By Boston Woodard

“Every human being has a spark of something in them that can be ignited for the good of mankind…Someone getting out of prison has to make their own choices. Whether they end up sleeping under a bridge or whatever, they have to make the choice not to commit another crime. But when someone lends a helping hand, it makes a world of difference.”

These are the words of former prisoner Guillermo Willie being interviewed about the Poetic Justice Project (PJP) by an online news magazine (www.anewscafe.com). An actor in several PJP productions, Willie is now on the advisory board for this innovative reentry program that provides formerly incarcerated people with opportunities to involve themselves with the arts.

The PJP, based in Santa Maria, was founded by Deborah Tobola in 2009. A former journalist and teacher with a master of fine arts degree, Tobola taught writing classes for 12 years at prisons in Tehachapi, Wasco, Delano and the California Men’s Colony West Facility. Later, she facilitated music, art and drama classes for the Arts in Corrections program, which has since been discontinued due to budget cuts.

Tobola has a passion for working with imprisoned people involved with the arts. “The qualities it takes to be a successful artist—commitment, discipline, honesty, integrity—are the same ones that could help these guys in everything,” said Tobola.

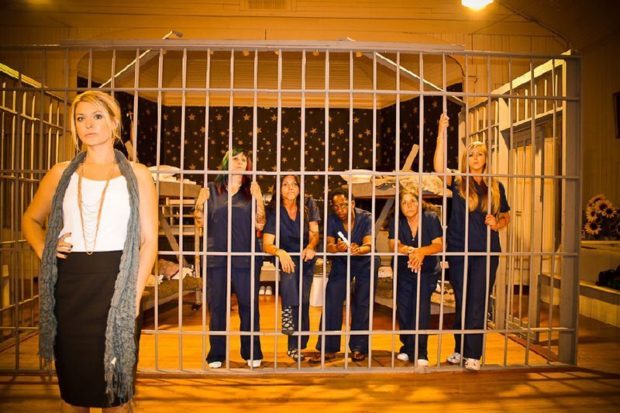

“PJP’s motto, ‘Unlocking hearts and minds with bold, original theater’ works both ways,” said Tobola. “For the actors, it’s powerful for them to be accepted by the audience. They have felt stigmatized. For the audience, the performers may make people feel differently about men and women who have been incarcerated and are seeking to return [to society] as part of the community.”

Tobola’s late father was at one time a prison guard. Although her dad passed away before she began working behind prison walls, she remembers he was a great mentor. “He would have loved what I am doing today,” she said.

John Steinbeck was one of her father’s favorite writers, and Tobola said he would have particularly loved PJP’s production, Of Men and Mice, based on Steinbeck’s novel.

PJP adviser Willie, who played George in Of Mice and Men, also performed in several other PJP productions. “Everyone reentering society from behind prison walls should have a vehicle for expression,” he said. “Many parolees get ridiculed, put down and shunned because of their criminal history. It’s sort of a sad mode of expression that folks adapt regarding ex-cons, and it shouldn’t have to be that way.”

There are approximately 75 ex-prisoners, both men and women, participating in the PJP. Women make up approximately a third of the participants.

The PJP has presented seven plays, many of them original. In addition to Of Men and Mice, they include Off the Hook by Tobola, The Exonerated by Jessica Blank and Erik Jensen, Blue Train by Cliff Ray, What If? by students at Los Prietos Boys Camp, Planet of Love by Tobola and Women Behind Walls by Claire Braz-Valentine.

This fall, PJP plans to do In the Kitchen with a Knife, a murder mystery, and four PJP actors will appear in the play, The Hairy Ape, in Arroyo Grande.

When asked if she missed working behind prison walls with artists, Tobola said, “I do miss it very much.” She recently had a chance to do a 12-week workshop on the arts at the Los Prietos Boys Camp. During this time, the students explored creative writing, art, music and theater improvisation; their efforts culminated in the PJP play, What If?

For artistically talented people reentering society after imprisonment, the PJP can be a lifesaver. Recidivism has skyrocketed, overall rehabilitation programs have diminished and promising opportunities are few and far between for those adjusting to outside life.

At least 70% of those released from California prisons return, at a cost of nearly $56,000 annually per prisoner, according to aNewsCafe.com.

At least 70% of those released from California prisons return, at a cost of nearly $56,000 annually per prisoner, according to aNewsCafe.com.

The PJP attempts to punch a hole in these grim statistics. “If we keep 20 people out here from going back to prison,” said Tobola, “we save taxpayers $1 million annually.”

Former prisoner Willie added, “Statistics dictate that many parolees will soon go back to crime. Lending a helping hand to men and women who truly want to turn their lives around is a noble gesture. That is exactly what the PJP does for people like me.”

The PJP operates on funds donated to the program. Various venues are used to practice and prepare for the plays. Sometimes, local churches step up and provide space and time for the PJP to get its production ready. In return, some of the volunteers and actors do work for the church—construction, painting, cleaning or whatever is needed.

The PJP (www.poeticjusticeproject.org) is interested in looking at original plays. Stories can be about prison, redemption, points of view from prisoner’s families, associates of prisoners or the prison system, etc. Stories should be serious and/or lighthearted. The PJP is not looking to be a forum for personal or political complaints or to demean anyone or the prison system.

Tobola emphasized that the PJP wants to give parolees the opportunity to feel connected after returning to society. “The project also gives people a way to contribute to the community and at the same time have a creative community of their own, with actors and technical people, so it’s like a big family,” said Tobola. “We hope to enlighten people to this invisible subculture.”

*****

Boston Woodard is a prisoner/journalist who writes for the Community Alliance and the San Quentin News. He wrote for the Soledad Star and edited The Communicator. Boston is the author of Inside the Broken California Prison System available at www.Amazon.com, www.humblepress.com and www.fresnoalliance.org. Learn more at www.brokencaliforniaprison.com. To contact Boston, write Boston Woodard, B-88207, 2NB-101, S.Q.S.P., San Quentin, CA 94974.

Dramatic Arts Inside Prisons

In the late 1960s, San Quentin prisoner Rick Cluchey wrote a play called The Cage. After a successful run throughout the country, it was made into Weeds, the movie staring Nick Nolte.

Theater groups have produced plays within the prison system for decades. For example, in the 1980s, a full-fledged production of Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot was performed in San Quentin, sponsored by the Arts in Corrections (AIC) program. In the mid-1980s, Arts Coordinator Jim Carlson brought in a Swedish director, Jan Jonson, who trained prisoner/actors involved in the AIC, including Spoon Jackson (www.spoonjackson.com), who played the pretentious Pozzo. Jonson produced the play under the auspices of Beckett himself from his home in France.

The Waiting for Godot audiences included San Quentin prisoners, as well as visitors brought into the prison from around the San Francisco Bay Area. The production was written and talked about internationally for years.

Today, the San Quentin Shakespeare group (www.MarinShakespeare.org) consists of 12 prisoner/performers. The program was started 10 years ago by Lesley Currier, co-director of the Marin Shakespeare Company, and is taught by Suraya Keating, a professional drama therapist.

Currier and Keating work as a team while directing the plays at San Quentin. Dr. Emily Sloanpace acts as the dramaturge for the Shakespeare productions at San Quentin, explaining the language, scenes and logistics of the play to the group of performers.

San Quentin actor JulianGlenn Padgett played Hamlet last year and was Shylock in this year’s production of The Merchant of Venice. Reflecting on the experience, he said, “For me, acting opens doors to other worlds that are as imaginative as they are complex.”