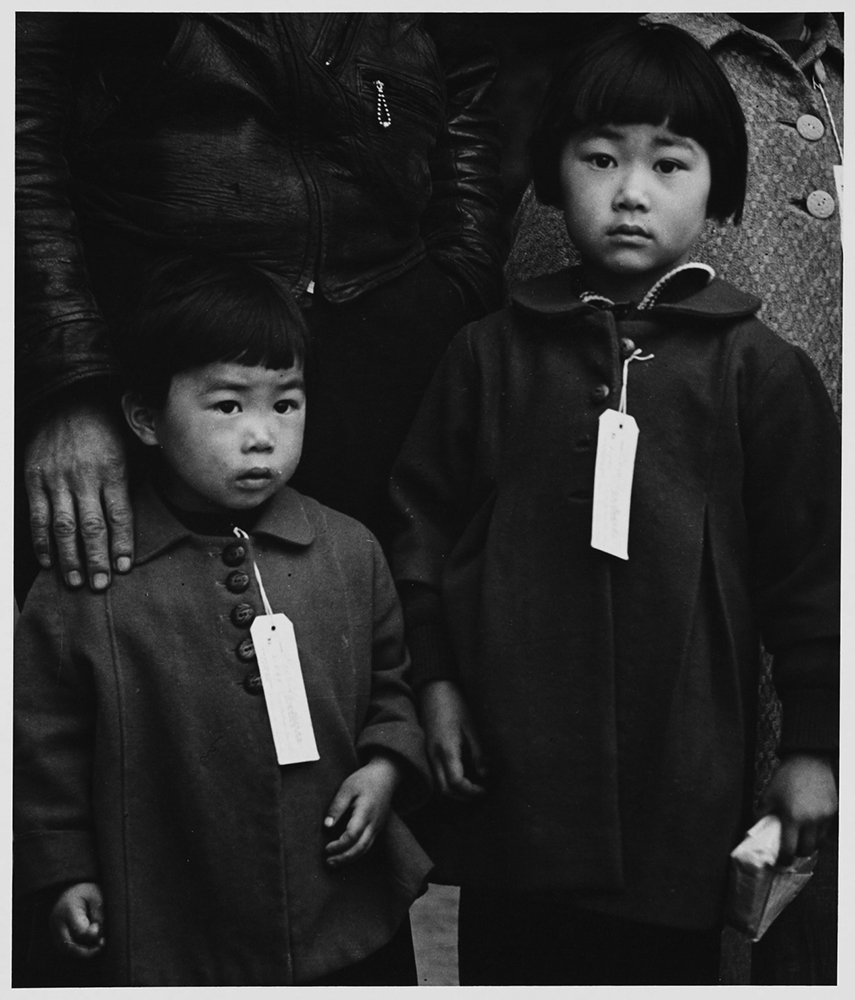

In 1942, the infamous Executive Order 9066, signed by then President Franklin D. Roosevelt, ordered all Japanese immigrants and Japanese Americans living on the West Coast to be interned in concentration camps because, according to the authorities of that time, they represented a danger of espionage or sabotage in favor of Japan during World War II. The executive order was signed after the attack of Pearl Harbor, in Hawaii, by Japan.

There remains no proof of any espionage or sabotage carried out by citizens of Japanese origin.

More than 120,000 people were sent to camps around the country. The majority of them were nisei, those born in the United States. The rest were sansei, the children of nisei, and issei, immigrants born in Japan with residency in the United States.

Although the United States took similar action against Germans and Italians, they represented a small group of people incarcerated compared to the Japanese, which led to the conclusion that racism played an important part in who would get incarcerated. At the time, most Americans approved this measure without any evidence of disloyalty by the Japanese.

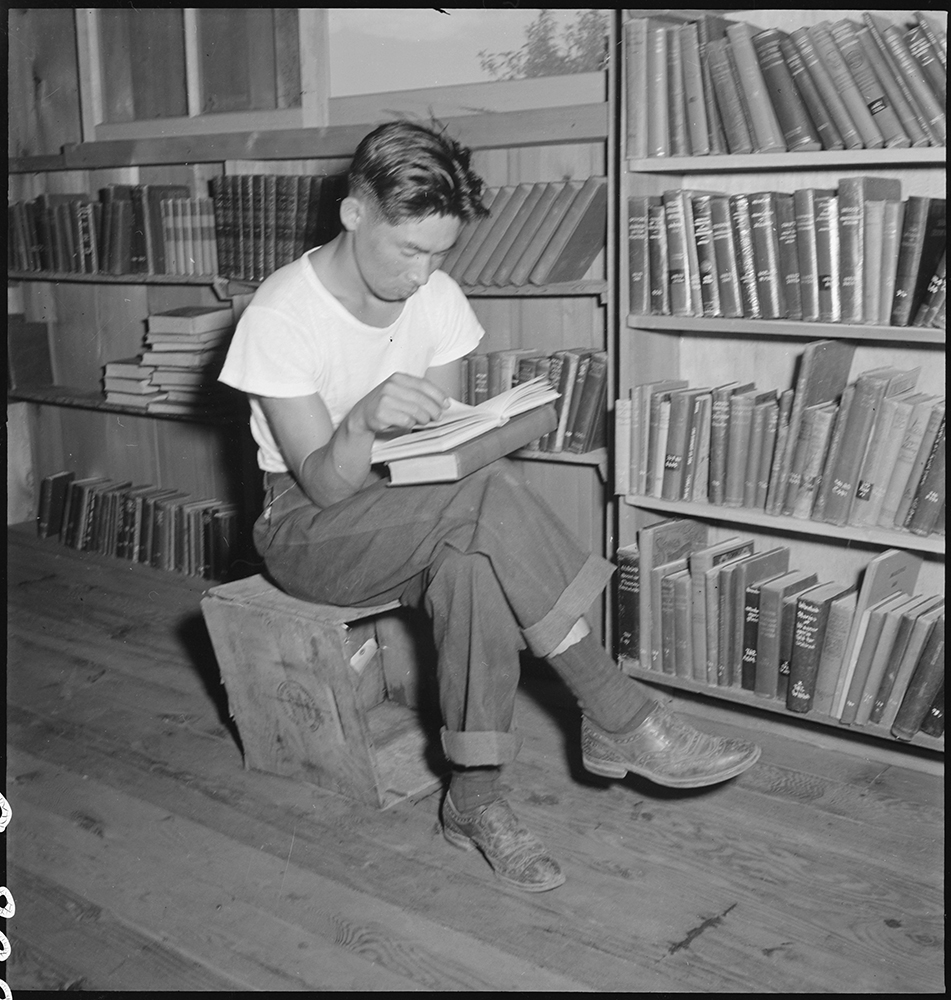

When WWII was over, the incarcerated Japanese were liberated. Many of them lost their property during the incarceration, which represents an ominous act of state violence and abuse.

The Japanese fought over time for the U.S. government to recognize the abuse and for their dignity. It finally paid off when in 1983, a report, “Personal Justice Denied,” by the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians (CWRIC,) found “little evidence of Japanese disloyalty at the time and concluded that the incarceration had been the product of racism.”

In 1988, the U.S. government apologized for the Japanese incarceration and paid $20,000 in compensation to each former detainee.

Photos courtesy of the Central Photographic File of the War Relocation Authority and the Dorothea Lange Digital Archive

Boy, talk about grace under disgraceful conditions! Foisted on an entire culture by…US!