Beginning at Merritt College in Oakland in 1961, Bobby Seale and Huey P. Newton organized the Negro History Fact Group, which was the first Black history course offered in higher education. The course covered biographies of W.E.B. Du Bois, Carter G. Woodson, Nat Turner, Marcus Garvey and world leaders such as Kwame Nkrumah, Julius Nyerere, Mao Tse-Tung, Che Guevara and others. Obviously, Seale and Newton’s interests in socialist world leaders became a part of their platform when they organized the Black Panther Party as a Marxist-Leninist cadre.

At that time, the classic works on Black history were not known, and many of these works were out of print. These classic works are James W.C. Pennington’s A Textbook of the Origins and History of the Colored People (1841); William Wells Brown’s The Black Man: His Antecedents, His Genius and His Achievements (1863); and George Washington Williams’ History of the Negro Race in America, 1619–1880: Negro as Slaves, as Soldiers and as Citizens (1883).

However, with Woodson, starting in 1926, the Negro History Week celebration of sheroes and heroes in churches, fraternities, sororities and a wide variety of Black social clubs only enhanced the recognition of Black achieving giants of the past. Many of these groups used Woodson’s Negro History Bulletin (1937) as a popular resource.

The grounding of the Black past at the “folk” level eventually made its way into higher education with the hiring of Nathan Hare, in February 1968, at San Francisco State and the establishment of the first Black studies program. The basic text in this program and others to follow was either John Hope Franklin’s From Slavery to Freedom or Ebony magazine journalist Lerone Bennett’s survey, Before the Mayflower: A History of Black America (1964).

In the next year, 1969, both UCLA and Cornell University began their programs. Of course, at Cornell, it took the armed takeover by Black male students of the Willard Straight Hall and the threat that “Cornell has 24 hours to live” for it to establish its Africana Studies Research Center under James Turner.

