The Interfaith Scholar Weekend takes place yearly in Fresno. This year marks the return to an in-person format for the first time since the beginning of the pandemic. It was held the weekend of March 10–12.

At the morning event on Saturday, held at Temple Beth Israel, Rabbi Rick Winer said prayers in Hebrew during a Torah interpretation. The Torah is a sacred Jewish scroll, and a different portion is interpreted each week of the year.

Following Rabbi Winer, representatives of several other faiths gave short talks and prayed aloud.

Afterward, Hajj Reza Nehumanesh, the executive director of the Islamic Cultural Center of Fresno, came up to the Rabbi, excited, and said, “Hey bro! Didn’t we have, like, six languages?”

They counted off the six: Hebrew, Arabic, the Lakota language, Armenian, Punjabi and English. A little later, there was a Buddhist meditation that was done partly in Japanese. This is the essence of the Interfaith movement—each language a testimony to its culture and its people.

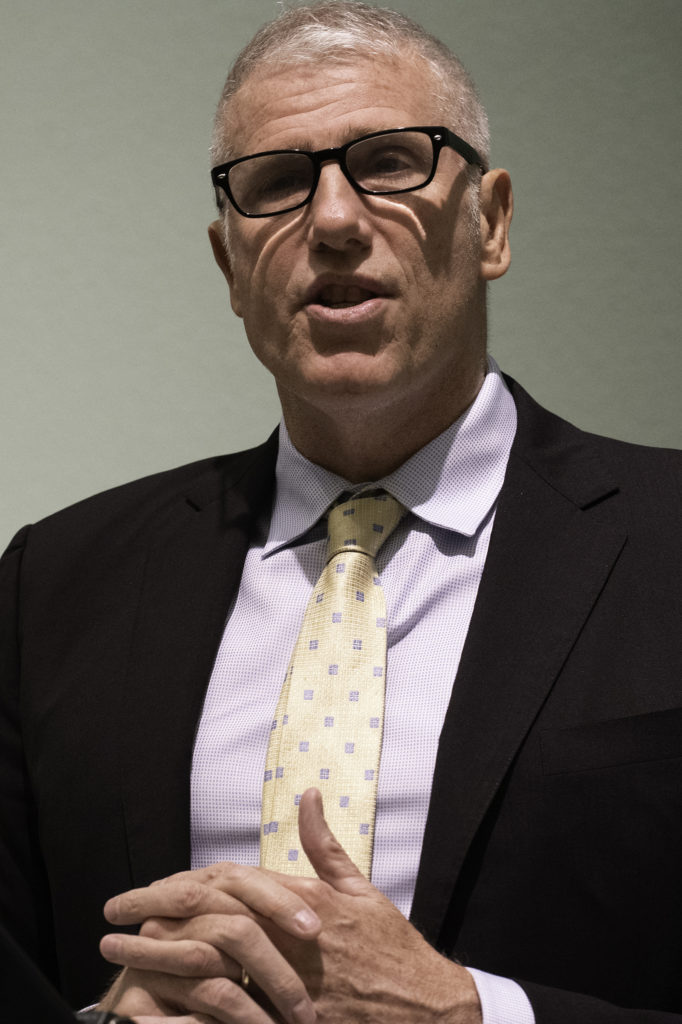

Rev. Paul Raushenbush came from New York to headline the event. He spoke at the Saint Paul Catholic Newman Center on Friday, at Temple Beth Israel on Saturday and at the Unitarian Universalist Church on Sunday.

Raushenbush is president and CEO of the Interfaith Alliance. He is an imposing figure, at almost six feet five inches. He is a Baptist minister and for eight years was associate dean of religious life and the chapel at Princeton University. He is openly gay, married and with children. He has experience with web publications and religious journalism, including a stint as executive editor of global spirituality and religion with the Huffington Post.

In his keynote address at the Newman Center, Raushenbush said that “nearly one in five Americans assert that not only is the United States a white Christian nation, but also that they are willing to fight to preserve it.

“We saw this when the white Christian nationalists marched through Charlottesville with torches saying, ‘Jews will not replace us!’ Or when President Trump used tear gas and violence on the protestors in Lafayette Square in order to hold up a Bible as a prop at St. John’s Church.

“And of course, most notably on January 6, 2021, in the deadly attack in our nation’s capital by insurrectionists holding crosses and waving Jesus banners as they attempted to thwart the will of the people in the election and subvert our democracy.”

