In Japan, earthquake-born tidal waves engulfed backup safety systems at the Fukushima reactor complex. Half a world away in Madera County, local officials were giving their unanimous support for plans to build nuclear reactors in the San Joaquin Valley. Never mind the reactor core meltdowns and airborne radiation. Never mind the seawater and soil contamination. Never mind the state moratorium on new nuclear power plants. Nothing was going to deter the hard-charging Fresno Nuclear Energy Group LLC from bringing its nuclear dreams to fruition. In fact, it is doubling down on the bet.

Despite the tragic nuclear nightmare unfolding before everyone on the worldwide media, Fresno Nuclear is pushing harder than ever to build two 1,600-megawatt reactors somewhere on the west side. But questions persist about the feasibility and safety of nuclear power in general, and about the particular reactor system being proposed. But between the dream and its realization, there is a large barrier of inconvenient truths to overcome.

We’re told a renaissance of the nuclear age is upon us. It’s called the EPR, or European pressurized reactor. Perhaps in an attempt for sexier branding, it is now being marketed as the evolutionary pressurized reactor. But whatever the name may be, it is a tough sell and getting tougher. It is built by the French company Areva, which is on a global building spree with its latest generation reactor. At least that’s what is intended.

According to an industry publication, Nuclear N-Former, the U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) in April wrote Areva a letter stating the EPR reactor has yet to prove that it meets U.S. design-safety standards. The NRC’s Scott Burnell said, “There are areas where the staff simply cannot accept Areva’s approach.”

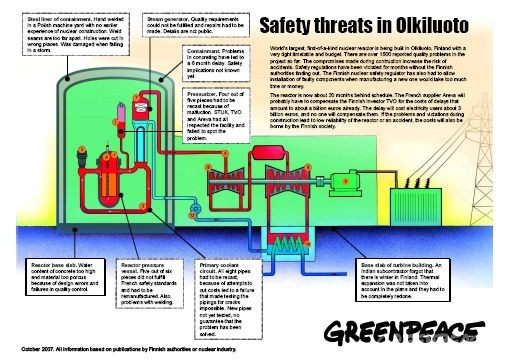

This letter comes in the wake of problems with the EPR discovered by regulators in Europe. Nuclear safety officials in France, Finland and the United Kingdom have jointly asked Areva to make changes to the reactor’s control and instrumentation systems. They want safety systems separated from control systems, so that a simultaneous failure would not result in an emergency situation—something Areva’s designers apparently didn’t take into account. It is this and other problems with the EPR that are now creating a meltdown for Areva and the French nuclear industry.

In Olkiluoto, Finland construction of an EPR is facing delays over faulty pipe welding and other issues. The Electricity Forum stated in its April 2011 issue that Areva expects to lose more than $4 billion on the project, “Olkiluoto was meant to showcase the EPR to the world, but has become a high-profile disaster that is running three years late.”

Flamanville, a pastoral resort town on the Atlantic coast of France, is the scene of another Areva EPR project with cost overruns and construction issues. French union officials said last July that the project is at least two years behind and nearly two billion Euros over budget. Industry journal Nucleonics Week cited a number of problems with welds in the steel liner of the containment building and errors in the installation of steel reinforcement. That’s only the beginning!

Confidential documents disclosed by an anonymous whistleblower from EDF, the major power company in France, reveal a literally explosive possibility. The International Institute of Concern for Public Health reported on June 13, 2010, that documents revealed by the French watchdog group Sortir du Nucleaire “show that the design of the EPR presents a serious risk of a major nuclear accident – a risk deliberately taken by EDF to increase its profitability.” The scenario, according to the documents, is that some operating modes could cause the reactor to explode because of an accidental ejection of a control rod cluster.” The report concludes that the EDF and Areva have tried but failed to find a solution to the operating mode problem, which increases the risk of a Chernobyl-type accident with the EPR design.

More bad news for Areva and the French nuclear industry came from Stephen Thomas, an economist and energy analyst at Greenwich University in England. In a 2010 study, Thomas concluded that construction of the two EPR reactors in Europe has “gone dramatically wrong from the beginning” despite EDF being the most experienced nuclear utility in the world. The report suggests the problem is not with experience but with the “build-ability of the design itself.” Because design problems lead to construction problems and drive up the cost of electricity, Thomas says it will make the price of EPR power unaffordable except where huge public subsidies are offered.

Prospects for Areva, EDF and the EPR reactor might be dimming in the United States as well. In Maryland, even with a massive taxpayer subsidy, the EPR reactor is not a good enough deal. Baltimore-based Constellation Energy recently pulled out of a joint venture with EDF to build an EPR reactor complex at Calvert Cliffs, on Chesapeake Bay. Constellation, financially on the ropes, decided that a $7.5 billion loan from the U.S. Department of Energy “is unreasonably burdensome and would create unacceptable risks for our company.” Now the project is in a bind because EDF is the only player left and U.S. law does not allow a nuclear power plant to be owned by a foreign entity.

