Yaroslava, the wife of a Ukrainian prisoner of war, is a warrior. For months, she’s been struggling to liberate her husband of 30 years, a father of her four children and grandfather of four grandchildren, and Azov regiment fighter.

Mykola is kept by the Russian military in a pretrial detention facility in Olenivka, in the Russian-occupied Donetsk Oblast. Yaroslava’s two sons-in-law, the fathers of her four grandkids, are also there. All three men defended the Azovstal plant in Mariupol.

The Russian occupational forces besieged Mariupol, a city by the coast of the Azov Sea, in March 2022, soon after the start of the full-scale invasion in Ukraine. The Azov regiment, a unit of the National Guard of Ukraine, founded in 2014 as a volunteer paramilitary militia to defend Donbas from the Russian invasion and fight pro-Russian forces, fought for the city but by early April, retreated to the bunkers of Azovstal, a steel plant.

On May 17, following the order of the Ukrainian president and commander-in-chief Volodymyr Zelenskyy, after almost three months of fierce resistance, more than 2,500 defenders surrendered to the Russian military. Most were sent to Olenivka, and only a few were exchanged for Ukrainian POWs.

Russia threatened to hold a tribunal for the Azovstal defenders, labeling them “Nazis.” Vyacheslav Likhachev, a historian and a member of the Expert Council of the Center of Civil Liberties, explains that the Azov regiment has disassociated with the ultra-right movement.

Families, who have not heard anything about their loved ones for months, appealed to the international community leaders to demand an exchange. They have addressed the Pope and the Chinese and Turkish presidents but to no avail.

On July 29, a powerful explosion shook Olenivka, killing 53 Ukrainian POWs. Russian proxy state authorities and the Kremlin-funded press claimed that the Ukrainian military used a U.S.-made HIMARS rocket to kill their own servicemen to “prevent them” from talking about alleged war crimes.

Ukrainian authorities denied the claims and accused Russia of committing a terrorist act to hide the evidence of torture. Based on the situational analysis, independent Western military experts and CNN journalists concluded that the Russian version was likely a fabrication.

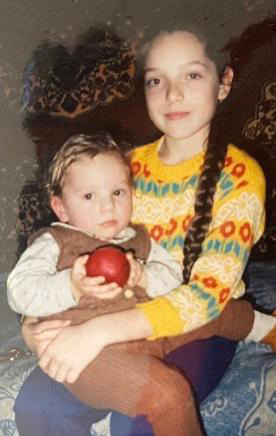

I first met Yaroslava and her two older daughters in a small village in the Cherkasy region. As we walk along the shadowy main street past a dusty World War II monument commemorating Soviet soldiers, the women tell me their love stories: simple, wholesome, almost trivial as most stories of a happy and peaceful life.

Meeting at dance parties in their villages, going to the capital city, Kyiv, to work odd jobs to make money for wedding rings, returning home to raise children next to their parents, moving to Mariupol as a clan, taking kids to karate and ballet classes and dreaming of getting a French bulldog puppy.

Yaroslava’s story is somewhat different, though. A native Russian from Siberia, she met her Ukrainian flame at 19, dropped out of college, followed him to Ukraine, and stayed for life. Her birth country has now attacked her chosen country, drove her from home, and took her and her daughters’ men away. Her only son, also an Azov regiment soldier, was injured at war.

A bright blonde with piercing blue eyes, she speaks Ukrainian, telling me about her husband’s love “for his land, rivers, lakes, mountains.” I am reminded of Yaroslavna, one of the main characters of the medieval epic poem “The Word about Igor’s Regiment” (usually translated as “The Tale about Igor’s Campaign”), written in the late 12th century.

Prince Igor and his son were taken prisoners during a war campaign. His wife, Yaroslavna, climbed the city wall and called to the wind, the sun, the Dnipro for help. Her chants worked magic: birds, animals and the soil itself brought her prince home and the joy spread all the way to Kyiv.

