“We can never fully right the wrongs of the past. But we can take a clear stand for justice and recognize that serious injustices were done to Japanese Americans during World War II.”

—President George H.W. Bush, in a letter of apology to former internees, 1990

Manzanar National Historic Site is many things: museum, history archive, archeology site, learning center and living community resource. A lot goes on there.

Visitors can learn firsthand about the experiences of Japanese Americans who lived in this concentration camp. Or learn the history of the Owens Valley Paiute and the ranchers and farmers at Manzanar in the time before World War II.

Historic Site workers take care of the site’s historic orchards and excavate and preserve camp gardens. Every year, hundreds of schoolchildren and nearly 100,000 visitors come through. Volunteers participate in landscaping projects, archival projects and serving visitors.

Before it was a national historic site, Manzanar was already a legend. As the nation’s first War Relocation Center to open in the wake of Executive Order 9066, it was a city with a peak population of 10,046 Japanese Americans.

A one-square-mile city with a barbed wire border and watchtowers, it lay in the shadow of Mount Whitney amid the stark beauty of the Owens Valley at the junction of the high desert and high Sierra. It was hot in summer, cold in winter and windy much of the time.

People who left there after it closed on Nov. 21, 1945, carried little but their memories and some of the artifacts they had created. Those recollections have been transformed over time into dozens of books featuring memoirs, history, novels, murder mysteries, even graphic novels.

