It has always been known in Fresno as Chinatown, or the West Side, or the Other Side of the Tracks. But the fading facades of old buildings hide a rich history. If those old walls could talk, they would tell fascinating and even mysterious stories reaching back decades into the past. Many of those stories would tell of the lives of people in the Japanese diaspora to California.

Japanese immigrants formed communities that they called Nihonmachi wherever they settled, each with its own unique character. There were more than 40 Japantowns in the state, stretching from Marysville to San Diego. They were in the urban centers of San Francisco and Los Angeles. They were in the fishing towns along the Pacific coast and the farm towns of the San Joaquin Valley.

Only remnants are left now, but they are symbolic of what Japanese Americans achieved and then lost due to the xenophobia and the winds of war. Struggling against a plethora of obstacles, Japanese Americans forged an indelible and far-reaching presence in California and locally.

Why and how this transpired is the subject of a remarkable project called Lost Kinjo that is dedicated to rediscovering the lost Japantowns of California. It is sponsored by the California Public Library Civil Liberties Project and the Takahashi Family Foundation. Researchers have uncovered historical information about many of the lost Kinjo, publishing a series of articles in the AsAm News.

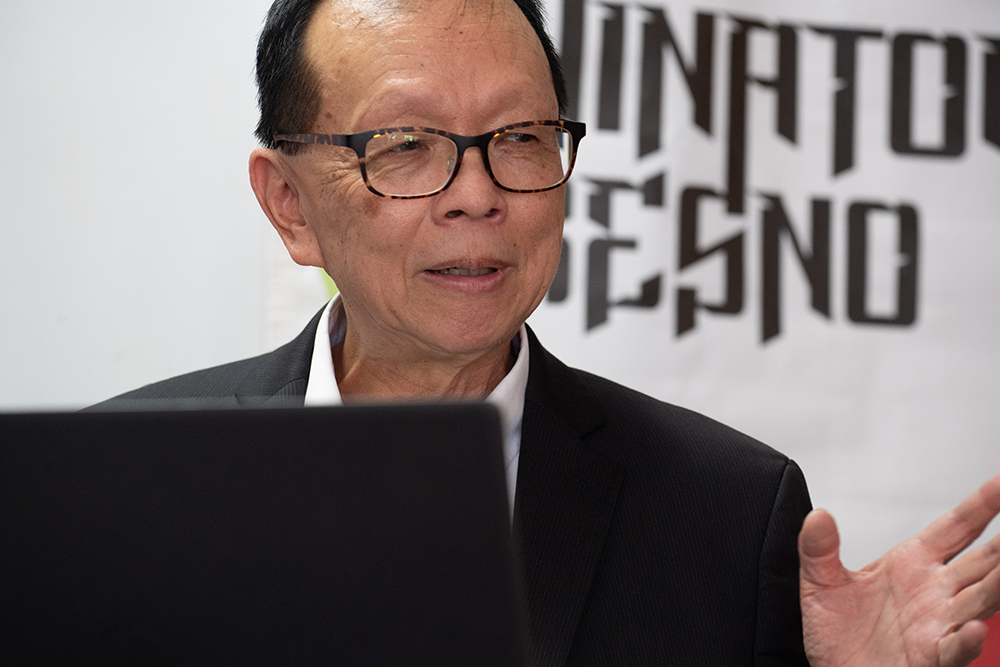

That is what brought Dr. Raymond Douglas Chong to Fresno on a recent warm spring day. One goal of the Lost Kinjo project is to educate and involve local communities in this process of rediscovering our own fascinating Nihonmachi stories that are now lost in the mists of time.

Interestingly, the building where Dr. Chong’s talk was held was built in the 1910s by a man named Hidekima Iwata. It originally was two stories tall, and it is like the other Iwata building across F Street, the still intact Nippon Building.

What drove the establishment of Chinatowns and Japantowns in the late 19th and early 20th centuries was xenophobia and racism. Those emotions ran strong among most of the Caucasian majority population in California.

Along with the surge in Chinese immigration in the mid-1800s to work in gold mines, build railroads, and construct levees in the Bay Delta and other infrastructure, bigotry against them reached a fever pitch. In 1882, the Chinese Exclusion Act restricted immigration from China.

