Creating universal literacy and an environment where education is universal and free and accessible at all levels leads to a cultural flowering so extensive and deep as to be perhaps better characterized as an explosion. When culture, both in the sense of the cultural arts and the essence of the thought and feeling of the people, including memory, history, heritage and values, is viewed as a prime necessity rather than as an adornment, profound changes occur.

One of the greatest achievements of the Cuban Revolution has been and is the democratization of culture.

In 1998, while Cuba was still in the grip of the so-called Special Period—the period of economic depression produced by Cuba’s loss of trading partners after the end of the Soviet Union and its Eastern European allies, coupled with increased attempts by the United States to isolate Cuba and cut off all trade—Fidel Castro said, “Lo primero que hay que salvar es la cultura” (“The first thing we must save is culture”).

Now that the combination of the ravages of the pandemic and another period of increased U.S. sanctions and heavily successful attempts to isolate Cuba economically, cutting Cuba off from international trade and finance, has created another period of hardship for the Cuban people, culture is still seen as a necessity.

Pre-Revolutionary Cuba

In 1953, in Cuba only 56% of children ages 6–12 were enrolled in school, and this hides a huge urban-rural disparity. The basic literacy rate of urban dwellers was about 90%, whereas that of rural people was roughly 60%, and about half the Cuban population was rural in 1950. A 1950 study by the World Bank found that 60% of rural residents and 40% of urban residents were undernourished; 40% lacked regular, full-time employment; and 40% had never attended school.

The last in line for educational, cultural and occupational opportunities were rural Black girls. The experience of my friend Justina Temozán, from La Curva, in Holguín Province, who went to work at age eight helping in the coffee harvest, is typical. (You will be glad to know that she says, “After the triumph of the Revolution, I began to study in night school, near my house, in Gertrudis de Avellaneda, in Marianao, and I was able to get to sixth grade.”)

Changes with the Revolution

“Before 1959, it was the countryside versus the city,” according to Luisa Yara Campos, director of the National Literacy Museum, in Havana.

“The Literacy Campaign united the country because, for the first time, people from the city understood how hard life was for people before the revolution, that they survived on their own, and that as people they had much in common.”

Many of the literacy volunteers also remarked that the learning and teaching was a two-way process. One remarked, “I think I learned more from them than they did from me, because I gave them the light of learning but they taught me how to be a person.”

Another said, “It gave us the values with which we’ve lived our lives ever since. And for those of us who were women, it liberated us; our entire generation of women gained a completely different perspective of life. The Literacy Campaign changed the meaning of life for Cuban women.”

Cuban poet Nancy Morejón joined the campaign when she was still a student. She said, “An irreversible phenomenon began…I did not imagine that, years later, my efforts from 1961 would contribute to multiplying the number of Cuban readers who could not only express themselves freely but also, and above all, who could broaden their intellectual and existential horizons irreversibly.”

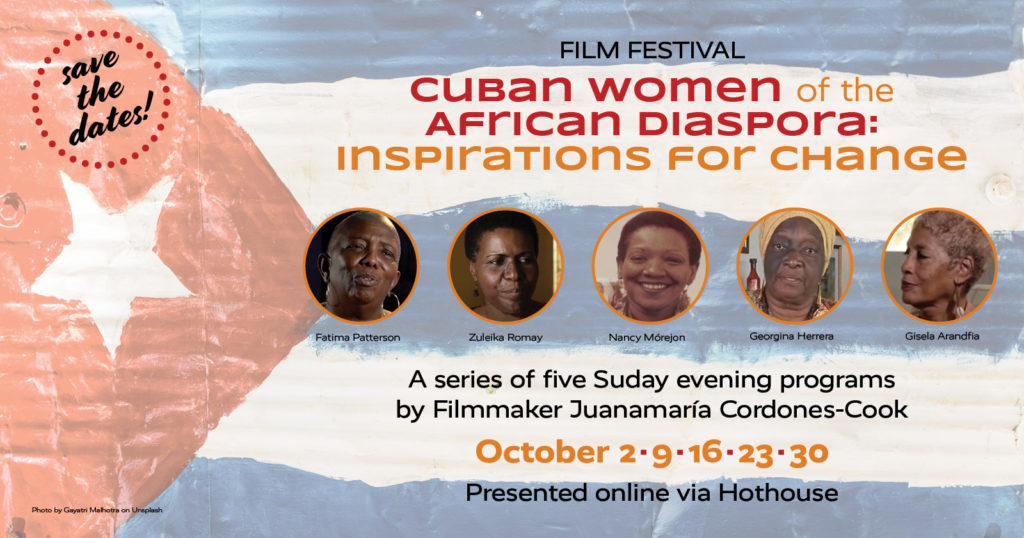

Inspirations for Change

Morejón, as a major poet and an Afro-Cuban woman, is central to the Cuban Women of the African Diaspora—Inspirations for Change project. This series of five film programs with discussion will be presented online, via Hothouse, on Sunday evenings in October, showing some of the many films made by Juanamaría Cordones-Cook, University of Missouri professor and Emmy-nominated filmmaker, who has built her scholarship around the related and complementary areas of gender studies, Afro Latin-American theater, the Afro-Cuban renaissance and documentary filmmaking.

- In the film Paisajes Célebres, Morejón offers a unique perspective on contemporary Cuban culture and intellectual life, with other outstanding Afro-Cuban intellectuals who came of age with the 1959 Cuban Revolution.

- Poet Georgina Herrera is featured in two films, Cimarroneando con G.H. and a testimonial documentary, discussing memory, gender, race and Black rebellion.

- Playwright and director Fátima Patterson explores race, gender and African popular religion through theater and oral history in the film Race, Gender and Theater.

- There’s more. This is an opportunity to see how Cuban women of the African diaspora have seized the opportunity to define culture and make it glorious.

The primary sponsor of this project is WILPF-US; other sponsors include U.S. Women and Cuba, the Literacy Project, Code Pink, the National Network on Cuba, the Southern Anti-Racism Network and Teatro de la Tierra.