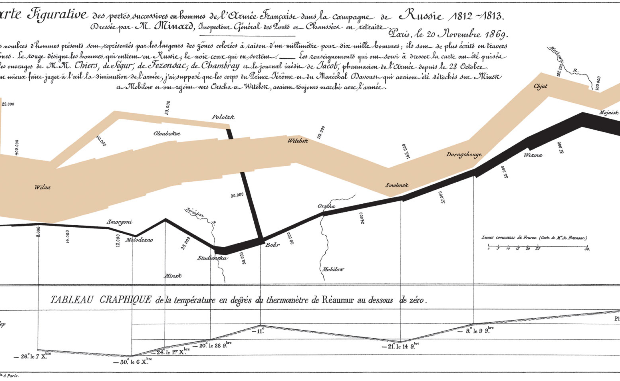

It is winter and I am drawn to a large map, designed in 1869 by French civil engineer and statistician Charles Minard. It is a graphic of the 1812 march of Napoleon and his imperial Grande Armee, chronicling his disastrous attack on Russia.

My fingers trace the route taken by Napoleon’s force of more than 600,000 men from where they crossed the border and rushed almost 1,000 kilometers to lay siege on Moscow. It was a campaign of skirmishes, guerilla warfare and attrition from fighting and starvation.

The Russians exercised scorched-earth tactical withdrawals ahead of the advancing French, leaving no sustenance behind for consumption by the invaders. It was in this state that Napoleon found and seized Moscow in September 1812. Expecting to enter triumphantly and receive the keys to the city, he found instead, an empty shell, bereft of people, supplies and shelter; major portions being consumed by fires. His Grand Armee, reduced to barely 100,000 starving and exhausted troops, had achieved an empty victory.

On October 15, 1812, they began a forced withdrawal, which deteriorated into a disorganized dash across an increasingly hostile landscape, now besieged by the unforgiving Russian winter. The accompanying chart’s line of retreat shows the continued shrinkage of the French forces as the men succumbed to wounds, illness and starvation or froze to death, with temperatures dipping below minus 30 degrees Centigrade (minus 22 degrees Fahrenheit).

Minard estimated that by December 1812 only 10,000 French soldiers survived, whereas other statisticians place that number at almost 70,000. Whichever is correct, the sad truth is that more than half a million soldiers of the Grand Armee would never again see their homes. Charles Minard’s depiction, known by some as “the best statistical graphic ever drawn” is also widely appreciated as one of the most outstanding historical statements against war and its costs in human lives.

Stalingrad, 1942–1943

The pages of history turn to the autumn of 1941, prior to the entry of the United States into World War II. Another seemingly invincible army plunges into the foreboding Russian landscape. This time, it is Hitler’s divisions that are confident of a short engagement, apprising Moscow and Stalingrad as minor stepping stones toward the total domination of Russia, so that they could then turn to the annihilation of Great Britain and the weakened allies.

Photos show young men, smiling and handsome in their summer uniforms, many with blonde hair and tanned faces. They march triumphantly, weapons slung over their shoulders, across a dry, sun-bathed plain.

Estimates vary, but generally describe the attacking force as comprising about 364,000 men. They were the elite forces of Germany: a lightning fast juggernaut of infantry, Tiger tanks, artillery and the total air dominance of the Luftwaffe. Comparisons can be drawn with the current image of today’s U.S. military: singularly capable of fighting and defeating two or more opposing forces in distinct theaters or areas of operation.

Two essential elements clearly placed them above most of their opposition: they had a superior sense of military strategy and discipline and a fanatical dedication to their “fatherland.” Hitler’s tirades had mesmerized the nation’s population into the profound belief that everything they did—each sacrifice, tribulation, death and even genocide—would provide for a free and secure Germany.

They killed and died so their families could be safe and prosper, as Hitler’s words proclaimed, “The heroic struggle of our soldiers on the Volga should be an exhortation to everyone to do his maximum in the struggle for Germany’s freedom and our nation’s future, and in a wider sense for the preservation of the whole of Europe.” Today, these words continue to resonate with a fearful nation, adrift in a seemingly hostile world, pushing the population to extremes of preemptive violence.

The Kessel

As winter approached in 1942, Hitler’s fanaticism and belief in the invincible German Army caused him to split with his field commanders and commit a glaring violation of basic military doctrine. He committed his forces to the achievement of two separate objectives against major opposing forces.

Hitler struck at the oil fields of the Caucasus while simultaneously attacking the industrial stronghold of Stalingrad—both daunting tasks. He underestimated the socialist mode of production, which had raised the industrial capacity of Russia, especially in the fabrication of cheap, crude, but effective, weapons of war, like the thousands of T-34 tanks that vastly outnumbered the German Tigers.

