Californians United for a Responsible Budget (CURB), the Transformative In-Prison Workgroup (TPW) and many more community-based organizations and coalitions are shining a light on taxpayer funds that are invested in imprisoning bodies. These organizations are important for many reasons, but here we focus on their contributions to problematizing the uses of taxpayer dollars for harming bodies.

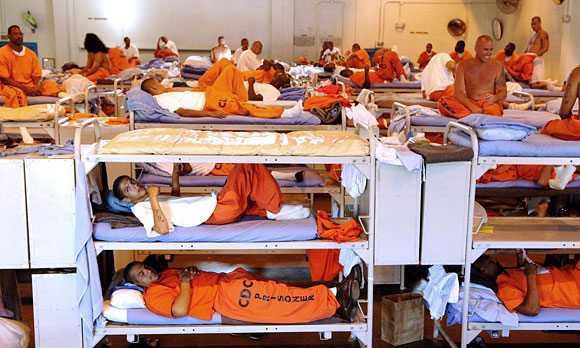

The California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR) maintains an annual budget of $14 billion for incarcerating a daily average of 103,000 people. The top uses of these funds go to prison healthcare ($3.7 billion), paying counties to keep incarcerated people local ($255 million), Covid prevention and safety practices ($240 million), facility improvements ($132 million) and substance abuse services ($126 million).

Ultimately, the budget is geared toward fulfilling the wider White supremacy directives of maintaining population control and oppression by disproportionately incarcerating BIPOC and poor people. The very history of prison use immediately following the Civil War was officially and overtly about the imprisonment of Black Americans as a secondary means of enslavement and chattel labor.

First the Black Codes and then Jim Crow laws ensured that generations of Black Americans were incarcerated for non-crimes, providing a powerful means of enacting U.S. White supremacy. U.S. prison use has maintained these purposes even as prison use jumped again with high rates of incarceration via racialized laws and their implementation in the War on Drugs. The CDCR simply fulfills the instructions of the racist intentionality of incarceration.

Some of the organizations that are challenging the uses of California taxpayer funds deliver programming inside of prisons, and still other organizations call for prison abolition. No matter the programming or the call for prison closures, the organizations draw attention to business-as-usual practices that earmark billions for imprisoning bodies as if these are “natural” and “inevitable” practices in terms of both state money management and population management.

For example, CURB focuses its organizing efforts on the reduction of “the number of incarcerated people in California, reduc[tion of] the number of prison and jails in our state, and shift[ing] wasteful spending away from incarceration and toward health community investments.” Its constant tracking of spending, organizing for powerful alternatives and redirecting funds into communities is well known across legal system reformers.

The TPW invests its coalition’s attention in “offering trauma-informed healing programs in California and New York prisons” with an advocacy and programming agenda. It spends a significant amount of time drawing attention to state budgets and the need for moving carceral funds into research-informed in-prison programming.

The 1% Campaign is one example of the TPW’s advocacy efforts, working with the California legislature to focus 1% of the CDCR budget on in-prison programming.

Furthermore, Initiate Justice (IJ) undertakes robust policy and organizing strategies to “end incarceration by activating the power of the people it directly impacts.” It engages the California legislature to write laws and policies that benefit people behind bars and change political trends, and comprise a team of members inside and outside of prisons.

Prison abolitionism is the strongest money-saving approach. More important, however, prison abolitionism has historically set its goal on deconstructing the racist agenda of the U.S. legal system and its uses of prisons for society-wide control of BIPOC and poor populations. Money savings is not the major aim of abolitionism; it is simply an aftereffect.

While White supremacist frameworks ensure racism and classism remain robust within all institutions, abolitionism is frequently framed as the looniest and most left-field idea. We argue that this misframing is really about deflecting attention away from public awareness of the White supremacy priority of the legal system and its prisons.

Abolitionism is a threat to business-as-usual because it requires the end of White supremacy.

The control and oppression of BIPOC communities is the top priority no matter the public relations efforts of institutions. White supremacy in other Western countries has unfolded according to the cultural features of those spaces. We can see the variations in White supremacy in the ways that money is spent, or not, on imprisoning bodies.

In some Western spaces, White supremacy control and oppression of BIPOC communities seem to occur outside the use of incarceration. This is a helpful insight for consideration in the U.S. context. Without anti-racist and decolonizing practices, control and oppression of BIPOC communities simply reshapes itself, shapeshifting because White supremacy is still the ultimate priority.

In Western cross-cultural examples, no one deserves an award for a lesser fixation on imprisoning bodies; White supremacy is likely enacted in a kaleidoscope of other ways even when it doesn’t look like California’s investment in entrapping BIPOC and poor communities generationally within the legal system.

CURB, the TPW, IJ and many more community-based organizations are important illuminators of the financial agenda backing the White supremacist methods of controlling BIPOC and poor bodies. They are also powerful examples of creative solution-building within a White supremacy society.

They problematize the uses of taxpayer dollars by indicating the minimal amount needed to engage in rehabilitative programming inside or outside of prisons and create revealing contrasts to denormalizing the management and punishment of our loved ones.

To learn more about prison abolitionism, check out the podcast Abolition Is for Everybody.