By Stan Santos

In the Central Valley, the “water crisis” has been the focus of increasing debate and calls for action. It is a historic problem dating back generations, and an unfolding drama full of falsehoods and truths, villains and heroes, land barons and, of course, water wars. One consistent reality for farmworker families is that regardless of the outcome, they continue to be exploited and live in poverty.

According to the San Jose Mercury News, “The Central Valley, home to the world’s largest swath of ultra-fertile Class 1 soil, is the backbone of California’s $36.9 billion a year, high-tech agricultural industry. Its 6.3 million acres of farmland produce more 350 crops, from fruits and vegetables to nuts and cotton, representing 25% of the food on the nation’s table” (“California Drought,” March 29, 2014).

In 1933, the Central Valley Project was designed to move water from where it is abundant to where it is needed. The Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta channels water from the Sierra Nevada, the Coastal Ranges and high volcanic plateaus. According to the U.S. Geological Survey, the Delta has 40% of the land area of California and 50% of the total stream flow. It irrigates 5 million acres of crops, provides water to two-thirds of California’s population and is a source of hydroelectric power.

Water Turns to Gold

Public investment in massive water projects and modern technology combine to produce profit. But many products for national and international consumption still rely on the calloused hands and bent backs of farmworkers. And there is continuing tension between competing corporate interests and the needs of some of the poorest communities in the United States.

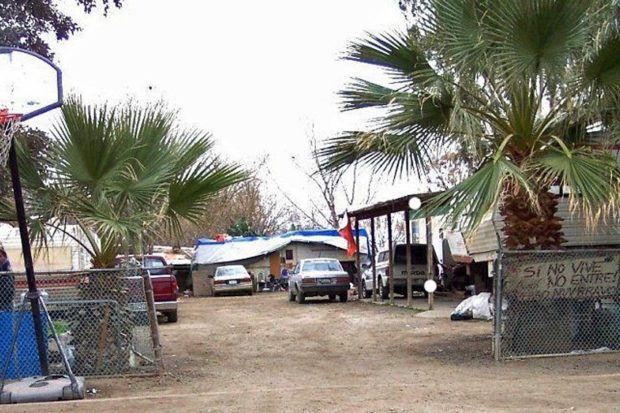

Behind the wealth and natural beauty of the Valley landscape there are thousands of dilapidated houses and trailers surrounding towns like Delano, McFarland, Huron, Mendota and Firebaugh. For farmworker families, the valley of riches is the valley of their poverty. These communities live in the most extreme poverty that can be found in the nation.

According to the 2012 Census, Fresno, Modesto and Bakersfield-Delano represent three of the five regions in the United States with the highest numbers of poor, with Fresno placing first. For Huron and Mendota, two of the hardest-hit communities, Census data placed the per capita income in 2012 at $8,026 and $8,947, respectively. McFarland’s per capita income was $8,992. In drought years, unemployment can surge to 50%. One in four children lives in poverty.

In the third year of the worst drought in its history, data cannot capture the level of suffering and its effects on Valley communities. What is clear is that during good times and economic downturns, Ag has profited while farmworker families have gotten poorer. As the recession was tapering in 2009, unemployment in Merced County was 22% and water was being rationed; agricultural revenues were the third highest in history.

Drought Impacts

On May 19, 2014, the California Department of Food and Agriculture published the Preliminary 2014 Drought Impact Estimates in Central Valley Agriculture, which points to disproportionate effects.

While water deliveries were reduced by 32.5%, or 6.5 million acre-feet, they were offset by 5 million acre-feet of groundwater pumping, leaving a shortage of only 7.5%, or 1.5 million acre feet.

Crop revenue loss in a $25 billion market will amount to only 3%, or $740 million.

Most of the economic effects and job losses are borne by the San Joaquin Valley (Fresno) and Tulare Lake basin, with a multiplier effect on economic activity.

Of 152,000 jobs directly involved in crop production, there was a loss of 4.2%, or 6,400 jobs.

Including indirect job losses, the total persons affected were 14,500.

Again, in bad times, Ag interests suffer less than the workers and the poor communities that provide their labor.

Some Actors in the Central Valley

According to the San Jose Mercury News, the following represents a few actors in the Ag industry:

- J.C. Boswell Farms—founded in 1927 by the man once known as the “King of California”; recently drilled five wells to a depth of 2,500 feet, providing a huge advantage over their neighbors in access to water.

