By Tom Frantz

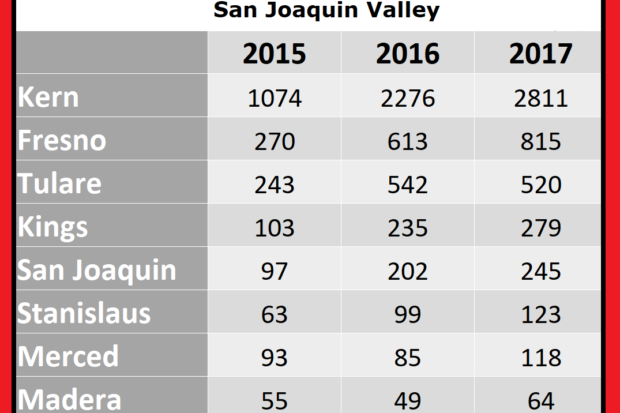

The last three years have seen rapidly increasing cases of Valley Fever in the San Joaquin Valley (SJV). Recent growth in the Valley is 150%, whereas Southern California saw a 75% increase. Part of the growth could be due to better detection and awareness, but rates of the disease are, by far, the highest in the SJV, where more than 125 cases per 100,000 residents were diagnosed in 2017.

In the rest of the state, the rate is less than 10 per 100,000. The only other area in California with higher-than-average rates is the central coast.

Valley Fever is a fungal disease, and the infectious spores are spread through the air and taken into the body through the lungs. These spores originate in the soil and are spread when the soil is disturbed and spread as dust in the air. The infected person often experiences flu-like symptoms. Everyone seems to have an equal chance of getting the disease, but African Americans and Hispanics are hospitalized more frequently with more severe symptoms.

People who work outside and live in less insulated homes are more exposed to Valley Fever. There may even be a migration of valley dust to the central coast during stagnant air periods. The San Joaquin Valley is certainly a dusty place, especially in the fall when high pressure dominates the region. Certainly, controlling dust levels in our air could reduce Valley Fever rates. The San Joaquin Valley Air Pollution Control District, a purported health agency, should therefore be very concerned about these recent increases.

The air district claims that the Valley met the federal health standard for PM10 (coarse particulate matter or dust) many years ago. The last dust rule changes were in 2006. The air district does not feel any need to strengthen dust control measures. But, this policy should probably change.

Looking at PM10 levels in the San Joaquin Valley over many years, it is clear there is more dust today. From 2003 to 2005, the three-year annual average was around 46 micrograms per cubic meter. The standard is 50. Looking at 2015 to 2017, the 3-year average climbed to 55 micrograms. There is also a 24-hour standard of 150 micrograms. That level was exceeded 10 times in 2017. In other words, our dust levels have been getting worse and we no longer meet the standard.

The air district claims to have a maintenance plan in place that prevents dust levels from getting worse. So, what the hell is going on? The air district cries that drought and exceptional events are the causes of this increased dust. It claims that without those events levels of dust would be lower than ever because of their rules. But recent high levels since the drought ended have shown that excuse to be false.

The months when dust has increased the most are August and September, which are right in the middle of the almond harvest season. It is not surprising to see higher dust levels during this time of year because almond harvest is a dusty process. On top of that, the acres being harvested statewide have increased from 850,000 to one million over the past three seasons and are still climbing.

Is there a relationship between Valley Fever and dust from almond harvest activities? Could it be that the undisturbed, moist soils in orchards are conducive to Valley Fever spore growth? No one is talking about it.

In the meantime, our dust levels are out of compliance with federal health standards. It is time for the air district to look at more stringent ways to reduce all dust wherever it occurs. They should not be throwing up their hands and blaming the weather. Fortunately, there is a lot that can be done.

First, almond harvest dust may or may not cause Valley Fever, but it is definitely a nuisance and it is absolutely pushing us over the health standard. Fortunately, it can be controlled. There is incentive money available and aimed at helping farmers purchase low dust almond harvesters. The incentive money should be increased in the short term, along with a backstop rule requiring all harvesters to have the best available dust control technology by 2023.

Second, more road shoulders should be paved or treated to control dust. It is worth the money and there must be strong mandates for each county along with state help.

Third, construction and industrial sites, with earth moving or loading and unloading of dusty materials, can be better regulated and current rules better enforced.

Fourth, agricultural processing sites, like almond hullers, cotton gins and feed mills, where trucks and trailers are moving around either daily or seasonally, need to be told to eliminate all visible dust.

Fifth, oil field vehicles should not be allowed to leave a trail of dust on their private roads.

Finally, using leaf blowers to blow dust off sidewalks and driveways must be prohibited at homes, businesses and schools. We can do better.

*****

Longtime clean air advocate Tom Frantz is a retired math teacher and Kern County almond farmer. A founding member of the Central Valley Air Quality Coalition (CVAQ), he serves on its steering committee and as president of the Association of Irritated Residents. The CVAQ is a partnership of more than 70 community, medical, public health and environmental justice organizations representing thousands of residents in the San Joaquin Valley unified in their commitment to improving the health of Californians. For more information, visit www.calcleanair.org.