By Hannah Brandt

With the surge in Valley Fever cases over the past few years, are we amid a new Dust Bowl? If you live outside California or the Southwest, you may never have heard of Valley Fever, also called “California Fever,” “Desert Rheumatism” or “San Joaquin Valley Fever.” If you’re from California’s Central Valley, you likely have heard of it but may not know more than that the disease comes from breathing in dust. That is all this Fresno author knew before I attended KVIE’s screening of the PBS film Deadly Dust and discussion with UC Davis medical researcher George Thompson.

Valley Fever’s scientific name is Cocci Meningitis or Crytococcal meningoencephalitis. Say that a few times in a row without getting tongue-tied. Since my paraplegic husband had viral encephalitis in college, attacking his brain stem and spinal cord, I know that ending refers to an infection that compromises the central nervous system. The initial symptoms are generally shivers, sore lungs and high temperatures; however, the disease can strike any part of the body. One survivor developed a pressure sore on his ankle.

Some of the survivors of Cocci Meningitis featured in the documentary have permanent physical conditions like paraplegia, impact on the brain, such as memory loss, and vision problems. Common residual effects of the chronic version of the disease are extreme fatigue, joint pain and hair loss.

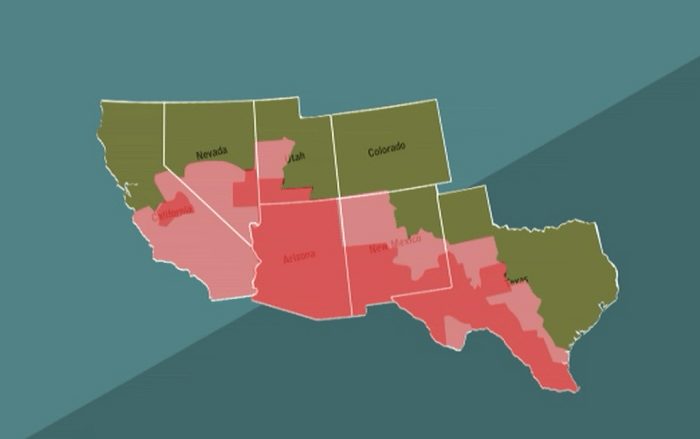

The infection is caused by the fungus Coccidioides immitis, which resides in patches of soil throughout California and the Southwest and is carried through the air whenever a breeze picks up. Anyone who has lived in the Central Valley is familiar with the vast expanses of dusty fields throughout the area.

Anyone who has even driven along the Grapevine on a particularly windy day may feel trapped in a Dorothea Lange photograph and transported back to the Dust Bowl. The barren landscape has a harsh quality, hiding a sometimes brutal disease in the very air you breathe if you roll the car window down or make a pit stop at fast food joints along the road. It takes only that to breathe in the potentially deadly fungus.

Although only 40% of those with Valley Fever develop the chronic condition requiring lifelong treatment, 60% suffer symptoms for six months to a year or possibly show no signs of it at all. Once you have the infection, whether or not you develop its symptoms, you are extremely unlikely to ever be re-infected unless you have a compromised immune system. It is not contagious because once inside the body the fungus becomes a yeast that cannot transmit the disease. Long-term treatment for the chronic version is similar to meningitis, but some forms of treatment are costly. One survivor profiled in the film spends $3,500‒$4,000 a month on his medicine.

Driving through the Central Valley in 2004 was all it took for Jack Miller, a trucker from Idaho, to be infected with Cocci. He now has to travel 1,700 miles a few times a year to UC Davis for treatment. Unfortunately, most doctors are not trained to look for or treat Cocci, especially those practicing outside the areas with the most diagnoses.

Dr. Thompson said he has frequently been called by physicians in other parts of the country with patients who turn out to have Valley Fever—doctors desperate for him to give them a 10-minute crash course on the disease. Many in the medical profession still consider it to be a rare illness. Even those who work in the Valley Fever Belt often barely studied the disease in medical schools in the East.

Due to that misconception, there are no simple, universal tests to screen for Cocci, so many cases are misdiagnosed. Because it can be deadly, tragically, some of the cases are caught too late. One in four pneumonia cases that come into emergency rooms in the Central Valley are in fact Valley Fever. Many of those individuals are sent home not knowing they have the condition.

In some cases it is only much later, after being screened for diseases like cancer, that scans will reveal scarring on the lungs suggesting the patient probably had Valley Fever earlier in life. While patients have the infection, their CT scans will only reveal a lung infection, not Cocci specifically. Antibody tests vary from 60% to 90% accuracy detecting the disease.

In addition to a lack of effective, routine screenings, there is no vaccine for Valley Fever. Because the disease is centered in a relatively small area of the country, funding has been scarce until recently. Dr. Thompson and others who study the disease are optimistic about the future of treatment as the National Institutes of Health and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention have joined in a study of 1,000 prospective patients diagnosed with pneumonia who are at high risk for Valley Fever. This could lead to more effective screenings, treatment, and even a vaccine. Those who are at highest risk for contracting Cocci are pregnant women (as the fungus thrives in estrogen), people who work in archaeology and agriculture or those with hobbies such as flying model airplanes, which take them to open fields.

Those of Filipino and African-American descent also have higher probability than other ethnic groups of contracting Valley Fever. The best explanation researchers have for this is that the genetic features that put these people at increased risk for Valley Fever are favorable for combating other infections more common to their ancestral homes. A group often overlooked when the public considers risk factors is the prison inmate population residing in the large incarceration complexes in the Central Valley. Prisoners account for some of the 150,000 cases of Valley Fever each year.

Those who live and work in high-risk parts of the country have developed some techniques to fight the disease. Many spray their fields to keep the dust from kicking up with the wind that consistently sweeps through those wide open spaces. This is not necessarily the best tactic, according to Dr. Thompson, because the fungus grows in the wet soil. The spores are more likely to metastasize and then be spread as soon as the field dries.

Outside the archaeological and agricultural industries, one solution is to pave over the fields. Many prisons have used this method, becoming the cement-encased cities we see in the distance while driving along Central California freeways.

Dr. Thompson cautioned that if our current drought involves severe windstorms as happened in the drought of 1977, we could see more cases of Valley Fever further afield. During that drought, there were a large number of cases in Sacramento and some even as far away as Washington State. The wind is a powerful force that can carry dust for many miles if Mother Nature so desires. In the open land of the Valley Fever Belt between Bakersfield and Fresno, the dirty powder hangs like a cloud over the people who live, work, and play there. This ethereal substance can seem nothing more than an annoyance, stinging the eyes and sticking to sweaty arms, but it exacts a heavy toll on those who breathe in at the wrong time.

*****

Hannah Brandt is a freelance journalist in Fresno. Contact her via Twitter @HannahBP2. Jason Shoultz’s documentary film, Deadly Dust, may be viewed at http://vids.kvie.org/video/2365207702/.