- Paramount Farms—the largest almond grower in the world; recently converted 15,000 acres in Madera County to almond orchards.

- John Hancock Agricultural Investment Group (HAIG)—in 2010 bought the 12,000-acre Triangle T Ranch in Los Banos, known for prize-winning Hereford beef cattle, cotton and alfalfa. HAIG, with headquarters in Boston, manages investments in several states, Canada and Australia, emphasizing the globalization of the Ag industry; converted the lands of the Triangle T Ranch to almond orchards

- Trinitas Partners—a Silicon Valley investment corporation that is converting 6,500 acres of pasture land in Stanislaus to almond orchards

Why Almonds?

California produces 60% of the global supply of almonds. Investors in pursuit of profits have accelerated the conversion of crop fields to nuts, with almonds increasing 20,000–30,000 acres each year. According to the Almond Board of California, 71% of almonds are for export to China, India and other countries. A University of California Cooperative Extension adviser estimated profits from one acre of almonds at $3,510 per year—much lower than fruits and vegetables.

In regard to water consumption, it takes more than a gallon to produce each almond and three quarters of a gallon per pistachio compared to grapes, which consume a third of a gallon, and strawberries, which consume less than half of a gallon. That adds up to an average 1.3 million gallons of water per acre of almonds.

A Diversified Economy

What is also underreported is the analysis that Valley poverty is a structural problem due in large part to the lack of a diversified economy. There are not enough jobs outside of the agricultural sector, and work in the fields provides low incomes, with the exception of management. In fact, the vision for the Central Valley Project was for smaller-scale farms and diversified economies rather than total dependence on agriculture, much less huge expanses dominated by mono or singular crops for export.

According to the conservative American Farmland Trust, “Many leaders believe the key to improving the livability of the Valley is to diversify its economy, so that it isn’t as dependent on a single industry: agriculture.” It goes on to acknowledge, “No doubt, that is the direction in which the Central Valley is headed, and probably for the better.” It makes clear that future generations will prosper when they end their codependent relationship with the Ag industry.

A “Grass Roots” Movement

The California Latino Water Coalition was launched in 2007 with well-known personalities, including comedian Paul Rodríguez and Orange Cove Mayor Victor Lopez. A 2009 report by the Sacramento-based Capital Weekly found the Coalition was registered as a nonprofit organization with the Secretary of State by the influential lobbyist George Soares. His extensive list of clients included the California Rice Commission, the California Cotton Ginners and Growers Associations, the Friant Water Authority, the Nisei Farmers League and the Grape and Tree Fruit League. In the first half of 2009, as the Coalition was taking off, Soares was paid $580,000.

The Coalition organized various marches and demonstrations, the largest on July 1, 2009, with an estimated 4,000 farmers and farmworkers. Aside from targeting endangered species, they are demanding taxpayer dollars for more cheap water for Ag, although it will come at a steep price for future generations.

Farmworker movement leader Dolores Huerta said that the California Latino Water Coalition is a front group representing Ag interests. The New York Times published a report that the “activists” were paid by their bosses. In one interview, Arturo Rodriguez, United Farm Workers president, said, “In reality, this is not a farmworker march. This is a farmer march orchestrated and financed by growers.”

In 2014, the crowds mobilized by the California Latino Water Coalition had shrunk. On March 26, the Fresno Bee reported about 1,000 people turned out for a water rally held in Tulare. Nonetheless, in November, the efforts of the Ag industry and their collaborators to change the water map of California are poised to win a big victory. Voters will decide on the investment of $11 billion in infrastructure, which includes canals, tunnels, pumps and the restoration of areas that have suffered environmental damage. Many believe those areas can never be restored.

It is unknown whether this story will end for the good or ill of future generations. What is certain is that there is no legislative remedy that can make the precious liquid fall from the sky and you cannot store and distribute what you do not have. And the conditions of marginalized communities and farmworker families who have lived in constant poverty while they produced riches with their hands will likely remain as they have always been. Hopefully, one day they will enjoy a life with justice and dignity or their children will escape the valley of their poverty.

*****

Stan Santos is an activist in the labor and immigrant community. Contact him at ssantos@cwa9408.org.