By Ellie Bluestein

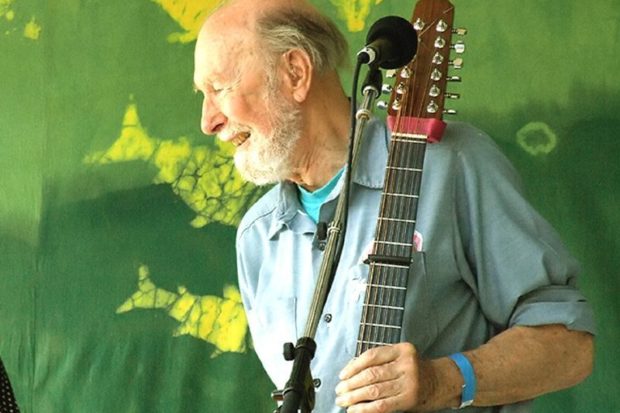

(Editor’s note: Pete Seeger was an American folk singer and activist who died on Jan. 27. Other media have presented wonderful reflections of his life and those can be easily found on the Internet. The Community Alliance is honored to present this article by Ellie Bluestein, whose family knew him well.)

Gene Bluestein and I met at a “progressive,” “left-wing” Jewish camp in upstate New York in the 1940s; Paul Robeson, Woody Guthrie and Pete Seeger came to sing there. There was suddenly a rush on five-string banjos with extended neck (just like Pete’s). He put out a couple of mimeographed sheets on “How to Play the Five-String Banjo.” Gene was hooked in a flash, and in no time was playing.

There was a tremendous surge of popularity in folk music: concerts, clubs, recordings, TV and the immediate leap to fame of the Weavers, which really brought folk music to prominence, although it was a slicker, more commercialized presentation than what Pete was used to.

But by 1950, an incredibly pernicious anticommunist scare swept Congress, the media and every aspect of American life. Investigative committees of Congress, of unions, of educational institutions, forced people to sign loyalty oaths and testify before Congress. Jobs and futures were at stake. Many people capitulated and had to give names of others. Some just left their jobs and sought anonymity and jobs elsewhere. Some pled the Fifth Amendment and refused to testify and went to jail.

Pete refused to answer questions on the grounds that he had committed no acts of disloyalty and Congress had no right to question his beliefs. He was tried and convicted and eventually the case was thrown out. But the Weavers disbanded; for 10 years, Pete could not appear on public media, and gigs were cancelled.

But young people who grew up singing with Pete were now teachers, parents, performers and were not willing to let it go. They set up house concerts, gatherings, bought the many recordings that Pete continued to make, and he never stopped singing.

We had just arrived in Minnesota for graduate school. Pete was traveling around the country trying to pick up gigs. He later credited these folks with having kept him going and putting food on the table.

Gene booked him for a house concert, which was great, lots of students as well as old timers, union folks. We were living in a basement with just cardboard walls, a bedroom and a tiny kitchen with a little table and three chairs. Pete sat in one of them, strumming the banjo and telling us that much as he loved the Weavers and the opportunity to bring folk music to a larger audience it wasn’t really his kind of performing—a set program, tight arrangements, no reaching out to and interacting with the folks or making up verses—not the living spontaneous music making that was his style.

We were in Minnesota for 10 years. The next time Pete came through we were living above ground so he was able to stay with us. He arrived with a serious sore throat and cold and could barely make a sound, but I set him up in our son Joel’s room with a vaporizer, and by evening he was able to make sounds and sing with us all.

Gene had completed his M.A. in English and was working on a Ph.D. in folklore and performing folk music all over Minnesota and even on tour. His first book, Voice of the Folk, leaned heavily on the work of John and Alan Lomax, who were Pete’s first mentors when he left Harvard and decided to learn from the folk. Gene was also much influenced by Charles Seeger, Pete’s father, who was a preeminent ethno musicologist.

Gene’s second book, Poplore, debunked the traditional folklorists who insisted that authentic folklore and folk music had to come from people no longer living, about incidents and subjects long past. For this, he was severely attacked by well-known academic folklore experts and received the following message from Pete inscribed on his book, Where Have All the Flowers Gone: A Singer’s Stories, Songs, Seeds, Robberies: “for Gene, with many thanks for writing your book, Poplore, keep on, Pete.”

On one of our trips East to see the grandparents, we took our kids to visit the camp where we had met. It was not far from Pete and Toshi’s home, so we dropped in on them and were welcomed like family as were the other millions of people who came to sing and hang out and help build the house made out of native rocks and trees hewn by Pete from the surrounding woods. Just one large room with a table where people could sit around and be together. And a beautiful view of the Hudson River.

Pete generously shared his wealth of knowledge and experience and creativity and was modest about his accomplishments. But he was totally scrupulous about giving credit to others for their work. Our daughter Frayda was home getting ready for her wedding when Pete called to ask if he might cite her rendition of “Bread and Roses” in his upcoming book, Carrying It On. Of course, Frayda was delighted that he liked it and gave it high praise in his book along with the family LP, Travelin’ Blues, on which it appeared.

After Gene died, our son Evo made a CD of Gene’s stuff that was left over and had never been put out, along with notes, and sent a copy to Pete. Pete replied: “Spent a fine hour and more listening to Gene and family and friends, reading the booklet. I hope it gets heard around the world, giving hope for the human race.”

*****

Ellie Bluestein has devoted much of her adult life to seeking peace and justice on a local, national and international level. Contact her at ellieb28@sbcglobal.net.