More than that, Hitler underestimated the resilience and spirit of the Russian people. The whole population threw themselves into the war effort. They dismantled whole factories and moved them to isolated areas where they continued to operate untouched. The factory workers became the militias that tenaciously defended their plants to the end.

The soldiers of the 16th Panzer Division were confronted with dozens of anti-aircraft batteries that were wheeled about and leveled at their armor, inflicting heavy losses. They were shocked when they discovered that they were “manned” by Russian women who matched them shot for shot until their placements were destroyed.

Finally, Hitler did not allow the German public to know the truth of the dehumanizing conditions that their sons, brothers and fathers faced in the killing fields and ruins of Stalingrad. In addition to the overwhelming waves of tanks, airbursts and Russian charges, the proud and disciplined German Army fought dysentery, starvation, lice and the freezing cold without the benefit of proper winter gear.

Dressed in rags and in this dehumanized state, the Germans continued to effectively deal death to their numerically superior enemy, generally causing twice as many casualties as they suffered. Nonetheless, by November 1942, they were caught in a double encirclement that became known as the Kessel, or Cauldron. Hitler refused to allow the 6th Army to break out and withdraw in defeat.

On February 2, 1943, after 76 days and nights, 60,000 dead and 130,000 captured, the battle for Stalingrad was over. There is confusion over the numbers, due to the large presence of Romanians, Italians and even Russians who fought on the German side. Reminiscent of Napoleon’s legions, of the Axis forces that participated in the invasion of Russia, more than a half million men died, far from their homes.

As I read and reread the stories of individual soldiers and whole companies that marched into oblivion, I succumb to a profound sadness. I reflect on page after page of the atrocities that were committed, first against the Jewish populations, then against the Slavs in the invasion of Russia.

Forty thousand civilians were killed during the first week of bombardment in Stalingrad. Thousands more died under the guns or from disease, starvation and the cold. By the end of the war, civilian casualties, though difficult to ascertain, are thought to have been 12 million–18 million, with total war dead of the Soviet Union reaching perhaps 24 million, more than four times the total German war dead.

The Red Army suffered almost half a million dead in Stalingrad alone: more than the United States total dead of around 420,000 for the whole war. Only about 5,000 of the 360,000-strong German 6th Army would return to their homes after many years of captivity.

Historic Parallels and Lessons Learned

By the time the United States was fully engaged in the war, Germany’s fate had been decided in the Kessel. It was acknowledged by Hitler himself when he told his generals that their failure to take the Caucasus would mean having to end the war.

As with any great tragedy, we try to draw something positive from the deadliest military conflict in history, or, at least enough to maintain hope for the future of mankind. And stories of humanity are there to be found.

- A wounded German officer found compassion in two Russian women who rubbed his legs to prevent frostbite commenting with sadness of his youth and apparent proximity to death.

- Another group of soldiers stumbled on several Russian women in a bombed out house, who traded fresh bread for a hunk of frozen horsemeat.

- Russian peasants came to the aid of German prisoners with water and helped them with their burdens during forced marches.

- It is believed that some German soldiers may have escaped the Kessel and found their way to remote villages where ancient customs would see that they were cared for.

We can draw hope from the courage of the German officer corps that launched a series of unsuccessful plots to assassinate Hitler and head off the looming disaster. Hundreds of the plotters were summarily executed or marched off to trial and firing squads. German officers and soldiers helped hundreds of Jews escape the Nazi death camps.

It is the winter of 2011, and our nation faces economic disintegration, internal strife and divisions, with cults based on fear, narrow nationalism and an obsessive preoccupation with our decline. They are attempting to transform these negative trends into a collaboration between the old guard conservatives and the naïve and uninformed. It has already manifested itself in disastrous military debacles that have sucked the lifeblood from our economy. It threatens to replace our democratic principles and respect for other nations with internal cleansing and external expansion based on violence without restraint. We have gone full circle to again face “The Anatomy of Fascism.” It was this lesson that the Soldiers of the Russian Winter paid for with their lives.

Footnote: Two portrayals of this historic showdown tell the same story from different points of view. Stalingrad, written by German Army correspondent Heinz Schroter and published in English in 1958, sees this human tragedy from the perspective of the highly touted 6th Army, which Hitler once boasted, “could storm the heavens.” The other book is Antony Beevor’s study entitled Stalingrad: The Fateful Siege: 1942–1943. This narrative includes extensive research from archives in Germany and the Soviet Union, interviews and unpublished accounts. For a reference on the definition of fascism, see Robert O. Paxton, The Anatomy of Fascism (2004).