Fresno Nuclear CEO John Hutson’s bullish view of nuclear power is undimmed by the messy track record of the EPR. He vigorously advocates that nuclear energy is a critical part of the effort to combat global climate change, along with wind and solar. Vigorously enough to convince some of Fresno’s major business and political players to go along. Last spring, he brought Areva CEO Anne Lauvergeon to kick-start a public campaign. Back then, it was all about providing cheap, clean, safe power to Fresno. Somewhere along the way, it has morphed into a different kind of project.

To get around the moratorium on nuclear power plants, Fresno Nuclear is now packaging the project as a “water treatment” facility. The plan is ambitious and even Hutson says “it may sound like pie in the sky.” He estimates it will cost $5 billion, claiming it will all come from the private sector without any federal loan guarantee.

Pointing out that there is an ocean of water a mile or two under the Valley, Hutson declares that “we have all the water we need. It just has salt in it.” His solution is to pump the water from the underground aquifer and use heat, generated by electricity, to separate the salts. He’s counting on two products that can be sold on the market—water and products made from the salts.

Why nukes? Hutson says power from the grid is too expensive for such a process and solar does not provide sufficient power. He figures the plant could produce enough clean water, priced at $350 an acre-foot (126,000 gallons), to expand Valley agriculture by 40,000 acres and boost employment. Will it work? According to water analyst Lloyd Carter, west-side farmers are currently paying about $100 per acre-foot for surface water deliveries. He thinks Hutson’s price point is far above what is affordable for farming in the long term. So, will the water be sold to Los Angeles or Tejon Ranch? Hutson insists that “this is a Valley project.”

Beneficial as such a vision might be for the Valley economy, it all comes back to the lynchpin of the scheme—the EPR nuclear reactor. Hutson is ebullient in his confidence that it will all work out.

What about Finland and France? Hutson says Areva is learning lessons from those problems, “Those things are an advantage to Fresno because they’re going to have those things figured out.”

What about containment safety? Hutson describes the reactor vessel’s thick double wall design as “missile-proof, bomb-proof, nothing gets in, nothing gets out.”

And a potential meltdown accident with a control rod cluster ejection? Hutson insists it can’t happen, “I don’t see how it could.”

The reactor design, he says, is much safer because the coolant system operates on gravity and convection currents, which can operate “for a heck of a long time” without having a power-operated pumping system, which was the critical breakdown at the Fukushima complex.

Another issue will be spent fuel from the reactor. Hutson is speculating that it will be returned to France for recycling. The problem is France does not accept nuclear waste from other countries—yet another inconvenient truth. Hutson believes that the criticism of the EPR is in the eye of the beholder, “Facts don’t dominate, fear does.”

Perhaps the major concern for nuclear power anywhere is earthquake damage. Although the Valley is not the most earthquake-prone region of the state, they do happen here. The most noteworthy one in recent times happened on a fault on the Valley’s west side that badly damaged the city of Coalinga. It registered magnitude 6.0 to 6.5 on the Richter scale.

Dr. Stephen Lewis, a professor in the Earth and Environmental Sciences Department at Fresno State, says such an earthquake could be expected again. If it did occur, the ground shaking could affect a reactor building in that area. According to Dr. Lewis, the severity of earthquakes depends on three factors: magnitude, distance from the epicenter and local soil conditions. In some areas, Valley topsoil is vulnerable to ground shaking emanating from a fault slip.

Then there is the storied San Andreas fault, not far from the Valley and capable of generating earthquake magnitudes in the 8.0 to 8.2 range. Dr. Lewis thinks an earthquake of that magnitude “can produce pretty significant ground shaking.”

Potentially the real sleeping giant is the Cascadia Subduction Zone. That’s where the Eastern Pacific tectonic plate dives under the North American plate. The last time it slipped was 1700 ad. Scientists at the U.S. Geological Survey found that the event was between magnitude 9.0 and 9.5, and not only had a massive impact on the Pacific Northwest but also caused a major tsunami in Japan. Dr. Lewis believes such a tectonic event “would produce ground shaking in the Valley of the same intensity as the 1906 San Francisco earthquake.”

Given the manifold problems facing this project, critics doubt it will ever be realized. Hutson realizes the big risks involved but figures they are outweighed by the potential benefits. In the final analysis, it’s up to the community as a whole, not a group of private investors, to decide whether going nuclear is an acceptable risk.