Dr. Chong affirms that this opened the door for Japanese immigration from 1886 to 1924. “They legalized through Hawaii and came ultimately to the mainland. Those who came early were working the sugar and pineapple plantations at that time.

“Once they reached the mainland, they got involved with basically four trades: salmon canneries, lumber, sawmills and mining camps.”

Mostly, it was men who comprised Japanese immigration, whether they were coming from Hawaii or Japan. Dr. Chong described an arrangement concocted by the U.S. government.

“It was largely before 1908 a bachelor society. You would say roughly 95% of the Japanese were men. So, there was the infamous 1907 Gentlemen’s Agreement between President Theodore Roosevelt and the Japanese Empire to limit Japanese labor.

“But there was an escape clause, or a loophole, that allowed you to bring your picture bride based on a photo and have blessed harmony and happiness.

“[However,] the reality is some of these brides, when they came through San Francisco, it was like a toxic reaction. When they met their husband, it was like total shock.

“On the plus side, it created a boom in the Nisei community, the second generation.” The picture bride program was only allowed from 1908 to 1920 because the white power structure saw the growing numbers of Japanese American families as a threat.

The concept of a “red line” to segregate those considered undesirable by the dominant Caucasian society was invented by Bay Area real estate magnate Duncan McDuffie in the early years of the 20th century.

Many of California’s ruling elite were not only racist but also actively involved in the eugenics movement, which sought, in an organized fashion, to eliminate people they considered inferior, which included most varieties of non-WASP (White Anglo-Saxon Protestant) human beings. These were the captains of industry who owned and operated nearly everything of consequence in the West: timberlands, mines, railroads, steamship lines and large swathes of real estate.

It was a made-in-America product that later became the blueprint for Nazi sterilization and extermination programs in Europe.

Fresno was no exception to the practice, and the Southern Pacific railroad tracks became the red line that segregated the city after white landowners pressured the Southern Pacific not to sell or lease land to Chinese and other people of color.

Local ruling elites officially designated that people who had emigrated from these areas could only live west of the railroad tracks: Africa, Armenia, China, Greece, Italy, Japan, Mexico, Philippines, the Basque nation and Volga Russians from Germany. It is sobering today to contemplate such a society.

Legal measures, such as the 1913 California Alien Land Act, were also used to exclude Asians from owning property. Later, they were forbidden to even lease land.

“That was the first white farmer prescription because they realized Japanese farmers were very successful in raising produce,” says Dr. Chong, “in particular, the niche truck crops, as they called them, especially in Los Angeles.”

In the San Joaquin Valley, many Japanese Americans became farmers, whereas others started businesses to serve the expanding Japanese population whose commercial centers were growing inside Fresno’s Chinatown and scattered small towns around the Valley.

Dr. Chong says this was a natural course of action. “Of course, farming is the basis. And the Japanese farmers became very successful. Coming from Japan, they knew how to farm already. So, they were successful with many of the crops.

“And the white growers saw them as competition. They were finding ways to diminish Japanese influence. Imagine over 6,000 farms all through this state, and the size of ownership or leases on 200,000 acres of land.

“And the value at that time of the crops being generated, whether it’s vegetables or fruits or nuts, in 1942, was roughly $73 million. So, this was the magnitude of the consequences before the concentration camps of 1942 to 1945.”

In 1922, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that Takeo Ozawa, a 20-year resident, could not become a naturalized citizen of the United States because he was not Caucasian, upholding a 1790 law. Then, in 1924, an immigration act passed by Congress effectively ended all Japanese immigration to the United States.

Where there was a will, there was a way to get around the racist laws, Dr. Chong points out. “Originally, the way the Japanese community tried to bypass it to buy land, they would leave it to the children who were born here.

“And then when they were succeeding in that, they started working with progressive members of the white society and would buy things under their name. And they were successful [with that as well].”

Dr. Chong observes that each Nihonmachi was unique, but there were comparable features, “You always have to have restaurants, sukiyaki and chop suey places, whether it’s produce, fish, Japanese products and hotels that could be for boarding or visitors. This was typical all across the Japantowns in California.