Raushenbush, whose great-grandfather was Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis, offered the legal principle for opposing these Christian nationalists: “Your freedom to swing your fist ends where my nose begins.”

He also found reason for optimism in America’s religious-political climate: “We’re going to stand up to Christian nationalism by naming it, by saying [that] it’s not what we want our country to be.

“And we’re also going to win by casting a much more beautiful vision for this country, for our communities, for our city, for our nation that invites everyone to participate with equal dignity for the people of faith and no faith to live their life freely together.

“We will celebrate an inclusive understanding of religious freedom and demand that our religious and moral and ethical commitments—around racial equity, marriage equality, freedom of women and public schools—deserve equal treatment to those who claim the mantle of religion, but mean it to benefit the very few.”

Several local figures gave responses to the keynote speech. Among them was Sukaina Hussein of the Council of American-Islamic Relations. She said that the Quran has several references to religious freedom.

She said, “One of the verses I want to highlight is chapter two, verse 256. God tells us, because the Quran is the word of God, he literally says [she read the citation in Arabic]. That means there is no compulsion in religion.

“And so God is literally telling us you cannot force someone to believe something. You cannot force someone to have a change in their heart. You cannot force faith upon someone.

“We talk about ‘there is no compulsion in religion’—you hear that from Muslims a lot. We’re talking about what God told us. That might not be what you see in some Muslim governments, and it might not be what you see from some oppressive rulers, but it is what our faith teaches and what God teaches.”

Raushenbush took the mic again and gave Hussein glowing praise: “Every time I hear all those stories, those stories from the prophet Muhammad, from the tradition, I’m like, yeah, oh my God, thank God for those stories. They give me language; they give me strength as a Christian. You’re basically creating a corridor, creating a broad, a beautiful entrance and saying, ‘Hey, come learn.’”

The next afternoon, Raushenbush’s lecture was titled “Response to Online Hate and Offline Violence.”

“Hate speech is content intended to vilify, humiliate or incite hatred against a person or a group on the basis of their identity,” he said. “Online harassment is a weaponization of content against members of marginalized communities, including religious communities. And importantly, no matter where it occurs, hate speech puts the safety of our friends and our neighbors at risk on and offline.

“If you think about the Tree of Life [synagogue] murderer, he was on Twitch telling a community that he was going to go do this. And then he went and did it because he was in a like-minded group. [The Internet] creates a dangerous political climate.”

Sadly, he added, “Silicon Valley and other tech areas are going through economic turmoil, a lot of layoffs, [and] the first people who are laid off are the teams that monitor hate and misinformation online.”

In the big picture, it’s safe to say that Raushenbush is amazed by the power of the Internet.

“There’s a parable that goes, two fishes are swimming along, and they pass an older fish,” he says. “And the older fish says, ‘How’s the water?’ And the two younger fish kind of swim on and they say, ‘What the hell is water?’ The Internet is water. And we have no sense of what we’re diving into when we dive in.

“The Internet is the most important invention that humanity has ever made. And we’re living through the beginnings of it. We’re just at the beginning of it. You might say, ‘Oh, well, the printing press.’ The printing press? Forget it. How many apps do you want for a Bible?”

At one point, he held up his smartphone and said, “This is the largest theological library that’s ever existed in the world.”

The final part of Saturday’s event was a workshop on advocacy. The Interfaith Alliance lobbies legislators for religious and democratic rights.

“For the most part,” Raushenbush said, “we have not been invited into Silicon Valley.” Given the enormity of the changes big tech has made, and the impact they have on our society, perhaps that is a dialogue the progressive religious could undertake. In the generally positive and forward-looking atmosphere of the Interfaith Scholar Weekend, that even seems possible.

What To Do about Hate on the Internet

Source: Interfaith Alliance

Call out, but don’t engage. Instead of engaging with the harasser, engage with the impacted person. Avoid sharing hateful content, even when demonstrating your opposition.

Report the hateful content to the platform. Although they might not be perfect, most social media platforms have mechanisms by which you can report hateful content. Report hate when you see it to stop it from spreading. Incidents of hate speech should be taken seriously.

Block the source. Unfollowing or blocking the speaker can help limit the reach of their hateful content.

Show solidarity with the targeted person or community. Lifting up the voices of impacted communities can help drown out hateful content. Show your support for the persons targeted by reaching out and showing your support.