By Paul Thomas Jackson

Homeless advocacy may be divided into two categories: Intervention and prevention. Governmental and nonprofit organizations and church groups with a culinary flair, as well as the gourmet-pleasing Food Not Bombs, intervene in the lives of homeless people, affording temporary relief in their plight.

As preventers of homelessness, such organizations may also be subsidized. That is to say, they may use public funds to prevent a person or family who’s facing the imminent prospect of homelessness from actually falling into it. In the case of a family, scholars agree the best practice is to increase affordable housing; and to provide appropriate income and work supports for low-income families and for survivors of domestic violence so that they have the tools they need to preserve and regain housing, good health and child development. “At-risk” families should be preserved as families since the family unit is generally regarded as the basis of human society.

Advocacy organizations like the generically-named Western Regional Advocacy Project are also examples of preventers. As discussed in Mike Rhodes’s Dispatches from the War Zone, they analyze public policy, showing how it actually fosters and maintains homelessness. By raising readers’ awareness of the policy in question, readers might use whatever tools of democracy are at our disposal to reform, if not reverse it. The scandal of such a high rate of homelessness in the world’s richest society almost cannot be overstated!

Locally, Fresno Homeless Advocates does intervention work, prevailing upon our elected officials to do right by homeless people. Since Pres. Obama announced “Opening Doors” in 2010, that initiative has not focused on families, but two other subgroups: homeless veterans and the chronically homeless. Most of the local organizations that provide services to the homeless and needy do both: They intervene in the lives of people who normally welcome their help; and within their means, they prevent applicants from becoming homeless. Scholars agree that permanent supportive housing is among the best practices to bring homelessness to a functional end in those two subgroups. In addition, veterans are well served by re-housing and expanding services relating to discharge and employment.

In this article, ‘solutions’ to homelessness includes both interventions and preventions. By listing a wide variety of solutions here, the writer does not imply that one of them is correct or superior. Nor, unless imminently feasible and comprehensive in scope, is one solution necessarily superior to others not mentioned.

One crucial consideration is whether a solution has only a brief impact on someone’s life. A program that would leave him or her unhoused at a later date does not prevent homelessness. To hold a discussion on these life-changing matters, a group would first need to reach the consensus that proposing or exploring such a short-term plan does not have that motive is behind it. And, any community conversation lacking that consensus is probably doomed to misunderstanding or serious confusion among the discussants.

Sleeping rough

Sleeping on the street, known in Europe as “sleeping rough,” is a good example of a purported solution that should not be mistaken as though it is meant to condone homelessness. It is merely a provisional solution when the only alternatives are a night of undisturbed sleep under an oleander and being rousted and cited for public trespassing during the wee hours. But, of course, homeless advocates seek to expand the availability alternatives. It’s a mere stop gap.

Three-day tent camp

An ordinance like Nevada City, California’s (contained in chapter 9.14 of its municipal code) is a stop gap for the very short term. That ordinance permits homeless people to pitch tents on public property for up to three days. Yet, the right to do so without police harassment normally comes as welcome relief to an unsheltered person.

Far from establishing such a right, Fresno City Council attempted to ban tent camps here in December of 2011. At that time, three dozen homeless advocates attended the city council meetings and many spoke out against the proposed passage of an anti-camping ordinance. Yet, this apparent success leaves unpermitted tents within Fresno City limits a legally questionable activity.

‘Right to Rest’

Sen. Carol Liu’s “Right to Rest Act,” if passed into law, permits an unsheltered person to rest or sleep in a public place as a necessary function of the person’s life. The principle at stake here—the human body’s need for sleep—underlies the Ninth Circuit’s reasoning in its 2006 decision in Jones v. the City of L.A., as well as the statement of interest that the Department of Justice made in 2015 in Bell v. Boise. The constitutional principle holds that a homeless person should not be punished for sleeping out of doors when there are not enough beds to meet the need of every homeless person. Argued successfully in triggering the Eighth Amendment, the principle has been applied to only those two lawsuits and without any chance of application in future suits. By legislative fiat, however, Liu’s bill secures a right on the same principle.

