Dr. James Turner, the founder of Africana studies, has passed away at the age of 82. He was the founding director of Cornell University’s Africana Studies and Research Center and a professor emeritus of African and African American politics and social policy in the College of Arts and Sciences at Cornell.

For more than 50 years, Turner taught and shaped generations of Black scholars and a diverse population of students. He had a multidisciplinary approach to exploring constructs pertaining to the African diaspora. His approach created a template for teaching Africana/African American studies that has spread throughout the world in articulating the Black/African diaspora experience.

He was a mentee of the great Pan-Africanist and historian John Henrik and was in the audience of several Malcolm X lectures in New York City.

“Malcolm was a master teacher,” Turner said. “You couldn’t listen to him and not come away with something. It was more than charisma; it was the way he was able to use the language of our people and make (them) understand.”

Turner earned a master’s degree in African studies from Northwestern University, a certificate in African studies from Northwestern’s African Studies Center and a Ph.D. from Union Graduate School in Cincinnati.

As a graduate student and after completion of his doctoral studies, Turner was an activist and an intellectual thinker. Because of his activism, Cornell offered him a position to lead the Black studies center.

Turner accepted the position in 1969 and indicated that his goal was to make the center “one of the most far-reaching, imaginative and creative programs in the country.” His vision was based on the demands of Black students who wanted to learn more about their history and how Africans/African Americans shaped America.

As we look back at Turner’s vision, we observe that the center was originally called the Center for Afro-American Studies, but Turner’s vision was more global. Although the term Africana had been used by African and African American scholars of that time, such as W.E.B. Du Bois, the term gained momentum when Turner used it to define the global experience of all African descendants who are a part of the African diaspora.

“In Africana studies, you cannot dissect it and say, well, here is a little piece of history, here is another section of the literature, here is the sociological part of your contribution, here is the psychological, here is the political,” said N’Dri Thérèse Assié-Lumumba, professor of Africana studies and director of the Institute for African Development.

“You hear now about interdisciplinarity; well, African studies, with Professor Turner’s conceptualization, was the precursor.”

This was and is Dr. Turner’s legacy in the academic discipline of Africana/African American studies.

When I was a student at Fresno City College in 1969, I was part of a group of African American students who demanded that the college hire an African American instructor to teach Black/African American history. The college hired Kehinde Solwazi in 1971 as a full-time instructor to teach Black history and some related courses leading to an associate of arts degree in cultural studies.

The program now leads to non-transfer or transfer degrees in African American studies. Solwazi retired two years ago after teaching Black/cultural and African American studies at Fresno City College for 50 years.

As Turner did at Cornell, Solwazi taught many African American and non–African American students during his long tenure at Fresno City College.

In my opinion, Africana/African American studies can also be viewed as follows:

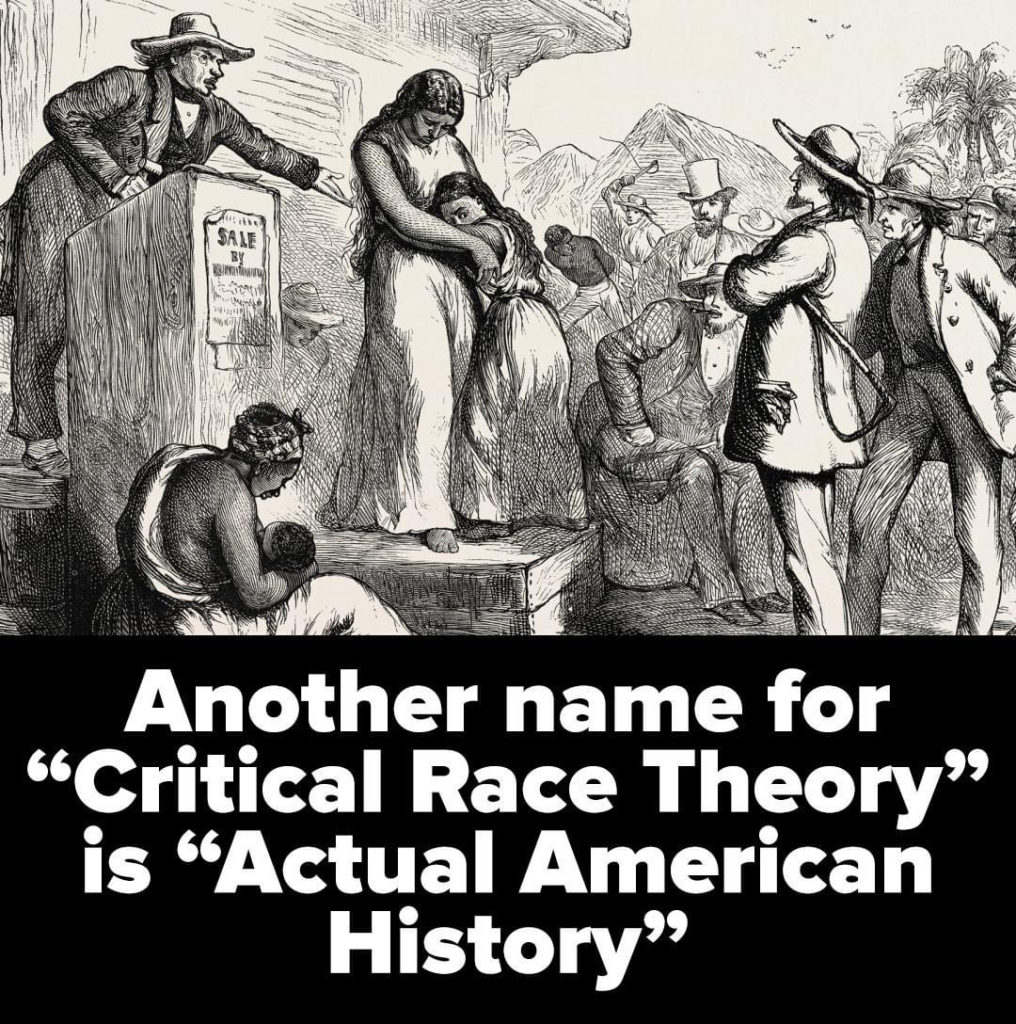

- Telling the histories of Africans in the diaspora through the gaze of critical race theory (CRT)—research, theories and arguments into how racism, White supremacy and governmental policies were used to thwart the economic, political and social advancements of African Americans and Africans in the diaspora.