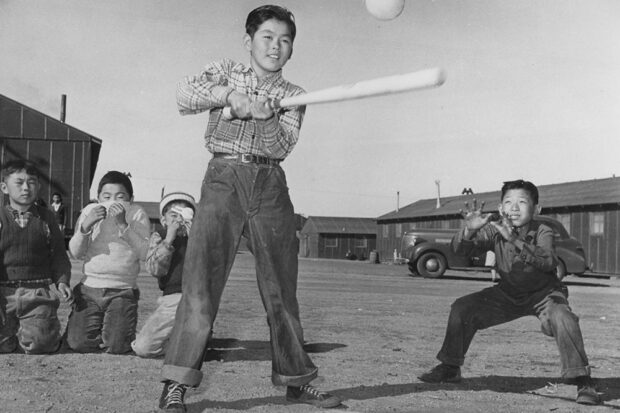

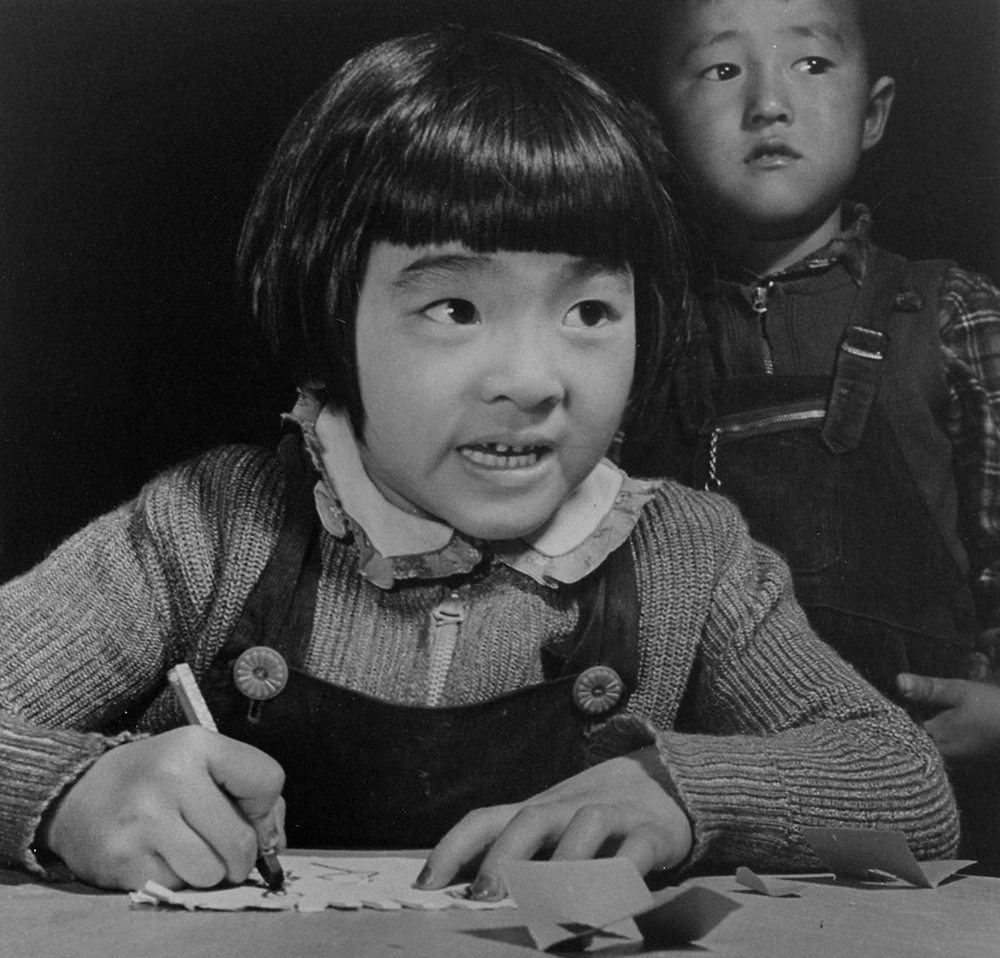

Famous photographers such as Ansel Adams and Dorothea Lange documented life at Manzanar during the war years and published what they saw. Commercial photographer Toyo Miyatake smuggled in a makeshift camera disguised as a lunchbox when he was interned and took photos of what existence was like on the inside.

In establishing the Manzanar National Historic Site, the U.S. government solidified the legend. It came about as a consequence of social justice movements in the late 1960s and a remarkable individual.

Sue Kunitomi Embrey came to Manzanar in May 1942 as a 19-year-old and worked as a teacher’s aide. She later became a reporter and managing editor for the Manzanar Free Press.

Years later, she helped organize the Manzanar Pilgrimage and in December 1969 a group of 150 people made the first trip to the remains of the concentration camp. She led the pilgrimage for 37 years and accomplished an even loftier goal of official recognition for Manzanar as an important touchstone in American history.

Sarah Bone, a Manzanar interpretive National Park Ranger, shares the history and special features of this unique place. Noting the pilgrimage is now in its 55th year, she says those events were vital to creating the national historic designation.

“There are a lot of different layers,” says Bone, “but I’d say the most important acknowledgement we need to give is to Sue Kunitomi Embry and the Manzanar Committee. The committee has been coming since 1969, and they started coming to acknowledge the history here, but also in the context of what was happening in 1969.”

Energized by the social justice consciousness of the era, the Manzanar Committee wanted to turn the War Relocation Center into a platform for public education. Embrey worked to preserve Manzanar to raise awareness.

“If more people knew that places like Manzanar existed, more people would be aware and maybe would speak out,” says Bone. “So, she [Embry] has an education background and an activism background, and she started first in the early 1970s with trying to get the state to acknowledge this as a historic landmark.”

In 1972, Manzanar was recognized as a California Historic Landmark and the state placed a landmark plaque on Highway 395, after a successful lobbying effort by the Manzanar Committee. Then, after pushing hard on the federal government, the national historic site was designated by Congress on March 3, 1992.

From the National Park Service (NPS) perspective, the site had advantages because the land was intact and belonged to the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power, making it easily obtainable. And the proximity to Los Angeles, just a few hours drive away, made it accessible to a large population. Ninety percent of Manzanar prisoners were from there.

The work of the Manzanar Committee and other Japanese Americans was just beginning. Developing the historic site became a labor of love over the decades as former internees, as well as other Japanese Americans, volunteered to create the national treasure one visits today.

Before there was a Manzanar, the landscape was home to the Owens Valley Paiute people exclusively. That changed in the 19th century with the coming of pioneer European Americans who took the land as their own for ranching and farming.

By the early 20th century, a Southern California agricultural developer named George Chaffey had built an irrigation system and established a small farming oasis with 480 acres of apple orchards, along with additional parcels of peaches, pears, plums and grapes. Soon, a few dozen families moved in and created the small community of Manzanar, the Spanish word for apple orchard.

By the mid-1930s, as rapidly growing Los Angeles drained an increasing amount of water from the Owens Valley through its aqueduct, farming declined and the people moved away.

In the aftermath of the war, the concentration camp was deconstructed except for one building. “We were very lucky that the building that became our visitor center was still here,” says Bone. “It’s an original building. It was built and completed in 1944.

“The people that built it were incarcerated here. And it was built as the auditorium for Manzanar high schools, so [it was] where they would have plays and dances, but also as the largest building in the community of Manzanar, things like funerals and other events would happen here.”

That remaining building was renovated by the park service to become the visitor center and museum that opened in 2004. Next, the NPS had to consider the options and decide on a plan for the site.

It settled on constructing a small demonstration block within the larger camp that included barracks where families had lived, a mess hall and large communal latrine. There were 36 such blocks in the original camp.

