By Hannah Brandt

This month marks one year since the UC Santa Barbara (UCSB) murders. That killing spree by a disturbed individual, Elliot, was an anomaly, though not as much as it should be. Although Americans like to believe our society exhibits enlightened views about race and women, ultimately we do not. We like to think that in beautiful places like Santa Barbara ugly things like sexual assault do not happen but they do. A lot. The reality is #YesALLWomen have been sexually assaulted.

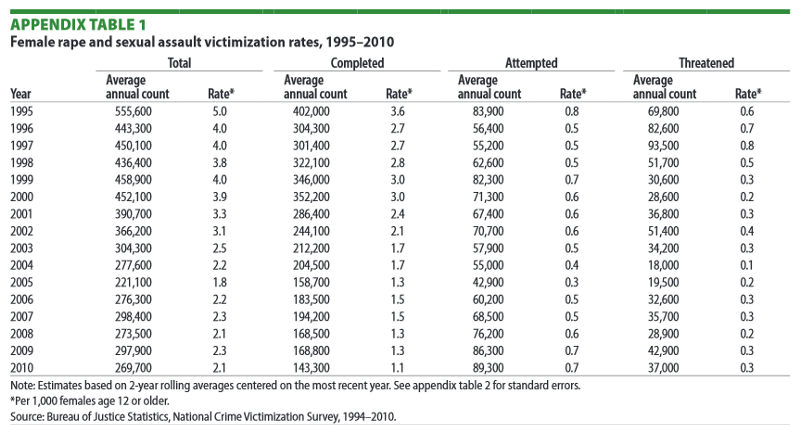

According to the Department of Justice, “In the United States, about 270,000 women were victims of rape and sexual assault in 2010.” Furthermore, a rape reported every 6.2 minutes in the U.S. and one in five American women will be raped in her lifetime. For girls and women of color, one in three will be sexually assaulted. For Native American women on reservations, 88% are attacked by non-native men who know they cannot be prosecuted on tribal land. Most women who are murdered in this country, like those that are raped, are killed by someone close to them such as a partner, ex-partner or acquaintance. Still, women are blamed.

Women are taught the “art of not”: not to wear anything provocative, not to go out alone at night, not to drink too much, not to have sex unless you’re in love or married. We are taught that you’re a prude if you dress buttoned up, no fun if you don’t get drunk and frigid if you don’t give it up when a guy wants you. In his deadly violence Elliott was an outlier, but in his feelings of entitlement to a woman’s body, he is an in-lier. How many women have been called sluts, whores or dykes for not responding pleasantly to vulgar pickup lines, catcalls or other forms of sexual harassment claimed by the perpetrators to be innocent overtures of affection? In doing so at this particular college, I have firsthand knowledge that he was very much an inlier.

I attended UCSB in the late 1990s, lived in its dorms and college enclave Isla Vista, and worked on campus. I loved to go to the beach at dusk and watch the waves roll by as I wrote in my notebook. I learned quickly, however, that as a woman a trip alone at night was as dangerous as a walk in my neighborhood in Fresno that struggled with gangs. A girl was gang-raped in a shed behind my apartment complex.

I was pathological about locking doors because a girl was raped in a nearby dorm by a male student who upon finding her door unlocked, sauntered in and attacked her while she was sleeping. That same year, a male coworker followed me home several times. No one I spoke to about him was gravely concerned. At first, he just did little weird things like staring at me in ways that put off everyone. “He’s awkward with girls.” “He just doesn’t know how to tell you he likes you.” Then he started to say weird things to me. “I want you to bear all my children,” he blurted out one day. I was visibly uncomfortable around him, yet had little choice but to work with him almost every day.

I would turn around to see him following me around the building like the towed vehicle hitched to my trailer, watching me like prey. His voice prompted a knot in my stomach that grew bigger every day. One day he threw a heavy plastic plate at my head after I ignored him. He missed, but not by much. He began to follow me home. As soon as I could, I ran inside and locked the door. This was before I or any of my friends had cell phones. My parents were worried when I called them and wanted me to report him because he was making me live in fear. Yet since many of my friends reacted as though I was overreacting, I questioned my fears, too. I wondered if maybe he was just socially awkward and harmless.

Eventually, I reported it to my bosses. They had witnessed the plate-throwing incident and I had already complained about him following me around work. “Just make sure you’re not the last one in the building.” “That guy? Don’t worry, you could ‘take him’ if he tried to get physical.” Even if you put aside the false assumption that only a big guy can inflict harm (Elliott was not a large guy), I was about 120 lbs. with arms like twigs. I wasn’t likely to be able to “take” anyone who wanted to hurt me. Naïve me, I didn’t realize going to university meant I should be prepared to throw punches.

No doubt, it’s chilling to see this scale of violence against women who rejected the advances of an angry misogynist on the same campus and same streets where I was stalked. Elliott’s racist jealousy toward a Black man for gaining a White woman’s affection is also familiar. That stoked the fire of rage in my stalker’s eyes. It makes me angry to know many feared the Black man I cared for, not my stalker. I felt safer when the man I loved was there. Of course, he could not always be around. I could not rely on his protection, nor should I have had to. I was one of the 500,000 women stalked every year in the United States who have reason to fear violence because of the women killed by their abusers, 75% were stalked beforehand.

