During World War II, more than 100,000 Japanese Americans were taken by U.S. authorities and placed in concentration camps around the country. The government argued that these Japanese Amercans might act in solidarity with the land of their ancestors, perhaps as spies or conducting acts of sabotage. Neither accusation was ever proved. Yet, entire families were sent to the camps for years, in many cases losing all of their property and valuables.

All U.S. institutions supported this behavior, including the Supreme Court, and the few voices opposing it were either silenced or ignored.

The “Other” Incarcerated Japanese

While the incarceration of Japanese descendants in the United States was outrageous, the kidnapping and detention of Japanese abroad was a bizarre, illegal and immoral act of imperial arrogance by the United States.

More than 2,300 people of Japanese origin residing outside the United States were kidnapped and sent to concentration camps in the United States. More than 80% of them were from Peru.

The Japanese immigration to Peru started in the early 1900s. Hundreds of men crossed the ocean looking for a better future. They worked hard, started businesses and built families.

But little did they know somebody was watching them. And when WWII started, they became targeted by the United States.

Washington lobbied most Latin American countries to cooperate with a plan of “controlling” citizens or descendants of immigrants belonging to countries at war with the United States and the Allies: Germany, Italy and Japan, the “Axis Powers.” The plan included the arrest of some of them and sending them to the United States.

Although this plan started in Panama, Peru was hit the hardest as it had the largest Japanese community in Latin America. In Peru, discrimination and racism against Japanese was rampant. By the mid-1930s, the country prohibited immigration from Japan and later prohibited all Japanese newcomers from becoming Peruvian citizens. During the 1940s, several businesses owned by Japanese descendants were attacked, as well as some individuals.

This racist environment helped the United States plan to arrest Japanese in Peru and ship them to concentration camps.

The United States knew that aspects of the war were being fought in Latin America too, so it pressured those countries to join a security agreement, which was controlled by the United States. This agreement included the arrest of “suspicious” individuals (and their descendants) from countries at war with the United States. This agreement framed the “legality” of the U.S. espionage and the arrests of suspected individuals.

The Latin American countries that cooperated were Bolivia, Colombia, Costa Rica, Ecuador, El Salvador, Guatemala, Haiti, Honduras, Nicaragua, Panama, Peru and the Dominican Republic.