The complex beauty of the epic poem matches the debates about its origin, authorship and national “ownership.” Russia claims the epic poem along with the lands that inspired it. Back at the hotel, I reread Taras Shevchenko’s Ukrainian translation of the song in the Old East Slavic language, “I will fly like a cuckoo bird, I will zigzag, I will wash his bloody wounds with my sleeves.”

Yaroslava’s two older daughters are quiet, with beautiful black hair and sad eyes. Like their mother, they married young and dedicated themselves to raising children. Anastasiya tells me that her husband was crushed by what the Russians did in Mariupol, bombing buildings, burning alive women and kids inside.

“Dmytro just wanted to defend them,” she says, crying. “He’d visit, bring them food and toys, and next day nothing’s left, just ashes…Nazis are those who came here to kill our children.”

Victoria is more reserved. Her husband was injured during the explosion in Olenivka.

“I saw Oleksii’s name on the list of wounded. We don’t know if we can trust these lists.”

Other than that, the family knows nothing about the fates of the men. Russia does not share any information with the Ukrainian authorities or international humanitarian organizations such as the United Nations or the Red Cross.

Matilda Bogner, the head of the UN human rights mission in Ukraine, said that “Russia is not allowing access to prisoners of war, adding that the UN had evidence that some had been subject to torture and ill-treatment, which could amount to war crimes,” as reported by Reuters.

Over the next month, I met dozens of Azovstal women—mothers, sisters and wives of the Azovstal defenders. Not everyone wants to be recorded, but each one is determined to find and free her loved one.

Natalya from Mykolaiv organizes a photo exhibit in Kyiv and tells me about her brother’s passion for art, photography and painting, her brown eyes brimming with tears.

Another view of the photo exhibit. The wife of one of the Azovstal defenders praying in front of her husband’s photo.

Kateryna Prokopenko, the wife of the Azov commander, Lieutenant Colonel Denys Prokopenko, awarded the title “The Hero of Ukraine” by President Zelensky, sits down to talk to me on Aug. 24, Ukraine Independence Day, in Kyiv. Fit, hip, wiry, an athlete and an artist, Kateryna shares her romantic story: Denys proposed to her as they were backpacking in Scandinavia, presenting a ring “brought by a troll.”

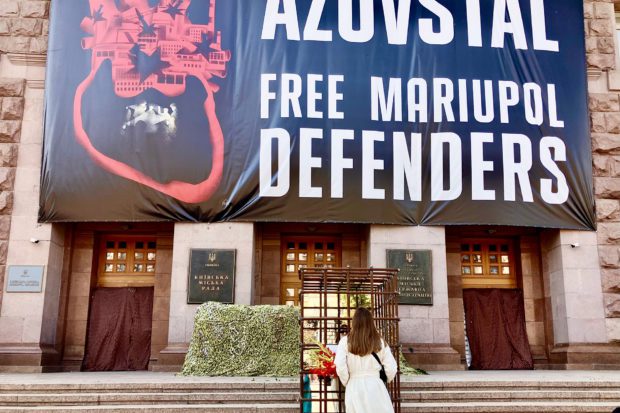

As the air raid sirens howl nonstop, Kateryna shows me her animation art: signature cartoon goats and birds. Then, she leads me to a human cage she designed as a replica of the metal cages built by the Russian authorities for the tribunal intended for Azov fighters. Her “cage” is installed at the main street of Kyiv, Khreshchatyk, with a mirror inside, “so you can imagine how it feels.”

Lisa was getting ready to marry the love of her life when the war started. She can’t find her fiancé and has not heard from him for months. “The war ruined all plans,” she says.

“I had a dream the other night that I got him out of prison and carried him in my arms all the way home…We are ready to shout to the whole world—no, to the whole galaxy—help us free them!”

I met Yaroslava again in Kyiv, a month after our first meeting, and she and her daughters are heading to protest by the President’s office. They still have not heard a word about their husbands.

“Why can’t the whole world stop one person? Why can’t we stop the war? Is the whole world helpless against Putin? Why?” asks Yaroslava.

(Editor’s note: As our press deadline neared, Zarina informed us that of the Azov fighters mentioned, only Denys and Aleksey had returned home.)