The UN Development Programme (UNDP) warns that the progress made in human development in recent decades could be slowed or even reversed by climate change when new threats emerge to food security and water, agricultural productivity and access, nutrition and public health.

Sea level rise, droughts, heat waves, floods and variations in rainfall are some of the effects of climate change that could cause an increase in the number of people experiencing food insecurity. Many climatic phenomena could become more intense, including river floods, flash floods, urban floods, sewer floods, glacial lake outbursts and coastal floods.

Furthermore, one of the world’s leading scholars on the topic, American environmental economist Robert Mendelsohn, expressed his concerns, saying that because agriculture is essential to human survival, the effects of global warming on productive croplands are likely to threaten population welfare and national economies.

Until recently, most analyses of how climate change would affect the food and agriculture industries concentrated primarily on how it would affect food production and the world’s food supply, giving other links in the food chain less weight. Food costs have increased dramatically in recent years, severely hurting vulnerable people.

Although definitions of food security help drive its goals and guide policy decisions, it’s equally important to consider the processes that result in the intended ends. All four dimensions of food security—availability, accessibility, food utilization and stability of food systems—are impacted by climate change.

Based on the reviewed literature, climate change will severely impact food security. The effects will range from local to national and global when any of these four dimensions of food security are affected.

Its effects will be long term due to shifting precipitation and temperature patterns and short term due to more frequent and intense extreme weather events. Nevertheless, although food availability has been the main topic of most research, the other three dimensions of food security have not received enough consideration.

Food Availability

The physical amounts of food produced, stored, processed, distributed and traded determine food availability. The adequacy evaluation is conducted by contrasting the availability of a food item with its estimated consumption demand. This method balances domestic markets, considering the significance of both domestic production and international commerce in guaranteeing a nation’s food supply.

These components are analyzed in the Food and Agriculture Organization’s national food balance sheets, among others. Food balance sheets provide crucial information on a country’s food system in three categories: domestic food supply, food utilization and per capita total food supply values.

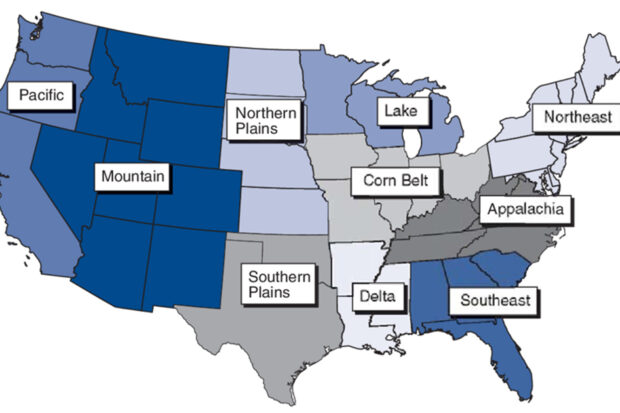

According to the 2022 statistics by the U.S. Department of Agriculture and Economic Research Service, in the United States, there are more than two million farms and agricultural production occupies more than half the country’s land. The statistics indicate that the number of farms has been slowly declining since the 1930s, though the average farm size has remained unchanged since the early 1970s.

Food Accessibility

Food accessibility is a function of one’s capacity to get entitlements, which are the social, legal, political and economic resources necessary to access food. Accessible and healthful food is essential for survival. Also, food has strong ties to social interactions, community and family.

The absence of safe and reliable food access can also negatively impact social networks and community support systems. The issues surrounding food access are complicated and have many overlapping causes. These include corporate dominance of agriculture and food, unemployment and poverty, unequal access to healthcare, and unpredictable weather and climate.

Furthermore, food accessibility ensures that everyone has physical, social and economic access to enough wholesome food that satisfies their dietary demands and preferences while meeting their needs for an active and healthy life.

Food consumption might be hampered by health problems and loss of access to drinking water, and it is expected that food access and utilization will be indirectly impacted by collateral impacts on household and individual incomes. The data demonstrates that significant funding is required for mitigation and adaptation measures in order to create a “climate-smart food system” that is more resilient to the effects of climate change on food security.

Food Utilization

The term food utilization describes how food is used and how a person gets necessary nutrients from the food they eat. The changing climate is expected to bring changes in eating patterns and new problems for food safety, all of which could impact nutritional status in different ways.

There are significant adverse implications of climate change on food consumption. The decreased availability of wild foods (a collection of fresh fruits, fresh mushrooms, and fresh plants and vegetables) could impact food consumption and restrictions on small-scale horticulture production because of water constraints or labor shortages brought on by climate change. In addition, new pest and disease patterns, a recent phenomenon exacerbated by the changing environment, will impact human and plant health.

