BY MATTHEW ARI JENDIAN, SIMON BIASELL, JIM GRANT AND AKIKO MIYAKE-STONER

Been in Fresno long? Ever notice how the city has grown (mostly northward) and what has happened in the wake of that growth (mostly neglect and urban decay of the older parts of Fresno)?

Unchecked outward growth has led to significant negative impacts in the heart of Fresno. Physical decay, blight, vacant lots, fires and crumbling infrastructure in our urban core are blatant, visual examples of those impacts, while residents are also facing unseen impacts of worsening air quality, overcrowding and increased poverty rates.

Where did it all begin?

In 1872, the City of Fresno was established, coinciding with a train depot at Tulare and H streets. East of the tracks was the city center where homesteaders resided, and west of the tracks was home to Chinese immigrants who settled there after the gold rush. The railroad marks the first east/west divide of Fresno and divide of race and class, demarking West Fresno as the “center of vice.” Fresno became the county seat in 1874 and was incorporated in 1885.

Got plans?

Every city plans how it’s going to grow, and Fresno’s first General Plan in 1918 upheld the east/west divide of Fresno and established southeast Fresno as an “industrial area.” Due to the negative effects of the Great Depression, President Roosevelt initiated the New Deal and Congress created the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC) in 1933 and the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) in 1934 to help refinance home mortgages currently in default to prevent foreclosure as well as expand homeownership.

HOLC examiners consulted with local bank loan officers, city officials, appraisers and realtors to create color-coded “Residential Security” maps of cities that categorized the riskiness of lending to households in different neighborhoods: green for the “Best,” blue for “Still Desirable,” yellow for “Definitely Declining” and red for “Hazardous,” further influencing the development of north Fresno under the guise of “economic development.”

By the 1950s, at the height of the Cold War, a former member of the Fresno County Board of Supervisors would refer to Highway 99 and the railroad tracks as “Fresno’s Berlin Wall.”

In the decades that followed, city plans and zoning ordinances kept southwest Fresno isolated. City leaders concentrated wealth and development farther north, catering to its affluent white neighborhoods. There, the shopping malls, hospitals and college campuses were built, while southwest Fresno got slaughterhouses and meatpacking plants.

According to Richard Rothstein, author of The Color of Law, the geographic, economic and racial isolation of a city’s black and brown residents is a pattern duplicated across the country thanks to government policies.

Today, some argue that Shaw Avenue or even Herndon Avenue has replaced the railroad tracks as the city’s dividing line. White and wealthy above to the north; poor, black and Hispanic to the south. A 1970s-era city planning document referred to Shaw Avenue as Fresno’s “Mason-Dixon Line.”

Doubling Down in the Wrong Direction

In 1973, when the City of Fresno was updating its General Plan, a 24-member General Plan Citizens Committee was established. The City’s planning department developed four general plan alternatives, and the Citizens Committee developed Alternative 5: Growth focused on densification around Blackstone Avenue, which would increase access while containing development to the already urbanized areas.

“Subject to environmental review under the California Environmental Quality Act of 1970 (CEQA), Alternatives 1 and 5 were concluded to have the best impact on the physical and social environments of the city.” Yet, despite a favorable environmental assessment and protest from the Citizens Committee, neighborhood council members and the general public, the City Council adopted Alternative 4 in favor of urban growth, which has led to “suburbanization,” “sprawl” and continued divestment from southwest and southeast Fresno, in favor of investment in north Fresno.

Not Again, Not on Our Watch

With some community organizing around development, the City of Fresno adopted a new General Plan in 2002, seeking to “reach a balance between the outward growth pressures and downtown revitalization. The plan directed 80% of growth inside of the city’s existing boundaries and the remaining 20% of population growth would be accommodated into the two expansions of the urban boundary—North to accommodate the upscale Copper River development and Southeast to a new town concept, that would (ultimately) be designed for higher densities and ‘green style’ living.”

More community organizing centered on development followed the adoption of the General Plan, including Fresno Works for Better Health, the Central Valley Air Quality Coalition, Faith in Community (PICO), the Fresno Housing Alliance and Concerned Citizens of West Fresno, among others, from 2003 to 2005.

Several more social justice organizations formed or increased their organizing regarding development from 2010 to 2013 and later in response to concerns about housing evictions during the Covid-19 pandemic, including Building Health Communities (Fresno BHC), the Fresno chapter of the ACLU, Communities for a New California, the Central Valley Partnership, Central California Legal Services and Leadership Counsel for Justice and Accountability.