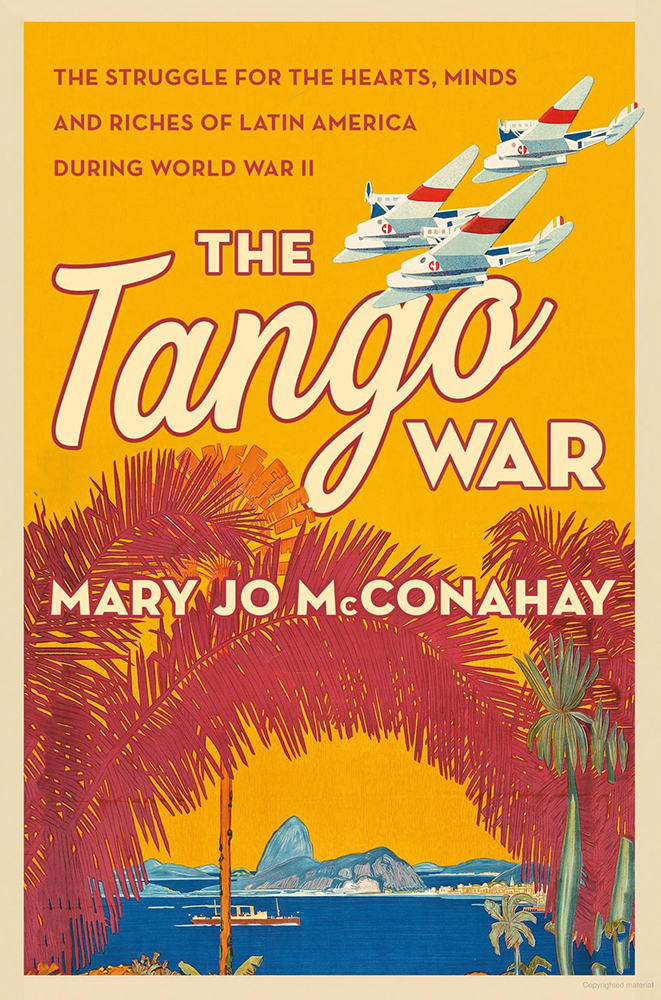

“When I was living in Guatemala, I heard stories about Germans being taken and sent to the U.S. during WWII. Later, I also heard about Japanese from other Latin American countries going through the same experience,” said Mary Jo McConahay, a journalist from the Bay Area and author of a well-documented book about how the United States “fought” WWII in Latin America, a war that involved the kidnapping of Germans, Italians and Japanese. The Tango War is a must read to understand this little-known aspect of modern U.S. history.

“The Japanese in Latin America, mostly from Peru, were kidnapped by the State Department, Special War Problems Division, under a secret program called Quiet Passages,” said McConahay.

“It was a program to forcibly capture people with the justification that ‘we don’t need a fifth column.’ Besides, Latin America was an important area of resources for countries involved in WWII (minerals, food, etc.), and they didn’t want the ‘Axis’ to put their hands on them.

“In such a context, the U.S. government was concerned about the Japanese spying on behalf of their original land. There was no evidence of this, and worst of all, they didn’t even have connections with Japan.

“That was the ‘reason’ to justify the kidnappings. But the real reason was that Germans and Japanese were good ‘customers.’ Some of them were prominent members of their communities and successful entrepreneurs. The U.S. was thinking not only of crippling their trade but [also] of taking over the trade.”

After the Pearl Harbor attack, Peru severed diplomatic relations with the Axis—Germany, Italy and Japan—and ordered some Japanese community leaders to be arrested. The list was prepared by U.S. intelligence. The United States compensated Peru with military assistance and opened a military base there. Even more, the Peruvian government closed Japanese schools and newspapers.

Those arrested were sent to the United States by vessels on trips that could last weeks. Upon arrival, they were stripped of their documents, interrogated, sprayed with DDT and sent to a concentration camp.

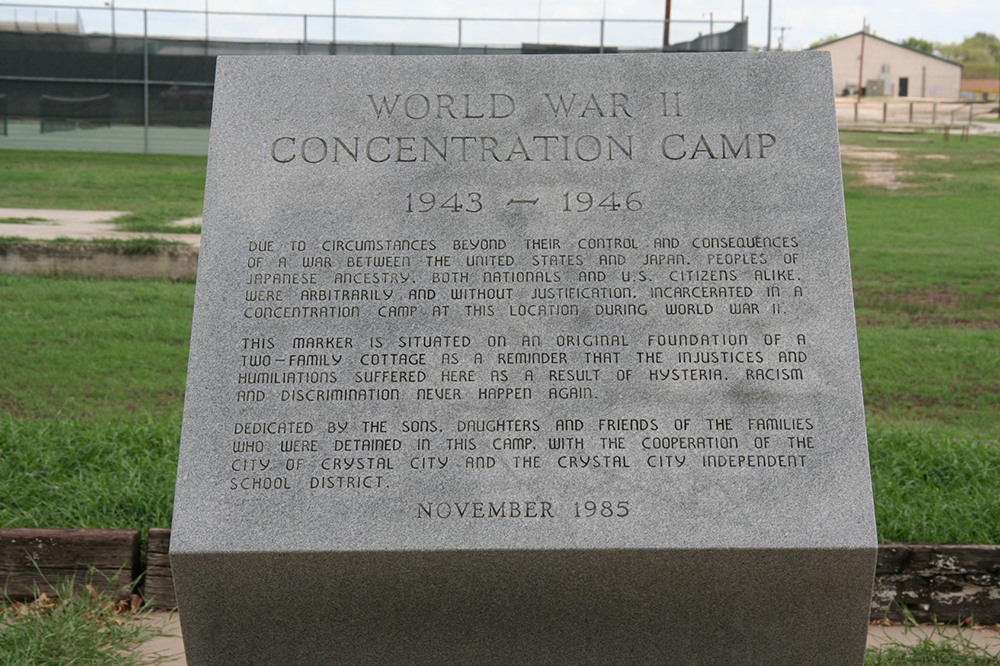

Most Japanese from Latin America were sent to the Crystal City camp in Texas, a former labor camp that housed Mexican braceros harvesting spinach. The living conditions were deplorable; in some cases, 80 people shared a small barrack with only one bathroom. The Japanese were separated from detained Germans.