Food System Stability

In addition to food and agricultural production, other food system activities such as processing, distribution, acquisition, preparation and consumption are crucial for ensuring food security. One of the most significant issues in adapting to climate change is ensuring food security in the setting of rising disaster risks. Rising food prices have increased the potential for adopting better land management techniques. However, several adaptation options in agriculture face a dilemma.

Adaptation to Climate Change

The UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) took effect on March 21, 1994. The 198 nations that have ratified the agreement are Parties to the Convention.

The ultimate goal of the UNFCCC is to stop “dangerous” human meddling with the climate system. Annual UN climate change conferences, often known as COPs, are the world’s sole global climate change decision-making platform, with nearly all nations participating.

In this case, little East African countries like Djibouti, home to just over a million people, or major powers like the United States, China and Russia have the same influence over decision-making processes.

What is adaptation? The UNFCCC defines adaptation as “the processes through which societies make themselves better able to cope with an uncertain future.” Taking the necessary steps to mitigate its negative consequences (or capitalize on its good ones) through the required modifications and adjustments is part of adapting to climate change.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) defines adaptation as “adjustment in natural or human systems in response to actual or expected climatic stimuli or their effects, which exploits beneficial opportunities or moderates harm.” Additional adaptation components include developing resilience to change and learning to manage new hazards.

An IPCC study from April 2007 cautioned that the world was not moving fast enough to stop the severe effects of excessive greenhouse gas emissions on the environment and economy.

The Global Environment Facility, the Adaptation Fund, the Least Developed Countries Fund, the Special Climate Change Fund and other bilateral, regional and multilateral channels have all offered funding proposals for adaptation measures; however, these proposals must be significantly increased in order to meet the challenge of climate change adaptation.

The goal of international negotiations such as the Conference of the Parties (COP) capacity-building framework is to provide financing bodies with a framework for carrying out their capacity-building initiatives related to climate change.

COP decisions can have global authority. Furthermore, decisions can only be reached by consensus. Every year, COP is held; COP 28 is the 28th Conference of the Parties to the UNFCCC that took place in Dubai, United Arab Emirates, from Nov. 30 to Dec. 12, 2023.

Parties to the UNFCCC send representatives to participate in the negotiations. Observer organizations also send delegates, and industry representatives and lobbyists attend. Other specialists and stakeholders are present, including business executives, youth, climate scientists, Indigenous peoples and media.

The COP consists of blue and green zones. The UNFCCC is in charge of overseeing the blue zone. Delegates from UNFCCC-accredited organizations can attend speaker and panel events and country negotiations.

The host nation is in charge of the green zone, which gives unaffiliated groups a platform to advance the conversation on climate change. More than 69,000 people attended COP28. Negotiations at COP28 hope that Parties will deliver an ambitious agreement that sets the world on a more sustainable future.

In short, the purpose of the COPs is to reach a global consensus on solutions to the climate catastrophe, like keeping the increase in global temperature to 1.5 degrees Celsius or 2.7 degrees Fahrenheit, assisting societies that are most vulnerable to the consequences of climate change and reaching net-zero emissions by 2050.

Additional adaptation strategies involve land-use changes that take advantage of modified agro-climate conditions. Agriculture extends beyond farms. It includes industries such as food service and food manufacturing. It also relies heavily on land, water and other natural resources that climate affects.

The pace, intensity and degree of adaptation of farmers and ranchers will determine how climate change affects agriculture. Crop rotation and integrated pest management are only two of the several climate change adaptation strategies now used in American agriculture.

Regarding agricultural production and water, climate adaptation might include the following:

- Water-wise irrigation systems

- Risk management

- Initiatives to help small farmers and other vulnerable groups protect and promote agricultural production, including improving agricultural extension services to increase yields

- The establishment of independent climate information exchange networks between farmers and among communities, cities and counties across the region

- Using crop species and types with stronger resilience to shocks, drought and heat stress

- Modifying irrigation techniques, including amount, timing or technology (e.g., the drip irrigation system)

- The adoption of water-efficient technologies to harvest water, conserve soil moisture and reduce siltation and saltwater intrusion

- Enhanced water management to stop erosion, nutrient leaching and waterlogging

- The integration of the crop, livestock, forestry and fishery sectors at farm and catchment levels

- Planning for inclusive, accountable and transparent adaptation, with the active involvement of people all around the region

Conclusion

Building capacity to adapt to and address the problem of climate change requires immediate investment at all levels. The domains of climate science and institutional frameworks need capacity building for human resource experts. Furthermore, climate change poses a significant national threat that necessitates swift, cooperative, equitable and responsibly shared action.

To effectively cooperate on climate change concerns, political commitments from both the federal and state levels are required, as well as the involvement of major stakeholders from the climate change community where they are not currently active.