In 2014, after a series of charettes gathering public input and community organizing, the Fresno City Council updated the General Plan to create “a balanced city with an appropriate proportion of its growth and reinvestment focused on the central core, Downtown, established neighborhoods, and along Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) corridors.” The update also specified that “a successful and vibrant Downtown is necessary to attract investment needed for infill development and rehabilitation of established neighborhoods, which are priorities for the Plan.”

Although a community-supported General Plan was adopted, the civic muscle was not yet in place to ensure systematic implementation and hold City officials accountable.

With more recent additions of Fresno DRIVE and the Fresno Opportunity Corridors, the Fresno Community and Economic Development Partnership (Fresno CEDP) representing citizens across Fresno through 16 organizations (Jane Addams CDC, Better Blackstone Association, Chinatown Fresno, Downtown Fresno Partnership, El Dorado Park CDC, Every Neighborhood Partnership, Fresno Area Community Enterprises, Hidalgo CDC, Highway City CDC, Jackson CDC, Lowell CDC, Southeast Fresno Community & Economic Development, Saints Rest Community Economic Development Corporation, Southwest Fresno Economic Development, South Tower Community Land Trust and Tower Neighborhood Association), the Central Valley Industrial Areas Foundation (IAF) and the Greenfield Coalition, the civic muscle of Fresno is being developed and exercised as a countervailing force, altering the dynamics of power in the City of Fresno.

The Community Engagement to Ownership Spectrum, created by the Facilitating Power & Movement Strategy Center, visually captures the pathway toward greater racial, economic and environmental justice through the shift from community engagement to community ownership, referencing Arnstein’s Ladder of Citizen Participation, the International Association of Public Participation’s Spectrum of Public Participation, and the work of grassroots organizing and advocacy groups working to hold local systems accountable to the public.

A New Clovis, Southeast of Fresno?

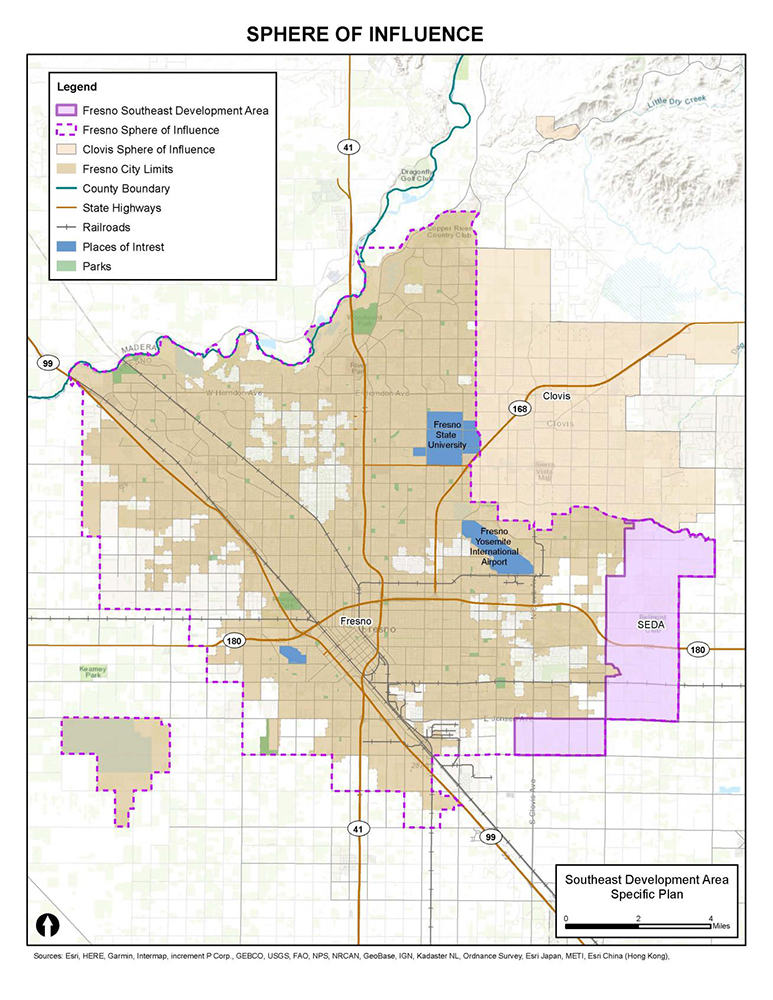

Before year’s end, Fresno Mayor Jerry Dyer’s administration is requesting the Fresno City Council’s approval of the transformation of nearly 9,000 unincorporated acres—16 times the size of the Copper River Project in northeast Fresno and seven times the size of Riverstone and Tesoro Viejo in Madera—southeast of Fresno into a new Clovis on Fancher Creek.

