By Boston Woodard

A reform movement is taking hold in the country. It’s called “justice reinvestment,” and it aims to harvest the billions spent on incarceration and redirect the money to social service programs that might remove the root causes of lawless behavior. According to Alison Shames of the Vera Institute of Justice (VIJ), “The future of the Justice Reinvestment Initiative looks bright, with President Obama including $85 billion for this effort in his proposed 2014 budget, an increase of $79 million over last year’s appropriation.”

In 2003, Susan Tucker and Eric Cadora coined the term justice reinvestment in a policy paper published by the Open Society Institute (OSI). The OSI said the goal was to reduce the billions in prison spending and spend it instead “rebuilding the human resources and physical infrastructure—the schools, healthcare facilities, parks and public spaces—of neighborhoods devastated by high levels of incarceration.” The U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ), the Bureau of Justice Assistance (BJA) and the Public Safety Performance Project of the Pew Center on the States are cosponsors of the Justice Reinvestment Initiative (JRI).

Support

The JRI provides technical assistance and financial support to states, counties, cities and tribal authorities that seek to reform their criminal justice systems using a data-driven approach. So far, more than a dozen states are participating in the JRI. The VIJ, as well as other research organizations such as the Council of State Governments and the Pew Charitable Trusts, help these states study the factors contributing to high prison populations and devise cost-effective ways of reducing them without endangering public safety. Since 2003, the amount spent on prisons has increased.

The JRI provides technical assistance and financial support to states, counties, cities and tribal authorities that seek to reform their criminal justice systems using a data-driven approach. So far, more than a dozen states are participating in the JRI. The VIJ, as well as other research organizations such as the Council of State Governments and the Pew Charitable Trusts, help these states study the factors contributing to high prison populations and devise cost-effective ways of reducing them without endangering public safety. Since 2003, the amount spent on prisons has increased.

In mid-August, U.S. Attorney General Eric Holder said the United States now spends $85 billion annually on incarceration. Supporters say justice reinvestment has helped stop the consistent steady rise in imprisonment. Critics say the movement has not gone far enough, noting that the prisoner numbers have fallen only slowly despite a precipitous decrease in the crime rate. “The U.S. prison population dropped last year by 27,770 inmates, or 1.7%. The total still exceeds 2 million if local and state juvenile facilities are included,” according to the Crime Report.

The VIJ highlighted the views of Don Spector, executive director of the nonprofit Prison Law Office, who challenged poor conditions, including overcrowding, that ultimately led to Brown v. Plata, the landmark case involving California prison overcrowding. Although the VIJ reports that realignment gave the counties virtually unlimited discretion to reform their own criminal justice system, it left them free to develop cost-effective evidence-based programs or to continue their reliance on incarceration.

“What realignment didn’t do is address the underlying causes that led to prison overcrowding,” Spector said. “The Governor’s and legislature’s decision not to change the length of any sentences means that the number of offenders incarcerated will not abate.”

Statistics

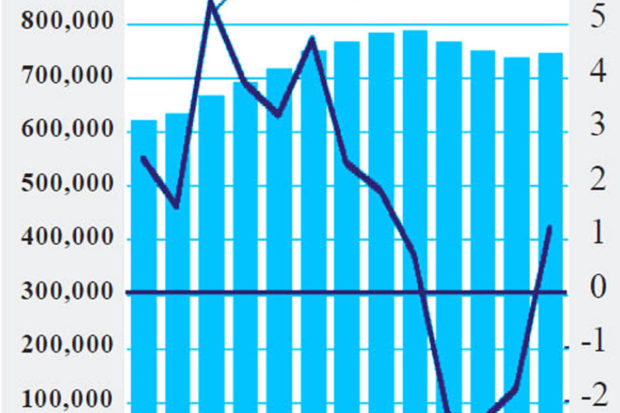

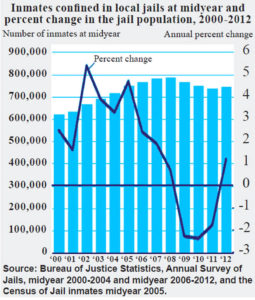

However, DOJ statistics report an increase in California’s county jail population from mid-2011 to mid-2012 by 8,923 prisoners as a result of legislation passed to implement the state’s realignment program. During this same period, national jail populations “remained relatively stable.”

According to the Crime Report, a little more than half the total national decline in prison population since 2011 occurred because of California’s “realignment” plan. However, this “decline” is somewhat misleading. Rather than lowering overall imprisonment rates, California’s realignment plan simply transferred prisoners to local jails.

