra Club president, has been active in the local and national environmental scene for decades. He worked with Whitmore and many others to stop the project in 1978 after a lengthy battle.

Fontaine also worked with Whitmore as the Sierra Club fought logging in the Sierra’s national forests, seeking to protect those areas as designated wilderness. “He knew the territory really well,” said Fontaine. “He knew those areas in great detail. We both believed those areas should have been in the wilderness system, which much of has since then.”

Fontaine credits their efforts for changes in the outlook and practices of the federal land management agencies, “We put pressure on them as much as we could ourselves. And we talked to Congressmen and people in Washington, D.C., about it too, so I think we did have an influence on the final outcome.”

Mineral King was what inspired Rich Kangas, a retired teacher, as a college student to write a letter to the Fresno Bee opposing the development. Some 15 years later, “There I was at a Tehipite Chapter, Sierra Club conservation meeting in Fresno. I was there, at the home of George Whitmore, one of the leaders in successful opposition to that Mineral King plan, to see what could be done about another Forest Service plan—this one to log Giant Sequoias just north of Grant Grove. I had read about it in the Bee.

“At that meeting, I remember George and Ron Stork discussing wilderness and river issues. When I asked about the giant sequoias, George told me how to get the plan documents and what to do. George told me it was my chosen project. So, I needed to carefully study all the documents, decide what to write in comments and then again later in an appeal.

“I was on my own. He said that as I worked, I should ask for advice and report on progress. George always had good, helpful advice for me and for others during the following monthly meetings. During those meetings, we all heard how the others were progressing on their own projects. That is how George mentored and offered encouragement to so many on environmental projects. That is how we learned.”

Rasmussen similarly worked on many late-night sessions doing the kind of grunt work that most conservation work consists of, “Pretty much it was endless meetings. A lot or most of them were Sierra Club meetings, but there were meetings with the forest service, park service meetings.

“A lot of it was just negotiating, trying to get other people to agree to something, moving things forward, and within the Sierra Club you had bureaucracy worse than the federal government to move things forward. It was good training for the actual federal bureaucracy. You kind of learned from going to Sierra Club meetings how to work with the federal bureaucrats, too. And we had a lot of meetings with them.”

Those were heady days for the conservation movement. Stork recounts, “It was a time in which you could be a real participant in something that would be historic. It would be something that would carry forward into future generations. And we were quite conscious of that as was George.

“So, we were working on expansion of the John Muir wilderness, the expansion of the Minarets wilderness into the Ansel Adams wilderness [and] the creation of the Dinkey Creek wilderness, and the Kings River campaign was part of that. There were wild and scenic river additions to the national park and to parts of the forest.

“And then the area around the Rogers crossing dam was designated as a special management area with kind of quasi wilderness and quasi wild and scenic river characteristics. It was a time in which those things were possible, and those things were possible with community support in Fresno. Those were good times.”

Kangas adds that “in mentoring all of us along his way, George stressed that protecting our public lands takes a lot of time and dedication. When I asked what was important to look for in planning documents, he would always include that ‘the devil is in the details.’”

Rasmussen discloses that Whitmore “was the detail person. He read everything. He could go back and find documents, and his garage had multiple rows of filing cabinets in it.”

Whitmore, kind and collegial as he was, could also be firm with government officials and allies alike. Rasmussen sat through a lot of meetings with Whitmore over the years, “I think he got himself in trouble with a lot of Sierra Club people because he was the one that was practical; he would listen.

“He would determine that, yes, this could be done or couldn’t be done and work to come up with a solution versus standing ground. So, George was in favor of moving things forward versus putting your foot [down] or drawing a line in the sand. And I think that made quite a few people upset.”

Stork reflects that “George had his own internal compass and when he made up his mind, he was not all that dissuadable.” That’s because Whitmore knew what he was talking about.

Yosemite remained Whitmore’s primary focus throughout the years. In 2012, he took part in the latest version of the park’s management plan—always a contentious endeavor attracting intense interest. Decades of experience told Whitmore that resistance to change by Yosemite lovers of all stripes was the biggest challenge for park officials trying to come up with an acceptable blueprint.

But in the end, Whitmore was optimistic. “The process is getting better. They’re learning as they go. Some of the earlier stages in the process were not as hopeful, shall we say. I was beginning to wonder at one point, is this becoming unglued? We’re about to drop into the abyss again? No, things are looking up, this is a good process, and we’re going to end up with a good plan is my guess.”

“We talked about a lot of land-based issues in the conservation meetings, and George knew the ground,” says Stork. “It was quite impressive. We relied on George, and George usually had the answer. It was often quietly delivered in George’s style, of course.

“George somehow in his life had managed to spend the time familiarizing himself with these wonderful landscapes around Fresno that he loved and shared with us, and he emboldened us and empowered us to believe that we could be part of protecting these landscapes. If there’s somebody who taught us how to be an effective environmentalist, that road led to George Whitmore.”

Stork notes that Whitmore was many years ahead of his time in perceiving emerging issues such as plans for the proposed Temperance Flat Dam on the San Joaquin River. “George was aware of almost everything in the Fresno area that one could call environmental from decisions in front of planning commissions and city councils and boards of supervisors and water districts and national forests and national parks. And he kept an enormous file of clippings from newspapers that covered these stories.”

Kangas expresses a common feeling of all who knew him, “George remained constantly dedicated, persistent and tenacious in his conservation work. That dedication and persistence shown by George in his adventure on the nose of El Capitan in 1958 was the same dedication displayed in numerous successful environmental projects he spearheaded in the succeeding six decades. His interest in conservation existed far longer than that.

“I once heard his answer when someone asked how long he had been a conservationist. He answered with numbers that indicated he was born interested in conserving our natural world.”

*****

Vic Bedoian is an independent radio and print journalist working on environmental justice and natural resources issues in the San Joaquin Valley. Contact him at vicbedoian@gmail.com.