The project, known as the Southeast Development Area (SEDA), requires the City to annex the land, and it is expected to result in 45,000 homes housing 135,000 people on former farmland and rural homesteads.

For existing property owners in that area, annexation would result in higher property taxes and unplanned costs associated with requirements to connect with the City’s water and sewer infrastructure. Annexed property owners will also feel a loss of autonomy as they would come across new zoning laws, building codes or other regulations they had not previously experienced.

The City of Fresno would have to borrow more than $3 billion to advance the urban public infrastructure required to develop SEDA as proposed, which would inhibit the City’s ability to invest in the existing parts of Fresno, which have already-existing infrastructure needs. SEDA would also require 16 new schools in the Sanger Unified School District, costing more than $1 billion. Increasing developer fees to help cover this cost from $4.75/square foot would be required, but that has not become part of the City’s proposal.

The current iteration of SEDA is based on out-of-date population projections—overstating demand for the project by not reflecting dramatic reductions in future population growth projected by the California Department of Finance. California’s statewide population is expected to plateau at its current level through 2060.

When the baseline data for the General Plan update in 2014 was being prepared, Fresno County was projected to have a population of 1.9 million in 2050. However, recent state projections suggest Fresno County will only grow at a rate of 0.2% annually to 1.095 million people by 2060, falling well short of making SEDA necessary to meet any housing or other population growth related needs over the next four decades, all which now can easily be met within the existing city limits.

Of the 63,000 acres already within Fresno city limits, approximately 8,700 acres (14%) are vacant (undeveloped land) with the zoned capacity to hold more than 134,000 housing units.

In addition, the environmental impacts from SEDA include a 25% increase of the city’s greenhouse gas footprint and a 600% increase in air pollution emissions in southeast Fresno, yet no mitigation fees have been incorporated into the City’s plan. We do not yet know what impact this will have on public health because the City of Fresno did not investigate that in its environmental review.

What You Can Do

The Greenfield Coalition is a group of residents and leaders committed to revitalizing our urban core, preserving Fresno’s agricultural land and green spaces, and advocating for responsible growth and urban planning. In August 2023, the Greenfield Coalition released an independent study by ECONorthwest to analyze the impacts of fringe development on the urban core.

The Fresno Urban Decay Analysis gives an overview of Fresno’s history, defines “urban decay” and its measurement factors in the economic and social context of Fresno, and uses interactive data and historical mapping to show urban decay in five focus neighborhoods: Blackstone, Kings Canyon/Ventura, Hidalgo, Downtown and Southwest Fresno.

Fresno has a long history of supporting development and greenfield annexation on the edges of our city. For decades, city leaders have prioritized developer interests and greenlit subdivisions on the city’s edges with shiny promises of new housing, safety and the American dream, but this unchecked outward growth has led to significant negative impacts in the heart of our city.

*****

Matthew Ari Jendian, Ph.D., is a professor of sociology at Fresno State; Rev. Simon Biasell is the pastor of the Big Red Church; Jim Grant is a member of St. Paul Newman Catholic Center; and Rev. Akiko Miyake-Stoner is an ordained elder of the United Methodist Church.

Take Action!

Join the Greenfield Coalition (greenfieldcoalition.org/), a group of residents and leaders committed to revitalizing the city of Fresno’s urban core, and consider the following actions:

- Contact the Fresno Mayor’s Office: fresno.gov/mayor/

- Contact your Fresno City Council Member: fresno.gov/citycouncil/

- Attend the following public meetings and add your voice to the conversation:

- Dec. 6, 6 p.m.: The City of Fresno Planning Commission will hold a public hearing on the SEDA (Southeast Development Area) draft specific plan and Environmental Impact Report (EIR). Individual public comment of 2–3 minutes will be allowed. The Planning Commission will then make its recommendation to the Fresno City Council.

- Dec. 14: The Greenfield Coalition has requested that the Fresno City Council meet at 6 p.m., with SEDA as the sole agenda item to allow for a public hearing. The City Council will decide on the SEDA plan/EIR.