By George B. Kauffman

According to the late Ulf Lagerkvist, a member of the Swedish Academy of Sciences who participated in judging nominations for the Chemistry Prize, “It is in the nature of the Nobel Prize that there will always be a number of candidates who obviously deserve to be rewarded but never get the accolade.”

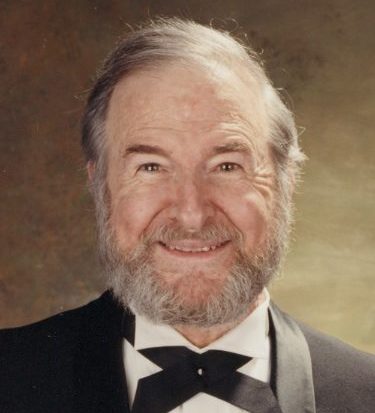

Usually, a losing candidate merely accepts the injustice. But in the case of the 2003 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine of $1.3 million, awarded 10 years ago to University of Illinois chemist Paul C. Lauterbur (1929‒2007) and University of Nottingham UK physicist Sir Peter Mansfield (b. 1933) “for their discoveries concerning magnetic resonance imaging,” the undoubtedly deserving candidate, Raymond Vahan Damadian, M.D. (b. 1936), an American of Armenian descent, did not take this injustice lying down.

A group called the Friends of Raymond Damadian protested the denial with full-page advertisements, “The Shameful Wrong That Must Be Righted,” in the New York Times, the Washington Post, the Los Angeles Times and Stockholm’s Dagens Nyheter. His exclusion scandalized the scientific community in general and the Armenian community in particular. He correctly claimed that he had invented magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and that Lauterbur and Mansfield had merely refined the technology. On Sept. 2, 1971, Lauterbur acknowledged that he had been inspired by Damadian’s earlier work.

Because Damadian was not included in the award even though the Nobel statutes permit the award to be made to as many as three living individuals, his omission was clearly deliberate. The possible purported reasons for his rejection have included the fact that he was a physician not an academic scientist, his intensive lobbying for the prize, his supposedly abrasive personality and his active support of creationism. None of these constitute valid grounds for the denial.

The careful wording of the prize citation reflects that fact that the laureates did not come up with the idea of applying nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR; the term was later changed to avoid the public’s fear of the word nuclear even though nuclear energy is not involved in the procedure) to medical imaging. Today, MRI is universally used to image every part of the body and is particularly useful in diagnosing cancer, strokes, brain tumors, multiple sclerosis, torn ligaments and tendonitis, to name just a few conditions. An MRI scan is the best way to see inside the human body without cutting it open.

The original idea of applying NMR to medical imaging (MRI) was first proposed by Damadian, a physician, scientist and assistant professor of medicine and biophysics at the Downstate Medical Center State University of New York in Brooklyn. Growing up in Forest Hills, N.Y., he attended the Julliard School and became a proficient violinist. When he was still a boy, he lost his grandmother to a slow death by cancer. He vowed to find a way to detect this dreaded disease in its early, still treatable stages.

Using a primitive NMR machine, Damadian found that there was a lag in the relaxation times between the electrons of normal and malignant tissues, allowing him to distinguish between normal and cancerous tissue in rats implanted with tumors. In 1971, he published the seminal article for NMR use in organ imaging (“Tumor Detection by Nuclear Magnetic Resonance,” Science, March 19, 1971, Vol. 171, pp. 1151‒1153). Nevertheless, many individuals in the scientific and NMR community considered his ideas farfetched, and he had few supporters at the time.

However, Damadian received a grant from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) in 1971 to continue his work. He proposed to use whole body scanning by NMR for medical diagnosis in a patent application, “Apparatus and Method for Detecting Cancer in Tissue,” filed March 17, 1972 (U.S. Patent No. 3789832, issued Feb. 5, 1974). By February 1976, he was able to scan the interior of a live mouse using his FONAR method (field focused nuclear magnetic resonance).

In 1977, using his machine christened “Indomitable,” now preserved in the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C., Damadian tried to scan himself, but the test failed because of his excessive weight. On July 3, 1977, he obtained the first human NMR image—a cross-section of his slender postgraduate assistant Larry Minkoff’s chest, which revealed heart, lungs, vertebræ and musculature. Minkoff had to be moved over 60 positions with 20 to 30 signals taken from each position. Congratulatory telegrams poured in from all over the world, including one from Mansfield.

In early 1978, Damadian established the FONAR Corporation in Melville, N.Y., to produce MRI scanners. Later that year, he completed his design of the first practical permanent magnet for an MRI scanner, christened “Jonah.” By 1980, his QED 80, the first commercial MRI scanner, was completed.

The MRI imaging industry now expanded rapidly with more than a dozen different manufacturers. On Oct. 6, 1997, the Rehnquist U.S. Supreme Court awarded Damadian $128,705,766 from General Electric Company for infringement of his patent.

Damadian is universally recognized as the originator of MRI (by President Ronald Reagan, among others) and has received numerous prestigious awards such as the National Medal of Technology in 1988, the same year in which he was inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame. He was named the Knights of Vartan’s 2003 “Man of the Year,” and on March 18, 2004, the Franklin Institute of Philadelphia bestowed its Bower Award on him for his development of MRI.

*****

George B. Kauffman, Ph.D., chemistry professor emeritus at California State University, Fresno, and Guggenheim Fellow, is a recipient of the American Chemical Society’s George C. Pimentel Award in Chemical Education, the Helen M. Free Award for Public Outreach and the Award for Research at an Undergraduate Institution, and numerous domestic and international honors. In 2002 and 2011, he was appointed a Fellow of the American Association for the Advancement of Science and the American Chemical Society, respectively.