Although the State Department justified these incarcerations as part of national security, in fact Washington wanted to have enough Japanese detainees to trade them for American prisoners held by Japan. By 1942, the State Department estimated that 3,300 Americans were under Japanese control in Asia. By the same year, more than 1,000 Latin American Japanese were sent to Japan as part of a prisoner exchange.

“Quiet Passages was a program dedicated to getting Japanese people in order to exchange them with U.S. prisoners. They needed Japanese,” explained McConahay.

“Japanese Americans were [deemed not appropriate] for this trade—and they were incarcerated already. So they needed ‘other’ Japanese. And they found them in Latin America, particularly in Peru.

“They were taken out of their houses, off the streets…There was opposition, there were voices of resistance to this program within the U.S. government, people who thought ‘this is not right, it doesn’t seem legal—or at least ethical.’ But they were silenced.

“There was also a racist component to this plan. The U.S. always considered Latin America as ‘our backyard.’” So Washington didn’t care much about potential criticism from south of the border.

“The Peruvian Japanese were taken on fishing vessels—some belonging to an Alaskan fishing company,” said McConahay. “Because of the war, the U.S. government was able to take these types of vessels. These were not luxurious ships, but smelly, overcrowded vessels.

“And daily life at the camp in Texas was very difficult. Red ants, alacrans, roll calls three times a day…

“One testimony of an incarcerated person at the Crystal City camp mentioned that one time he helped place the body of a dead man outside the camp. Ironically, he stated, ‘it was weird the feeling of freedom thanks to a dead person.’”

Not All Countries Cooperated

“The Peruvian government was willing to cooperate with the United States, however other governments didn’t,” noted McConahay. “Mexico, under Avila Camacho, refused to cooperate with the United States. And no military bases were established there.

“I talked to some Mexicans of Japanese origin who are still thankful for this. However, the Mexican government removed Japanese people from the Pacific Coast and from the U.S.-Mexico border.

“Argentina didn’t cooperate either. I am not sure if the Argentinian government was approached by Washington. However, Juan Peron was the president at that time and he had fascist sympathy.”

The War Is Over

When the war was over, in 1945, the United States didn’t know what to do with the incarcerated Latin American Japanese. Peru didn’t want them. After long negotiations, some were sent to Japan and a handful back to Peru.

Before the end of the war, a group of about 300 Japanese were sent to work at a labor camp in New Jersey. Even though the working conditions were bad, they were free at least, and they were getting paid.

It wasn’t until 1953 when the State Department—without options—accepted to grant residency to those Japanese from Latin America who were left in the country.

In the 1980s, the U.S. government recognized its responsibility for the incarceration of the Japanese Americans during the war and issued an apology and compensation. However, the Latin American Japanese were not included in this reparation.

Illegally Kidnapping Foreign Citizens

The excuse of protecting the country from foreign attacks is continuously used by the United States to pursue aggressive militaristic behavior. After the 9/11 attack, the George W. Bush administration implemented a program of kidnapping foreign citizens around the world. Those citizens, suspected of “terrorist activity,” were sent to the United States and later to the Guantanamo base. Some remain in captivity, with no charges or procedure to clarify their legal situation. They just were classified as “terrorists.”

The invasion of Iraq, as revenge for the 9/11 attack, was completely illegal. It is suspicious why the International Court of Justice doesn’t charge any president of the United States as a war criminal.

The fact that during WWII and after the 9/11 attack illegal kidnapping took place around the world is a delicate and complicated issue that U.S. activists should alert our society about.

No country should be above international law. No citizen of any country should fear for their safety regardless of their political opinion.