Disappointed by my management’s response, I felt patronized, undervalued and unprotected. They were incompetent about sexual harassment. Based on recent examples from Columbia University to the University of Virginia, this continues to be the norm. UCSB is not an exception in its misogynistic culture. It is a cog in the machine that teaches boys to view their worth based on how many girls they “score.” The same machine that churns out rape jokes as predictably as pats of butter appear with bread at a restaurant table.

As a student manager, I often had to be the last one to leave the building and could only avoid that if someone agreed to wait for me to finish my work after they had finished theirs. Anyone who didn’t know about the stalking certainly had no compunction to do so. If I wanted them to stay, I had to tell them about my fears and hope they would not let their belief that I could “take” him align with their desire to go home. A few times I had my roommate pick me up in her car if she happened to be available to do so. Even that involved walking through the dark back dock and bushes that could easily have hidden any guy.

I’d like to say he stopped stalking me and I was able to live out the rest of college without any fear. He graduated a year before me and moved a couple of hours away. I thought I’d never have to see him again. If he ever did try to visit after he was no longer a student, management surely would not let him given his history toward me. However, the next year, while at work, he’d suddenly creep up next to me. Fearing that if I spurned or ignored him, he’d be provoked to do, well…something like Elliott, I suffered through him following me around yet again a few times. I realized later that I should have reported him to those in higher positions at the university or to the police, but I would not have been surprised if their reaction was similar. Unfortunately, abuse and negligence are devastatingly common when college women do report their harassers and attackers.

Locally reported cases of rape on campus and in Isla Vista made me constantly aware that universities were not safe places. Sexual harassment is not limited to large universities; it happens at small colleges, religious institutions, and high schools, too. At a Catholic school in the Bay Area, boys took pictures up their female teachers’ skirts and shared them online with vulgar comments. I experienced similar things as a high school teacher. It is not only socially awkward “weirdos” like Elliott and the guy who stalked me that are guilty. “Only about 4% of violence in the U.S. is committed by people with a diagnosable mental illness,” according to Dr. Renee Binder of UC San Francisco. That means that the majority of men who commit acts of violence against women are “normal, healthy guys.”

How far would things have had to go before I’d have been taken seriously? He didn’t grope me, but other men have at parties, on the street or on public transit. He didn’t say vulgar, abusive things to me either, but plenty of other guys have. It is so normalized in our society, we usually expect it and feel helpless to stop it. Most women I know have been groped and stalked. We giggle uncomfortably about it together, trying to reassure ourselves that if it is not unusual, it cannot really be that scary. Deep down we know it is.

Many encounters at parties were equally appalling. I was very careful. Like my driving, I practiced defensive living while female. I resisted the overwhelming peer pressure to go through college in a drunken stupor. I don’t know how many times I heard, “you should drink more, you’d be more fun.” When a college guy calls a college girl “fun” in that context he means “easy.” For some, it means if you were drunk and passed out, I could force myself on you and you wouldn’t struggle. How many times has that happened and the girl has silently suffered because she had been warned by concerned elders not to get drunk? How many girls thus become convinced that it is their fault? That they are just sluts and they deserved it? How many sexual assaults are filmed and shared on smartphones, so girls are humiliated in front of the whole world?

My experience is far from unique and many American women suffer through much worse. People might say I was lucky I wasn’t viciously violated by violence: yes. I refuse to call living in fear lucky, however. In that way, no woman on the planet is lucky. We are all unlucky. Instead of recognizing the failings of our system to respect women, Americans tend to point fingers elsewhere, railing against parts of the world where the media focuses the majority of its attention regarding sexual assault cases, primarily against White women traveling in majority non-White countries. It is often put down to being a problem with the culture in these faraway countries. It is a problem with the culture, but it is a global culture.

White men commit sexual assault just as much as men of color, rich men as much as poor. As The Hunting Ground, the excellent new documentary about the epidemic of sexual assault on college campuses so vividly displays, women need be just as afraid of the trust fund, frat boy slipping roofies into her drink as the homeless man masturbating outside the 7-11. She is just as likely to be sexually assaulted while waiting for the New York subway or caught in the throng of drunken (primarily affluent, White) revelers on Del Playa in Isla Vista as she is to be attacked at a political rally in Tahrir Square in Cairo.

It is dangerous to continue to bury our rape and sexual harassment statistics behind the stories of rapes and sexual harassment in other countries. Harassment and violence against women is a problem worldwide and will not end until this country confronts our role in it. #ALLMenCan help our culture cease to be hostile toward women by not thinking, speaking or behaving in misogynistic ways, making other men accountable when they do, and teaching the next generation how to truly treat women with respect.

*****

Hannah Brandt is a freelance journalist who has previously published in the Community Alliance and the Fresno Bee. Contact her on Twitter @HannahBP2, where she runs @FresnoAlliance.