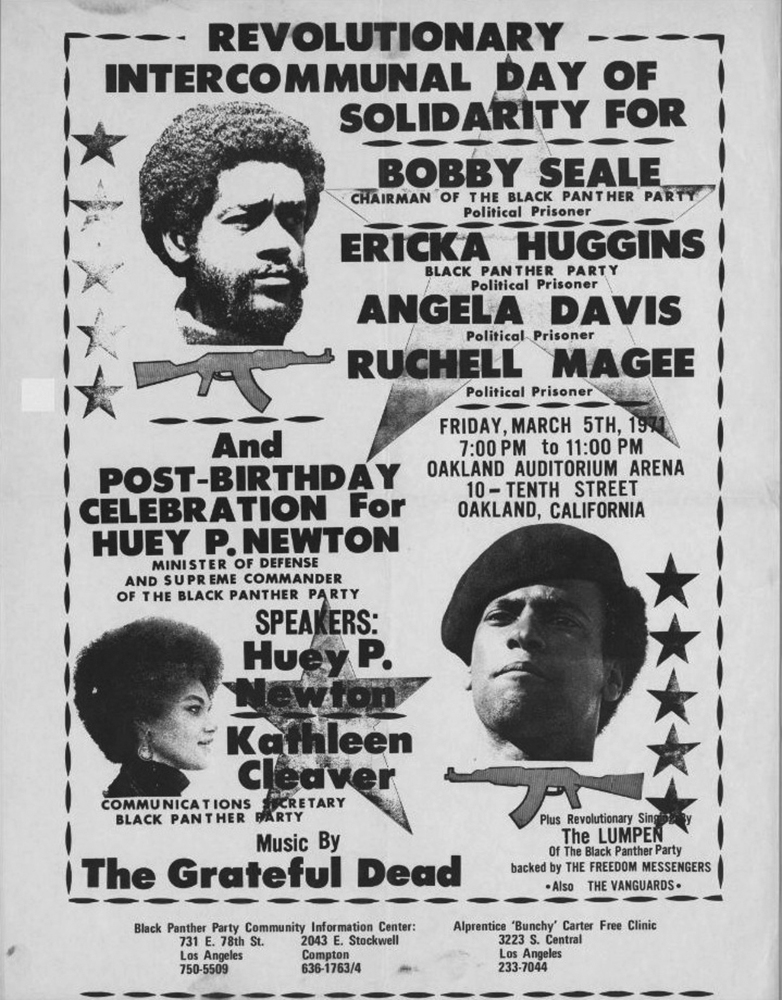

At UCLA, the movement and its leaders created the Center for African American Studies (CAAS). However, that leadership was contested as one entity, Organization US, battled against the Black Panther Party (BPP) regarding who would control the naming of the first chair of the Center. This contestation came to a violent point on Jan. 17, 1969, when US members shot and killed two BPP members, Alprentice “Bunchy” Carter and John Huggins Jr.

Given the armed Cornell University incident with that of the CAAS, historians Quintard Taylor and Herbert Ruffin assert that Black studies is the “only academic discipline born of the political struggles around Black Power.” This was not the case in Atlanta where Vincent Harding created the short-lived The Institute of the Black World.

In rapid succession, hundreds of similar programs were created across the nation like “a spark starting a prairie fire.” And, in 1975, Dr. Bertha Maxwell-Roddey organized the National Council of Black Studies (NCBS) at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte. Interestingly, one noted active member of the NCBS was Donda West, the mother of rapper Kanye West.

Dr. West, while teaching at Chicago State University, founded the Gwendolyn Brooks Center for Black Literature and Creative Writing. At present, Dr. Valerie Grim of Indiana University–Bloomington is the president of the NCBS.

By the 1980s, one could locate Black studies programs at the University of Montana, the University of Nebraska–Omaha, the University of Houston, the University of Arizona and in the nations of Brazil, Canada, Colombia and Great Britain. By 2008, these undergraduate programs in Black studies were strong enough to create more than a dozen doctoral programs at higher education institutions such as the University of Minnesota, Harvard University, Temple University, Northwestern University, Michigan State University, UC Berkeley, Brown University, Indiana University and the University of Pennsylvania.

Corresponding to these new academic units was the publication of new scholarly journals such as the Africana Review, Africology, Afro-Americans in New York Life and History, Callaloo, Griot, Black World, Western Journal of Black Studies and Black Scholar.

Today in 2023, one would be challenged to precisely count the thousands of African American survey history courses offered in secondary schools across the nation. In one case, in Fresno, Bullard High School offers a Black history course started by a father, J. Clark Sr., in the 1970s that is still being taught by his son, J. Clark Jr. The Clarks are white Americans. However, the son is teaching the social studies course within an Afrocentric paradigm using the works of Cheikh Anta Diop.

If one attended multiple scholastic social studies teacher conferences, one would hear that many teachers of African American survey history are using, as a pedagogical resource, the world-renowned website, Blackpast.org.

This perspective is an attempt to trace, via Black history movements, the intellectual antecedents of the recent Florida controversy with its governor, Ron DeSantis, who is seeking to regulate what he called “woke” history by restricting history instruction to what history will not threaten the comfort level “of white folk.”

This level was first revealed by Langston Hughes in his 1934 book The Ways of White Folk, which is a literary narrative in which Hughes explores the social relations of Blacks versus whites in time and space. In his multiple short stories, Hughes delves deep into the intimacies of whites over Blacks in the historical context.

It is clear to the critical thinker that Gov. DeSantis wants such a fictional approach to continue in the hard knocks over who shall control Black folks’ history. African American history is now solidified in high schools, colleges and universities nationwide, and not one or several governors with their own anti-woke legislation can stop the needs of Blacks to control their history, which inspires and directs “the struggle that must be.”

One governor, Glenn Youngkin of Virginia, in 2022 won his election by stoking fears that one Black history pedagogical theory, also known as critical race theory, harms the hearts and minds of young white children.

If the racially oppressive social conditions of African Americans remain, for far too many, the same, and if the social relations of racial hierarchy of white over Black is a constant, then the struggle over historical memory and its record will be a dialectic, and in the words of Harry Edwards, it is “the struggle that must be” or “A Luta Continua.”