By Emily Brandt

Over the years, I have often wanted to peek behind the scenes to see the printing and producing of books or the field to table journey of food, but it was only in 2016 that I developed an interest in understanding the process of voting from the poll to announcements by the media of results. It’s a long process that doesn’t really end with the poll’s “100% precincts reporting” and the running tabulation that pops up on the bottom of our television screens during a long evening of watching county results roll in.

In fact, the media makes the process seem quick and clean. Most of us were aware before this election that primaries and caucuses operate quite differently than the November presidential elections. When I discussed my own experience regarding pledged delegates with a colleague who teaches history, however, I found that like he—like most of us—did not know anything about the procedures beyond the concept that the delegate and local parties carry out “the will of voters.” He was completely unaware of the complex steps one must take to become a delegate. Part of the confusion comes from the fact that the structure for Republicans and for Democrats are different and that each state operates differently. Those of us who have lived in other states and had to re-educate ourselves on the traffic laws find ourselves relearning voting rights laws, as well.

I was not alone in wanting to understand the processing of ballots after horrific memories of chaos in Florida and Ohio over the last several years. More recently Arizona and New York polling stations ran out of ballots, had very long lines, with poll workers who were missing in action. Records seemed to be mysteriously changed and or purged leading to widespread fear that our votes would not be counted. This primary election several of us regularly showed up to our local stations to observe the count, to learn about it, and to ask questions.

Without equivocation, I can say that I am very reassured by what I witnessed going on at the Kern Street County Office of Elections. As an observer, I was welcomed to ask questions of managers, not the staff engaged with the ballots, and able to watch from a distance of a few feet. Fresno County Registrar of Voters, Brandi Orth, made herself available to lead short tours and she was very generous with her time answering my questions. The procedure, I believe, is transparent and thorough. I could even hear conversations between managers and staff and read two computer screens.

My first day was on June 14th at the E. Hamilton Elections’ Warehouse. My tour was short since I was wearing sandals–a safety issue in the warehouse where massive stacks of ballots sit on top of each other in boxes. This is where ballots are counted with the optical scanner. It is the final step in the process so there wasn’t much going on there yet.

My first day was on June 14th at the E. Hamilton Elections’ Warehouse. My tour was short since I was wearing sandals–a safety issue in the warehouse where massive stacks of ballots sit on top of each other in boxes. This is where ballots are counted with the optical scanner. It is the final step in the process so there wasn’t much going on there yet.

The Kern Street headquarters is where the staff who process the ballots are trained. When I arrived there for the first time on June 15th, I was able to observe the staff being trained and got copies of their materials which explained how to process the Vote By Mail (VBM) ballots. There are four basic scenarios that can result in a ballot not being counted. They have to do with signature and address verification. Staff have access to websites that show the history of signatures and that list addresses for any given name online. This is the first year for Fresno County to be a part of the Vote California Statewide system that allows our county to access records of other counties.

Staff had just learned how to do this in the training. I could sense the timidity with which some new staff approached the process with the weight of responsibility to follow the protocol for verifying the authenticity of the voter information heavy on their shoulders. I was quite surprised to learn that even when a ballot is turned in to the wrong precinct, all the votes cast for candidates who are running for office in that precinct are counted; the only votes that are not counted are those marked for local candidates who are not running in that precinct. That often means that the ballot needs to be hand marked or duped (duplicated) so it can be fed into the optical scanner. This is a fairly common occurrence which takes a significant amount of time.

VBM voters also can vote at the polls, but they must surrender their VBM ballot to do this; if they don’t have them, they are usually given a provisional ballot.

The process was slow as staff found their rhythm and learned the ropes. The ratio of manager to staff was about 4 to 10 when I observed over several days. Supervisors review every ballot that passes through the system before it goes out in boxes to be counted at the E. Hamilton Street facility. If there is an error, the supervisor returns with the problem ballot/s and explains the solution. Staff go into the page online and make corrections. The total number of workers on Kern Street worked in two large rooms and was around 34 people. As the days passed, it became clear that staff were more confident, but were still cautious, and comfortable with calling over managers to help answer questions whenever they hit something they weren’t sure how to handle.

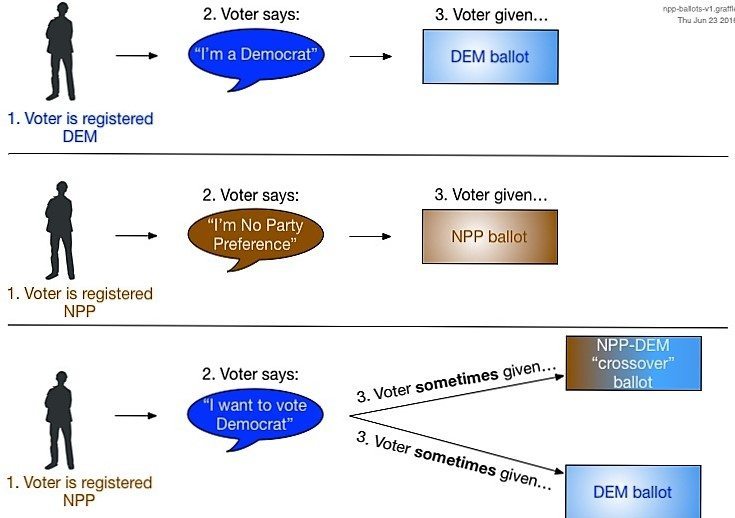

The VBM ballots are always the first to be processed. These are tricky because VBM voters who are registered as No Party Preference or NPP receive a postcard in the mail before May 9th. NPP voters were previously called Undeclared Voters. Since California has the Modified Closed Primary System, the added step for NPP registered VBM voters is to make certain they realize that they must request a Democratic ballot if they want to vote Democratic or American Independent (not Independent) or Libertarian. All other parties were barred from voting NPP because the parties notified the Secretary of State that they had chosen not to allow NPP voters to request their presidential ballots. The graphic below illustrates the resulting problem.

In Los Angeles County, this problem was brought before the County Registrar of Voters who decided that both the Democratic crossover ballot and the Democratic ballot would be counted for NPP voters because the main thrust of these decisions is guided by election law which tries always to preserve the voters’ intent.

After processing the VBM ballots, they begin processing the over 16,000 provisional ballots. Provisional ballots are given to registered voters who have not re-registered after moving to a new location within the same county. They are eligible to go to the polls where they would be on the roster if they had re-registered with their new address. Provisional ballots are put in pink envelopes with a form on the outside that needs to be filled in by the voter. Staff examine the envelopes and cross-check information before opening the ballots. There are seven steps to verify if the ballot will be counted. If any information is missing or if the voter missed certain deadlines, the envelope will not be opened and the vote not counted. The final step to observe before sealing and certifying the results is called the 1% manual tally of random precincts. Fresno County is just about ready to finish this now.

All ballots and voting records are stored for 22 months before being destroyed. There are still around 605,000 ballots left to count in California. Local election officials in Fresno county follow the law scrupulously. The only aspect I still find confusing is the 1% manual tally of randomly selected precincts done to verify that voting machines were tabulating correctly. The election’s code on that is not written very clearly, and the law is interpreted differently in each county. I believe most problems with voting occur at the party level. Parties have close ties to corporate media, make decisions that affect voter records, and create confusion in the process of voting by lobbying the California State Board of Elections. I encourage others to get involved by observing the count and learning about the process. Fresno County is still counting so our results are not final as the mainstream media would have us believe!

*****

Emily Brandt is an English teacher who teaches at a Fresno Unified high school. In her teaching, she steers clear of party politics, but points students to narratives as voices of social history.