By Patsy Mejia

Recently, I had the distinct privilege to participate in a pilot program initiated by the Mexican consulate aimed at reconnecting university students with parents or grandparents of Mexican nationals with their roots and providing a chance to give back to those communities through various volunteer opportunities. Nearly 150 students from California, Illinois, Texas and North Carolina traveled to México for five weeks over the summer to one of five states: Michoacán, Jalisco, Yucatán, Oaxaca and Hidalgo.

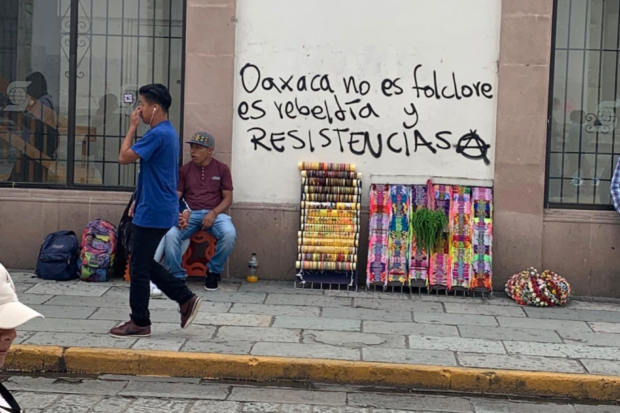

in Oaxaca, México.

I was selected to participate in the program in Oaxaca. There are eight regions in Oaxaca: Cañada, Costa, Istmo, Mixteca, Papaloapan, Sierra Norte, Sierra Sur and Valles Centrales. My family is from the Mixteca region.

We travel to my dad’s small town every few years whenever possible, but I never delved into the history of our culture until I left for university. I was placed in Oaxaca for five weeks.

The program provided us with an insight into the everyday lives of Oaxacans. We visited various artisans where we learned how they weaved baskets from carrizo, or reed, stitched traditional clothing and even created an artisanal soda called Zega-cola.

Growing up, I was always aware of the traditional artisan products that came from Oaxaca. My maternal grandparents were artisans and campesinos. At a young age, my grandfather taught me how to make tenates, or woven baskets from palm, and my grandmother taught me how to embroider colorful napkins for tortillas. They also tried to teach me how to speak their native tongue, Mixteco.

I appreciate that the program exposed us to a wider range of artisan products, but I had hoped that we would not experience this through the lens of a tourist. While visiting artisan Guillermo Mendoza in his pueblo of Santa Ana Zegache, where he makes baskets out of reed, I had hoped that we would also have the opportunity to learn how to weave, much like my grandparents had tried to teach me many years ago. Instead, I watched on as he sat down to weave and my peers immediately took out their phones to record.

At the time, I could not explain why I was so hurt, but now I understand that I did not like how the artisan was treated like a spectacle. We were, in essence, tourists in our parents’ countries, but there had to be a more respectful way to engage with these communities. I hope the program can work around this and provide a space for students to interact with artisans in a more meaningful way.

Our volunteer opportunities included providing support for the events during the time of the Guelaguetza—an annual display of indigenous traditions and customs from the eight regions of the state. We provided security for many events and support for others where we would set up and break down. These were great opportunities to enjoy the various events that surround the Guelaguetza.

We also were able to receive one Zapoteco lesson from children and give them an English lesson. In addition, I was part of a small team of students who gave English lessons to tour guides and hotel workers. It was during these classes where I realized that I might want to pursue education in the future in order to provide English classes to adults in my hometown. Although the English classes we provided were a few days in length, I hope they made some type of impact.

Overall, I thought that the program was a great first step in reconnecting children born in the United States to the land of their parents, especially because we are born with the privilege to travel freely between the two nations. I enjoyed visiting new places in Oaxaca but am cognizant of the fact that many Oaxacans themselves are not able to travel so freely between tourist spots because of a lack of economic opportunity.

I would also like the program to establish more interactive activities, especially when visiting artisans in their pueblos. More important, some sort of orientation as to the history of Oaxaca is of extreme importance. Oaxaca is one of the most revolutionary states in Mexico, from agriculture to education, workers, communities and entire towns unite to fight for social justice.

Understanding the state’s rich history in activism is a stepping stone into understanding the stories that influence us to this day. I am grateful to have spent a summer in my parents’ home state of Oaxaca. Although there were some aspects of the program that can be improved in the following year, I deeply appreciate all that I learned in the five weeks I spent in Oaxaca this summer.

*****

Patsy Mejía is a senior at UC Berkeley, where she studies political science. She enjoys the cool weather and the mostly left-leaning political concentration of the Bay Area, but Madera is where her heart is. Contact her at patsymejia@berkeley.edu.