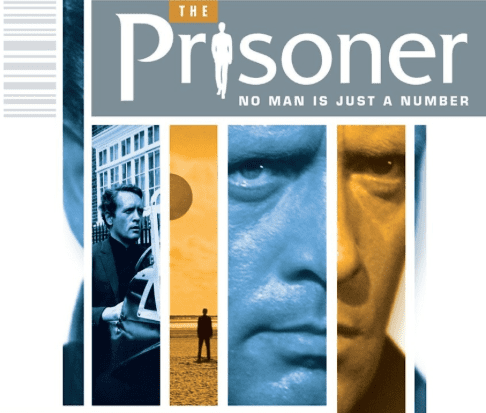

Back in the late 1960s, The Prisoner was my favorite TV show by far. It was a quirky spy-type series, and in it a British agent was whisked away to a clandestine site known only as The Village.

In one memorable episode, a new fad was taking all of the Villagers by storm. It was something called Speed Learn, and it promised to give participants vast amounts of knowledge in record time.

By the end of that show, though, the agent discovered that Speed Learn offered far less than it appeared to. In fact, its adherents weren’t actually learning much at all.

Something similar has been going on in the Fresno Unified School District (FUSD), although instead of Speed Learn it’s called Edgenuity.

What is Edgenuity, and how does it work?

Suppose you’re a high school student who’s failed an important class—or several classes, in fact. The clock is ticking, and you still need to rack up a given number of credits so that you can get your diploma.

Enter Edgenuity, a so-called credit recovery program. In some high schools you’ll be invited to come to an Edgenuity session. There, you’ll sit in front of a computer screen, read and answer questions, and ostensibly do enough work so that you can succeed where, otherwise, you would have failed.

Students are required to attend these sorts of sessions in person; they can’t just complete the tasks in the comfort of their own homes. An instructor is in the room monitoring student progress.

On the surface, it seems like a laudable program that leads to a happy conclusion for all concerned. But all that glitters is not education.

Start with the time it takes for someone to complete the assignments designed to make up a semester’s amount of work. Depending on a student’s speed, the workload might be finished within a few days—which means that several courses’ worth of credits can now be acquired within a few weeks.

Another issue: The content of the assignments isn’t aligned with the curriculum for the courses that the students failed. If someone fails a math class, say, he or she won’t necessarily be mastering the skills and knowledge that were covered in that specific course.

“It’s not about learning,” remarked one Edgenuity instructor. “It’s about credit recovery.”

The unsettling aspects of the program don’t stop there.

Google “Edgenuity” and “answers,” and you’ll come up with several sites that provide the answers for these assignments. As one teacher told me, this is becoming common knowledge among students. “The cheating is an open secret—think ‘three monkeys’ imagery.”

To call these sessions “classes” is a stretch.

“It’s not teaching,” one Edgenuity teacher said. “I’m just at the laptop monitoring the system.”

He went on: “It’s like air traffic control.” By which he meant that interacting with the students in the room was neither required nor, apparently, encouraged.

Teachers are actively recruited to fill extra pay positions for Edgenuity sections.

Note that Edgenuity is a nationally available vendor. Scenarios such as these aren’t just happening in Fresno, but in other districts as well.

In one recent case, a senior accumulated more than 40 absences and more than 60 tardies in one class during a single semester. His grade was dismal: The points he’d accumulated added up to less than 10% of the total points possible. Thanks to the intercession of credit recovery, though, he stood at close to 50% completion for that course after less than three hours’ worth of credit recovery assignments.

Another issue: the timeline sometimes used when assigning students to these sessions. It’s not uncommon for students to be placed in these groups before a term has come to an end—giving them zero motivation to make up work, do extra credit or prepare for a final exam. All of that has become irrelevant for them during the final weeks of the semester.

“What we are increasingly worried about is that as the word spreads that it is ‘this easy,’ many non-college-track students will find it tempting to just ignore their semester’s worth of learning and opt for this,” mused one veteran teacher.

The implementation of programs such as Edgenuity raises some troubling questions about the nature of public education as it’s sometimes structured these days. What, exactly, is a high school diploma worth if it can be earned this way? What do students involved in such a program learn about consequences or about personal responsibility?

To be sure, graduation rates will soar if programs like Edgenuity are implemented consistently and aggressively, and the district’s reputation will shine. But at what cost is this happening? What’s the effect on a community when a significant number of students are denied the education that they were promised and given a diploma that they haven’t legitimately earned?

What happens to the status of teachers—and of teaching itself—when programs like this one take root and become normalized? The answer seems to be clear enough: It marginalizes the role of teachers and the perceived value of actual learning, and it undermines the acquisition of such traits as perseverance and concentration that true learning depends on.

Not too many years ago, the FUSD announced that it was preparing college and career-ready graduates. How does that worthy goal square with the use of this sort of program?

In the fall term, Edgenuity will be a regular class in some sites; some students have already been assigned to it. Instead of taking a traditional course—an elective such as art, for example—they’ll be completing Edgenuity tasks day after day, week after week.

One wonders what, in the minds of the district’s leadership, the purpose of high school actually is. Is it merely to get credits—or to get an education?