When the cost of the subsidy to counties is calculated into the equation, neither savings nor reduced incarceration actually occurred. All of California’s 58 counties were given additional funding to deal with the increased correctional population and responsibility, however, each county must develop a plan for custody and post-custody that best serves the needs of the county. After record low jail populations in 2010 and 2011, the California jail population increased in 2012 by an estimated 7,600 prisoners from 2011, according to the U.S. Office of Justice Statistics.

Nationally, the concept of justice reinvestment has garnered a fair degree of bipartisan support, according to Todd R. Clear of Rutgers University, adding, “Reducing mass incarceration is an idea that appeals to the left; reducing the costs of government is an idea that appeals to the right.”

Delaware has made significant improvements in the operation of its criminal justice system. In 2011, Governor Jack Markell established the Delaware Justice Reinvestment Task Force to conduct a comprehensive examination of the factors contributing to the size of the corrections population, both pretrial and sentenced individuals. The VIJ aided Delaware’s task force by analyzing “who was coming to prison, why were they committed, how much time they receive[d], and what sort of program participation they were involved with.”

The task force found that people awaiting trial made up a large portion of the jailed population. Other factors included supervision practices that resulted in a large number of parolees returning to prison and long sentences with limited opportunities for prisoners to earn reductions—even when the prisoners had made significant steps toward rehabilitation.

The VIJ’s Web site states that, despite California’s prison realignment program being less than effective, some counties such as “San Francisco continue to find new ways to reduce recidivism and lower jail populations through successful alternatives to incarceration.” However, the VIJ noted that other California counties continue the failed policies of the state by overcrowding their jails and, in the process, “deprive prisoners of their right to be free from the cruel and unusual conditions the Supreme Court recently condemned.”

According to the BJA, state prison populations fell in nine states using the justice reinvestment strategy. However, California is not part of the justice reinvestment program.

The JRI process has encouraged states to identify and realize savings through reduced corrections and justice system spending. Those savings result from a number of reforms, including reducing prison operating costs, averting spending on new prison construction and streamlining justice system operations.

North and South Carolina have both reported substantial savings in adopting the reinvestment approach. The critics say California needs to join the trend. Christopher Nelson, writing on realignment in August, said, “Without state mandates on exactly how to implement AB 109, counties are free to embrace old world ideologies with the AB 109 funding they are given (e.g., hiring more law enforcement rather than exploring evidence-based programs).”

Two years into the realignment program, many California counties “are without significant data collected or interagency cooperation forged to ensure the success of such a massive undertaking,” said Nelson. According to Spector, this indefensible situation “calls for the creation of a public safety commission to devise a sentencing scheme that is based on data, risk, proven practices and available resources.”

Two years into the realignment program, many California counties “are without significant data collected or interagency cooperation forged to ensure the success of such a massive undertaking,” said Nelson. According to Spector, this indefensible situation “calls for the creation of a public safety commission to devise a sentencing scheme that is based on data, risk, proven practices and available resources.”

“It’s not just a matter of the right and left hand not talking, it’s 10 fingers operating independently and without knowledge of each other. That is not a recipe for success,” said Spector.

Professor Clear said criminologists seem content to study and lament the origins of mass incarceration but not to orchestrate its demise. “My fear—or more directly my observation—is that criminologists have little training in such matters and have little to offer policy makers and the public for how to get it done. It is like establishing a Manhattan-type project on how to reduce imprisonment with no scientists to build the decarceration bomb.”

Mark A.R. Kleiman of UCLA says the proposition of “justice reinvestment is attractive on the surface.” He argues that if money spent on bringing down crime via incarceration “could prevent just as much crime, or even more crime, if spent some other way, then why not do so?”

Kleiman said that if the “budget mechanism” is defective, not able to put saving into financial support for programs replacing prisons, then what needs to be done is to change the budget mechanism. This change would be “justice reinvestment as a policy, rather than merely as a slogan,” said Kleiman.

For more information on JRI, visit http://ojp.usdoj.gov/BJA/JRI or e-mail justicereinvestment@urban.org.

*****

Boston Woodard is a prisoner/journalist. He writes for the Community Alliance and the San Quentin News, has written for the Soledad Star and edited The Communicator. Boston is the author of Inside the Broken California Prison System, which is available at www.amazon.com. Learn more at www.brokencaliforniaprison.com. Contact him at Boston Woodard, B-88207, 2-N-1O1, S.Q.S.P., San Quentin, CA 94974.