“In terms of society, the Buddhist church was a powerful force in keeping a cohesive community.” The large Buddhist church in Fresno’s Japantown became a center for community activities, education and sports.

Although known as Chinatown in Fresno, Japanese and other ethnic groups lived and worked side-by-side. “In Fresno, they were pretty much integrated,” notes Dr. Chong. “It’s not only Japanese or Chinese businesses, but you see Armenian and Mexican businesses; it’s all layered together.”

Until May 1942, Fresno’s Chinatown and Nihonmachi area was a thriving place, the Lost Kinjo project research shows. Dr. Chong writes that Chinese workers for the Southern Pacific railroad settled west of the tracks in 1873, and the first Japanese pioneers arrived in 1880 to farm Muscat grapes, replacing the Chinese workers after the exclusion law took effect.

Eventually, as the ethnic enclave grew so did the variety of shops and services. A look at the map of Fresno in the Japantown Atlas reveals the amazing diversity of small stores selling tofu and sushi, and hardware for carpenters, gambling joints, photo studios, laundries and bathhouses.

The center of Japanese life was on Kern and G streets and along Chinatown Alley within Fresno’s Chinatown. By 1940, Fresno’s Nihonmachi flourished with eight hotels, three boarding houses, 19 restaurants, 27 markets, five barbers, three bathhouses, three beauty shops, two theaters, three churches, six sewing schools and 120 other businesses. Komoto’s Department Store was a prominent business among the one- or two-story brick structures.

At its peak, 797 Japanese Americans lived in the city. Of course, many others lived on farms in the region and other Japantowns in Fowler, Visalia and Bakersfield.

After the war, many Japanese Americans did not come back to Fresno’s Nihonmachi, but a few did. Today, one business from the prewar era survives—Kogetsu-do, which makes traditional Japanese sweets.

Lynn Ikeda is the third-generation owner of the shop started by her grandparents. “They came from Hiroshima in the early 1900s. In 1915, they started the business on Kern Street. Then in 1920, they moved to F Street and it’s been here ever since. September of this year will be 109 years.”

Ikeda learned the exacting art and craft of making confections as she grew up working at the shop with her father. “Japanese pastries are made with rice flour or cake flour, and some have beans, Japanese red beans. There’s some fruit with pie fillers, which is cinnamon, apple, peach, apricot, blueberry, blackberry, raspberry and cherry.”

Their family was one of the lucky ones that could return when the war ended. “During the war, my grandparents and my parents were in relocation camps,” says Ikeda. “And when they came back, they had rented the store and their home. So, they were able to get it back when they came back to Fresno.”

Central Fish is also from this wayback era. It has achieved iconic status in Fresno as customers come from all over the city for the professionally curated fresh fish, Japanese food staples or to grab lunch.

Morgan Doizaki, part of the original family, is the manager. He celebrates all local cultures but says there should be some recognition of the Nihonmachi. “I still consider this Japantown. And not for ethnicity’s sake, but for historical reasons.

“It should be Japantown and not to take anything away from Chinatown because Chinatown is what we always decided to call this. But Kern Street should be something that has Japantown Street to signify the Japanese significance.”

Chinatown still suffers from the lingering resonance of racism and neglect by local economic and political powers. The blighted and abandoned buildings, once proud, cry out for attention and tender loving care.

There are people who do care about Chinatown and who have been working toward a better deal and a better day. The Fresno Chinatown Foundation is involved in several endeavors to improve this unique and essential part of the city. It will take money and commitment by City officials to make that happen.

To help achieve such goals, Chinatown business owners are on the steering committee of the Transformative Climate Change project. That is a $70 million fund intended to rejuvenate neighborhoods around the proposed high-speed rail station.

Even as it stands today, Chinatown and the echo of Japantown, with such a vibrant history and current mix of restaurants and shops, is a pretty cool place with a lot of soul.

There’s a lot more to Chinatown than most have been led to believe. Fresno Chinatown was a unique and diverse enclave of various immigrant groups that turned it into a major economic stimulus for Central California. The Chinese Exclusion Act was institutionalized and became an intricate part of the culture. While many of us have confronted these fears, too many of us allowed it to guide our community’s societal decisions. Unfortunately, we’ve lost our very history and essence as a community.