Shelter

Warming/cooling center

The opening of a cooling or warming center for some few days, perhaps weeks, is another stop gap. No statute or regulation requirement known to this writer requires the establishment or use of such a center. In Fresno, warming centers became widely available in 2008—after the $2.35 million settlement of the lawsuit brought on behalf of homeless people here— on extremely cold nights between 7 p.m. and 7 a.m.

Two British medical studies, cited in a previous Community Alliance article by this writer, conclude a distinct risk of hypothermia exists well above the temperature set by the City of Fresno’s warming-center policy: “When temperature predictions fall to 36 degrees F, Frank H. Ball Neighborhood Center gymnasium is opened” (www.fresno.gov/News/PressReleases/2008/WARMINGCENTER.htm). Since hypothermia has been shown in cases at 51 degrees F, which is 15 degrees warmer, the city’s warming center policy appears a failure.

Because no statute or regulation requires a warming center, there is no requirement that a city open one when the weather reaches a certain low temperature. Still, the city’s policy causes people to rely on its failed policy, so that they attempt to enter a center on a 37-degree night, only to be confronted by a city employee who turns them away and leaves them in a far worse condition for having made arrangements to store their winter gear at some distant location. No statute or regulation says the employee cannot. But, by the same token, the courthouse door is wide open to arguments the temperature under the City’s policy should be higher—if standing to sue can be established.

‘Safe and legal’ shelter (Five-or-more-day tent camp)

Organized camps, particularly tent camps such as proposed by the Advocates, will exist for five or more days; and realistically for at least one year. Upon approval by the County of Fresno public health officer of an application to operate such a camp, the operator (be it a person or organization) is subject to the concurrent jurisdiction of the California Department of Public Health and the Fire Marshal. (H. & Saf. Code, §§ 18897.2 and 18897.4. Re jurisdiction of organized camps, see, generally, id., § 18897.6; and Organized Camps. 45 Ops.Cal.Atty.Gen. 41.)

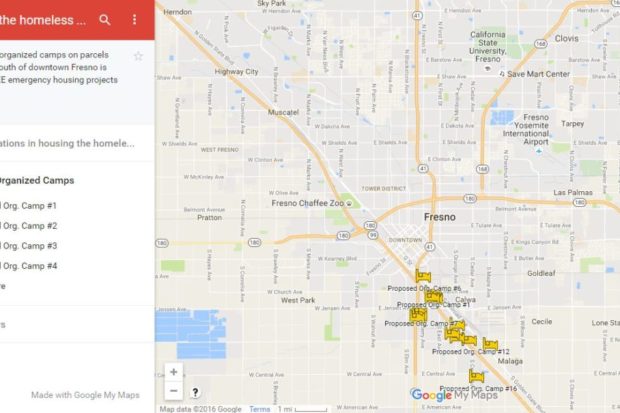

The officer may renew the application to operate for another year. It appears the only legal way to have a tent camp in California is with an organized-camp status. And while a tent cannot have a heating facility within its walls, a housing unit must have one. Organized-camp sites proposed by a committee of the Fresno Homeless Advocates are in the second layer of the map at www.google.com/maps/d/u/0/edit?hl=en_US&app=mp&mid=zZfSI1yVYV6A.kao29k1py0-g.

Before listing additional shelter and housing options, this writer gives a caveat: Since two federal initiatives were begun—Pres. Obama’s “Opening Doors” and the VA’s “25Cities”—local organizations whose programs have a residential component have streamlined their enrollment processes and consolidated their resources. Consequently, the availability of beds and program enrollment periods may have varied since the online map was devised.

