By Tim Simmers

There’s an eviction epidemic spreading in this country that’s driving families into a cycle of poverty they can’t escape, according to author Matthew Desmond, who’s book Evicted won a Pulitzer Prize in 2017.

Speaking in Fresno last month, Desmond painted a bleak picture of the human wreckage of home evictions, describing cruel scenes such as a family standing in front of their home freezing in the cold with all their belongings in the street and their children trembling and scared.

“Eviction is a cause, not just a condition of poverty,” said Desmond, a Princeton University professor and sociologist. He spoke at the Warnors Theater in early November, addressing a stirring crowd eager to hear his insights as a standard bearer on writing about poverty and how profits continue to be made on poverty in America and what to do about it.

Evictions are on the rise in the San Joaquin Valley, too, leaving many families devastated. In Madera in late October, some 30 families were evicted without reason from their apartment complex, receiving 60-day notices. A number of tenants lived there for years. Some believed the apartment’s new owners planned to raise rents and renovate the complex. Others blamed the eviction notices on a state law that aims to cap annual rent increases at 5% in January.

“Eviction pushes families deeper into disadvantage,” said Desmond, whose book Evicted reached the New York Times national bestseller list and won numerous national book awards.

People evicted from their homes see their lives fall apart, he added. They move into smaller places, often in the poorest neighborhoods, or they end up homeless on the streets. If they get another house or apartment, it could have a hole in the roof, a broken toilet, tattered carpets or no hot water.

Desmond tells the story in his book of eight low-income families in Milwaukee trying to keep a roof over their heads. He lived with them in a trailer park and followed their lives. They sometimes lived without hot water, or their places were in disrepair.

“Eviction leaves a deep, jagged scar on the next generation,” he stressed. It’s particularly hard on women and children, and nobody can make good decisions under that kind of pressure.

There are no easy solutions. Still, Desmond insists it should be a right to have housing and likens it to “life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.”

He calls for the expansion of Section 8 housing and vouchers to help the evicted and homeless pay for rent. “When people get vouchers, they can relax and buy more food and the kids get stronger and stay in school,” he said. “They often don’t get enough to eat because the rent’s due.”

He also urged that more lawyers be available to help people getting evicted. Also, more people need to welcome affordable housing in their area.

To raise more money for Section 8 housing, Desmond recommends a controversial idea: reforming the mortgage tax breaks that many homeowners receive. Those tax breaks represent some $170 billion a year (2008), he said. He suggested using some of it for housing assistance.

In his talk, Desmond highlighted the story of Arleen from his book. She was evicted because her son threw a snowball at a passing car, and the driver got out and kicked in her front door. The landlord evicted her, sending her on a nightmarish search for housing. She called about 80 people for a rental and finally got a tiny, rundown apartment.

When she moved into the one-bedroom place, she collapsed in exhaustion on the floor for a long time as her two sons—Jori, 13, and Jafaris, 5—snuggled up to her and comforted her. For that apartment, she spent 88% of her $628 welfare check.

The national goal was once for people to spend 30% of their income on housing. Today, many spend 70% or more on rent and utilities. Under those conditions, it doesn’t take much of a mistake to get evicted, Desmond said.

A heating bill that needs to be paid can set it off. A pressing car payment or medical bill can turn a household on its head.

In researching his book, Desmond followed people evicted from their homes to the courthouse. Most were Black, Hispanic or other people of color living on the margins, or White people on the edge. For the low-income people he wrote about at the trailer park, Desmond sometimes fed and watched their children.

He also interviewed landlords and went to court with them.

Unfortunately, poverty has become a lucrative business with “no moral compass or ethical principle,’’ Desmond lamented.

Landlords have their tricks, he added. One took off the front door of a rental unit targeted for eviction. Another short-circuited the electricity, creating more psychological tension and instability.

“Poverty seems to be OK with America,” he told the crowd of a few hundred. For people facing eviction, Desmond helped set up a Web site (Justshelter.org), which identifies who can help in your area.

Desmond said that we’re witnessing the worst housing crisis in America in half a century. To add some perspective, he compared the eviction epidemic to the opioid crisis, stressing that there are 36 evictions for every deadly opioid overdose in America.

No doubt, he said, some eviction victims have made bad decisions—smoking crack or getting addicted to other drugs or alcohol. He urged compassion rather that criminalizing them.

Proceeds from Desmond’s book have been partly earmarked to aid the eviction victims he followed and lived with, helping to send their children to college and pay medical bills.

In a Q&A after the talk, attendees thanked Desmond for opening the conversation about eviction and poverty. One woman asked if any city council members were in the house. Nobody answered. “Where’s the mayor,’’ she said, raising her hands in disgust.

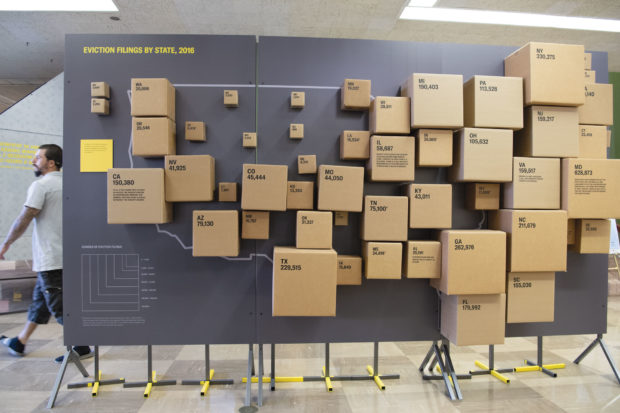

(Author’s note: There’s currently an “Evicted” exhibit at the Central Library in Fresno. Inspired by Desmond’s book, it graphically illustrates the reasons behind eviction and how better to understand why it happens. It is on display through Dec. 30 at 2420 Mariposa St.)

*****

Tim Simmers was a longtime journalist with the Bay Area News Group (San Mateo Times, Mercury News, Oakland Tribune and others) who recently relocated to Fresno.