Photo Essay by David Bacon

(Editor’s note: Photojournalist David Bacon visited Fresno in November 2022. He walked around downtown Fresno and captured some special moments he now shares with us. His work has been supported by the Economic Hardship Reporting Project.)

In the most productive agricultural area in the world, poverty is endemic. Crisscrossed by irrigation canals and railroad tracks, Fresno is the working-class capital and largest city of the San Joaquin Valley.

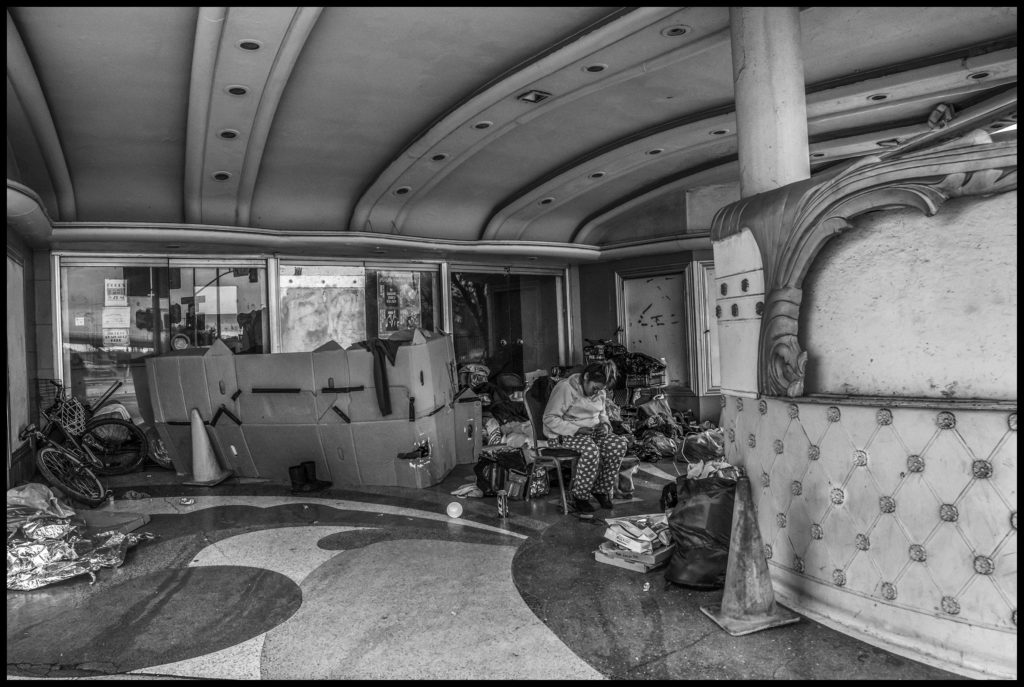

The polarization of rich and poor is a constant theme in the city’s history and in its present. The banks and growers of the Valley built ornate office buildings and movie palaces when the downtown was their showplace. Now, as developers have abandoned downtown for the suburbs, the theater entrances and building doorways have become sleeping spaces and refuges from the rain for those without a home.

Fresno has one of the oldest Mexican barrios in California. Here, the abandonment is visible in closed theaters and dance halls, which leave their marquees as vestiges. Alongside them are small taquerias trying to survive. Today, the street in front of the Azteca Theater is hauntingly empty at night, but older residents remember when Cesar Chavez and a column of grape strikers stopped in front on F Street in 1966.

Bisecting downtown are the railroad tracks and the old Highway 99: a defining geography for the settlements of unhoused people. Community activists and the homeless people in the area have pressured a normally intransigent city government to provide at least enough housing to keep the dream of life off the streets alive.

In 2019, Fresno had a larger percentage of “unsheltered” homeless people than any other city in the country—that is, people sleeping on sidewalks, in cars or in places the government calls “not suitable for human habitation.”