Short-term transitional “housing” (shelter)

In short-term transitional housing programs, a person may enroll anywhere from one month to three months. Such programs in Clovis and Fresno are in the first layer of the Advocates’ online map at www.google.com/maps/d/u/0/edit?hl=en_US&app=mp&mid=zZfSI1yVYV6A.kHgd8KymbO1c.

Housing

Long-term transitional housing

Long-term transitional housing programs, in which a person may (generally speaking) enroll from three months up to two years. In these long-term programs, the person may participate in such services as case management, mental health and medical services, counseling and general issues groups, life and social skills groups, anger management, vocational and educational training, advocacy, and assistance obtaining benefits and identification information. Such programs appear in the second layer of the online map on the last-mentioned website.

Special needs housing

Special needs housing, such as is administered by the Fresno Regional Foundation (whose principal office is at the Figarden Financial Center). Such programs appear in the third layer of the online map; a glance impresses one with Fresno’s large number of these programs, which are primarily for developmentally disabled people.

Additionally, residential care facilities include family homes, group care facilities, including some transitional housing facilities for the 24-hour, non-medical care of people who need personal services, supervision, or assistance essential for their daily activities.

Subsidized housing

Subsidized housing, the largest program of which is Housing Choice Voucher, often still called “Section 8.” In Clovis and Fresno, subsidized housing appears in the second and third layers of the online map at www.google.com/maps/d/u/0/edit?hl=en_US&app=mp&mid=zZfSI1yVYV6A.kk2V6FroqX_w.

Independent housing

Independent housing may consist of a tenancy in an apartment or a house. Or it may be a second unit adjacent to a single-family home, usually occupied by an elderly individual needing the maintenance, repair, and/or added security provided by a formerly homeless person.

Since 2004, the city has permitted homeowners in “R-1” the right to add a second unit to their lots. The Fresno Development Code (at § 15-6702) defines such a unit as one “providing complete independent living facilities for one or more persons that is located on a lot with another primary, single-unit dwelling. A second unit may be within the same structure as the primary unit, in an attached structure, or in a separate structure on the same lot.”

Second units call for no government subsidy. On the contrary, a homeowner might derive a modest source of (rental) income from a formerly homeless person who might also agree to keep guard of the residence or to perform basic maintenance or gardening. As Mike Rhodes says, when the government has failed the homeless, we ourselves might be of help to them.

Permanent supportive housing

Permanent supportive housing, such as those sites in Clovis, Fowler, and Fresno appear in the first layer of that online map. Such housing is among the ‘best practices’ to functionally end homelessness for both veterans and the chronically homeless.

Commitment to residential institution

In clear cases of risk of serious danger to one’s self or others, a person may be committed to residential institutions such as psychiatric hospitals. Jails and prisons–though in abundance in the Central Valley, and though ‘permanent’ and ‘supportive’ of some lifelong inmates’ most basic needs–are not deemed a solution to homelessness, at least insofar as the Fresno Homeless Advocates are concerned.

Conclusion

The continuum of solutions and purported ‘solutions’ for homelessness depends on the brevity or longevity of a particular solution. This framework of information is a way to understand the relationship among the many possible solutions, including housing options (when available). It is a guide that might prove helpful to frame a discussion of addressing the homelessness crisis, a nodus that requires careful attention and consideration such as found on the pages of Dispatches from the War Zone.

There are conflicts inherent in the foregoing ten solutions. The pursuit of one solution is possibly, even likely in some instances, to be at cross-purposes with another. None is intended to condone homelessness, and no such implication should be drawn! The ‘solution’ to homelessness varies with the particular needs of the individual so that some conflict between possible housing options and solutions would seem inevitable.

If you use Facebook, the Fresno Homeless Advocates invite you to join our Facebook group.

*****

Paul Thomas Jackson is an L.A. native who first came to live in Fresno in 1996, transferring to Fresno State as a Public Administration major. A decade later, he prepared the claims that paved the way for the homeless lawsuit that settled for $2.35 million. He now administers the Fresno Homeless Advocates’ Facebook group of about 200 members.