By Tom Frantz

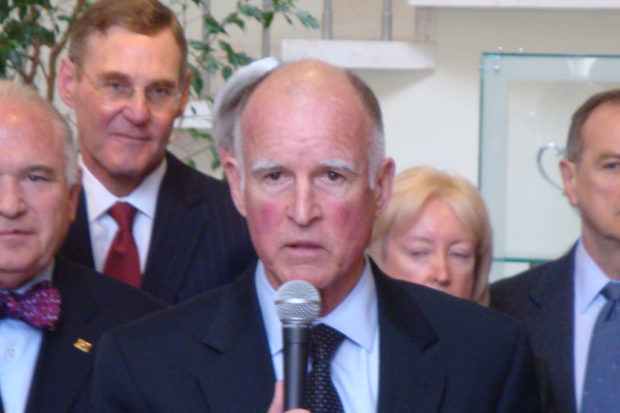

On June 3, 2015, an interesting lawsuit was filed by farmers in Kern County against Governor Jerry Brown, a few regulators and a couple of big oil companies. The lawsuit claims there was a conspiracy by these entities to pollute the groundwater used for drinking and irrigation of crops for the purpose of increasing their profits.

It all started a few years ago when a local farmer, named Mike Hopkins, noticed his young cherry trees were dying. He replanted a good part of his orchard and lost all of the new trees as well. Eventually, he tested the groundwater he was using for irrigation and found a high salt content, especially boron, which is not normally in well water in this area.

He was aware of nearby oil field activity and that wastewater, separated from crude oil, is routinely injected into the ground nearby. He was upset to learn that some of this salty wastewater had apparently migrated into the fresh groundwater he had been using for decades to water various crops in his field. He had assumed the oil companies were following all the rules and regulations regarding the injection of wastewater so that adjoining sources of groundwater were fully protected. He also assumed the government regulators in charge of this kind of practice were actively enforcing all of the appropriate rules.

Hopkins hired a lawyer and sued the nearby oil companies in September 2014 for trespass and damage because of the contamination of his groundwater. The oil companies claimed they were simply following the law and had done nothing illegal. The local judge in Kern County told the farmer that his lawsuit was inappropriate. He could not sue the oil companies but instead needed to sue the state agency responsible for permitting the injection of wastewater by the oil companies.

Hopkins was no doubt frustrated, so he and the lawyer discussed suing the California Division of Oil, Gas and Geothermal Resources (DOGGR), which approves these wastewater injection permits. An investigation was launched by the lawyer to determine the history of these permits.

The lawyer discovered that there were strict federal rules against injecting wastewater into clean sources of water used for drinking or irrigation of crops. The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) was already questioning the validity of some of these California-issued permits. She also discovered that these rules had not been enforced properly in California for many years. There had also been an increase in applications for this type of activity. It seems that with the increased injection of steam to get the remaining thick oil out of the ground there was a concurrent increase in wastewater production that needed to be disposed.

Upon further study, the lawyer was surprised to discover that in 2011, Governor Brown had fired the top regulator of this activity at the DOGGR who he had appointed just a few years earlier. It was well-known in political and oil industry circles that this regulator had been trying to follow the rules for protecting groundwater and that had caused a delay in permitting. Therefore, a new regulator was put in place and the permits, plus the wastewater, again flowed freely.

The new regulator even e-mailed the head of permitting in Kern County and spoke to her of his satisfaction that they were now all on the same page. Meanwhile, the groundwater was slowly being contaminated under Hopkins’ cherry orchard.

A few months ago, it was announced by the federal EPA that many oil companies were injecting wastewater into good groundwater illegally. The EPA ordered that this practice stop. Many people around the state wondered at the incompetence of the DOGGR for having permitted this activity, which endangered such a valuable resource as the groundwater that people were using for drinking, bathing and irrigation of food crops.

It became obvious to this lawyer that the entire situation had not happened by accident. It was clear that the big oil companies, and some of the smaller, independent oil companies, had used their money and political influence to convince Governor Brown that they desperately needed many new permits to inject wastewater and they did not need anyone looking over their shoulders. The alternative was that they might have to slow the production of oil and their profits might shrink. They also threatened that jobs and tax dollars might be lost.

It turns out that Governor Brown’s political connections to big oil likely caused him to want to help the industry make larger profits. That is why he apparently fired his own chief regulator of the oil industry and appointed someone he could trust to not cause any more problems in holding up permits.

Hopkins’ lawyer thought about this sequence of events and saw clearly the planned conspiracy that allowed this to happen. She saw how this one farmer with a ruined cherry orchard and ruined groundwater was a victim of this conspiracy and how many farmers in the area were being threatened with the same disaster.

As a result, a lawsuit was filed against Governor Brown on behalf of Hopkins and unnamed other farmers. This lawsuit was filed under the RICO Act. RICO stands for Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations. The name comes from the past need to prosecute leaders of the mafia for conspiracy when they could not be found guilty of directly committing criminal acts. This is a special kind of lawsuit where a conspiracy by a group of people is alleged to have happened for the purpose of illegal gain.

Governor Brown is going to have to prove his innocence, which may be difficult. One of the new appointees Brown made to smooth over these permit issues has just resigned. Like the similar FIFA lawsuit affecting world soccer, the dominoes are beginning to fall.

*****

Longtime clean air advocate Tom Frantz is a retired math teacher and Kern County almond farmer. A founding member of the Central Valley Air Quality Coalition, he serves on the CVAQ steering committee and as president of the Association of Irritated Residents. For more information, visit www.calcleanair.org.