- Telling the stories of Africans in the diaspora through the gaze of critical resistance theory—research, theories and arguments into how Africans and African Americans have been fighting White racism and White supremacy before 1619 and after this date to make America a more just, inclusive, diverse and democratic nation.

- Telling the history of African Americans through their gaze of interpreting historic events and movements that African Americans were either a part of or leaders of and their goal to make America a more perfect union.

As we all know, African-American history is also American history.

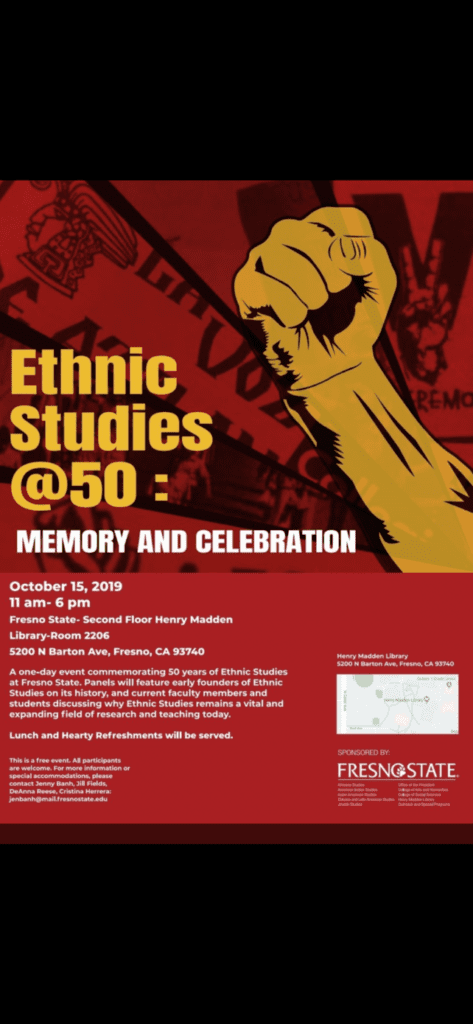

I attended an event at Fresno State in October 2019 titled “Ethnic Studies @50: Memory and Celebration.” It was a one-day event commemorating 50 years of ethnic studies at Fresno State. Here are some of my thoughts and observations on this event.

It was good to hear the different historical developments of ethnic studies at Fresno State. I am sure that similar developments happened at other American colleges and universities. Similar developments happened at Fresno City College and other California community colleges. I also liked the overview of how the name of a specific ethnic studies program has changed over 50 years: Black studies, African-American studies, Pan-African studies and Africana studies.

As I reflect on the presentations, I would like to posit a simple dialectical analysis upon the development of ethnic studies over 50 years.

Thesis. Education in America was developed to educate the sons and daughters of those who were White and could afford an education. The historical focus of education prior to the Civil War and after was the glorification of historical accomplishments of White people or European Americans. This pedagogy can also be identified as a Euro-centric approach to education in America.

Antithesis. As more and more people of color were permitted to study at White dominant colleges and universities, the question arose as to where were their historical accomplishments recorded in the history that they were being exposed to—an Afro-centric argument as to how academics and the academy interpret and analyze history.

For African Americans, if you were not attending a historically Black college or university (HBCU), you would get a primarily whitewashed telling of your historical participation in the development of America and your contributions to world history.

Because of the Black power movement, the Black community started demanding courses and historical investigations and analysis that indicated African American contributions to the development of American idealism and African and African American contributions to the development of world history and American history. That led to the arguments for and the development of ethnic studies programs on the campuses of American colleges and universities.

Ethnic studies programs challenged the traditional Euro-centric teaching at American colleges and universities. These programs also enabled the training and hiring of instructors and professors of color to teach these courses, which presented a challenge to Euro-centric pedagogy.

Synthesis. A pedagogy in American education surfaces in which there is the development of a world-centric approach to teaching history—an analysis and interpretation of the contributions of all people of color and their historical influences toward the development of American idealism: Native Americans, Latin Americans, Asian Americans and African Americans.

The interpretation and analysis of historical periods in America highlights historical developments and the reaction to these developments by non-White or by White people. Basically, we see the historic struggle of non-White people against the ideology and philosophy of White supremacy.

This educational approach should start at the grade-school level and proceed in an orderly and structured manner all the way through high school. This way, an American student will not have a Euro-centric education but rather a people-centric education that includes all ethnic groups in the telling and documentation of American and world history.

Colleges and universities can keep their ethnic studies program, but based on this pedagogy, when students enter a college or university, they will have an objective view of their ethnic history and their contributions to American and world history. Then the college or university, through ethnic studies classes, will expand on this knowledge. The goal is for students not to be encountering this historical information for the first time at the college or university level.

Basically, this synthesis would be for the development of a pedagogy for America that will provide to American citizens a true historical telling of what it means to be an American and the ethnic and cultural contributions to American idealism by all Americans.