The aim, according to Bone, was to give visitors a small taste of what it must have been like to live there. “We built reconstructions of two barracks and a latrine there so that people could kind of see the conditions that people were living in.

“And they think about day-to-day life; these are human stories, and so us as humans visiting it are most likely to make those connections if we kind of think about it that way.”

Manzanar is an active archeology research field where people can volunteer to help. “Our cultural resources manager has established a pretty long-running community archeology program,” says Bone.

“And so he has weekends and weeks, spring break time or holidays, when people can come up and volunteer their time and give us a lot of help to uncover gardens and to reconstruct pieces of Manzanar in our landscape.

“They get to reconnect with this story or connect with this story for the first time in a way that the average visitor does not get to do.”

History is alive in Manzanar. Not just events writ large but also the stories of individual people that Bone says illuminate what really happened. “We have an oral history program here where we have over 700 interviews, and every single person is different.

“We might even interview siblings that literally went through the same thing, but they have very different ways of looking at it and feeling about it, and things that impacted them. So, there were over 10,000 people here at Manzanar at its peak, and that’s 10,000 different stories.”

Many visitors to Manzanar are, of course, Japanese Americans, including those who had been interned there and their families. It’s a special experience for the rangers, and it underscores the value of oral histories.

“I think that’s one reason these personal stories are so important,” says Bone. “It’s reminding the person that we’re interviewing or that we’re talking to, or that we’re learning from, how important their life is because if nothing else they were not made to feel important during the war.

“But it’s also reminding all of us that we’re all human beings and we all have ways that we will react to this and things that we will do that’s very different.”

Their goal, Bone emphasizes, is truthfulness, “We don’t need to filter it. We want the people here to be making those connections directly to people that were incarcerated.”

Manzanar is a place that should be seen to be fully appreciated, “I remind visitors that when they’re walking, they’re experiencing it in the same way that people incarcerated here were experiencing it,” said Bone.

“They were walking everywhere they were going, and you’re doing so in the weather, no matter what the weather is. So, it’s a very experiential experience here.

“And you can look down and see pieces and parts of Manzanar everywhere. You’ll see the foundations of some of the buildings. You’ll see the gardens, but you’ll also see nails and marbles and the ends of tin cans that people used to plug the knot holes so that the wind wouldn’t blow into their barrack building. And that’s everywhere, literally everywhere.”

For those who cannot make the trip to Manzanar, there is a Virtual Museum online that is designed to bring exhibits and archives to a wider public to explore. Through photos, prose and oral history, the Virtual Museum takes one on a journey around Manzanar and its history in a dynamic format.

You can learn about local history before the war, the racism and exclusion that sent people here and camp life including the rich archive of art and artifacts people made. There is a lot to learn and a lot to feed the soul.

An important part of being a ranger at Manzanar is to help people connect with family and history. Bone reports that many Japanese Americans and some Japanese nationals come, “some of them have connections to the incarceration. Some of them were incarcerated themselves.

“And as there was such diversity in the people incarcerated, there’s certainly diversity in the families of those that were incarcerated. Some will come many generations later with very little knowledge of what their family went through because it was not talked about openly; it was kind of too big of a scar to open with the family.

“And so we do our best to help, help make the connections back to those generations.”

Linking the past to the present day is another prominent goal at Manzanar, “A lot of the organizations like the Manzanar Committee that helped create Manzanar are looking at the things happening today and making those connections. When these exhibits were built and we opened our visitor center in 2004, we were making the connections to 9/11.”

Manzanar National Historic Site is more than a window into the past. Bone emphasizes why it is important in our time. “It’s such a human story, and we all connect to it from our own perspective. But from the bigger perspective, and I hope as a park ranger here that, it’s important today because it’s such a relevant topic.

“Yes, this happened 80 years ago, but racism and othering and things like that are a constant thing that we think about and learn about and deal with every day in our lives. We might be talking about different groups of people in different circumstances, but the pattern is very clear.

“And so, we have visitors that walk in the door and go into the exhibits and come out and tell us stories about their own personal lives that are brought up by their experience here at Manzanar.”

Reflecting back on the original motivation of Sue Kunitomi Embrey to create Manzanar as an institution for advancing civil rights, Interpretive Ranger Bone looks to the future. “I still hope that we are taking the important lessons that human beings had to endure here. Taking from those experiences, we move on into the world and we are speaking up for ourselves and for our neighbors.

“We can learn from this very human experience what it might be like to be othered and to be incarcerated because of your race. So, it’s a relevant story that I hope we can all learn from whatever that may be for us as individuals.

“We may be drawn to different things because of who we are, but we remember Manzanar as a lesson for us as human beings.”