By Peter Maiden

I am the child of a survivor of the Holocaust, part of what’s known as the second generation. Whether it be nature or nurture, all my life I have experienced a sense of trauma, often without knowing the reason why. As a young child, while I heard the stories of Peter Rabbit and Benjamin Bunny, I also heard true stories about crossing borders to escape certain destruction.

My family’s history was the subject of a display marking the Holocaust Day of Remembrance (April 8) at the Woodward Park Library in Fresno. The display was up for two weeks.

Our family lived in Austria. The Nazis marched from Germany into Austria in March of 1938. My great-grandmother, Klara Wenkart, left for Italy in September of 1938, becoming separated from the rest of the family, who got out in December. Mussolini, Italy’s pro-Nazi dictator, was, for reasons of his own, uninterested in turning Jews over to Hitler at that time. In 1943, though, the Germans came to Italy and began to round up Jews to send them to concentration camps.

Klara then hid in a church for a while, but word got out, and she had to flee again. Led by a guide sent with her by a priest, she made it to an unattended area on the Swiss border and crossed over.

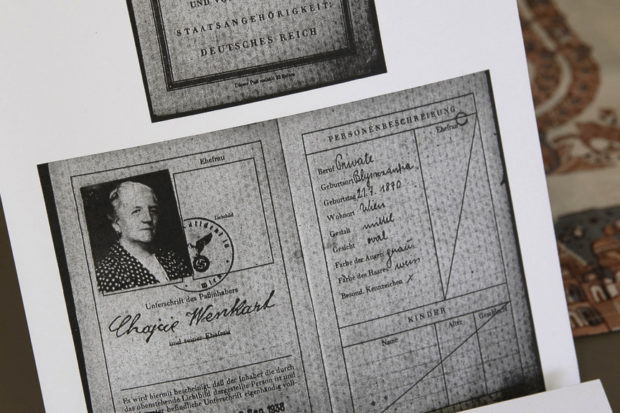

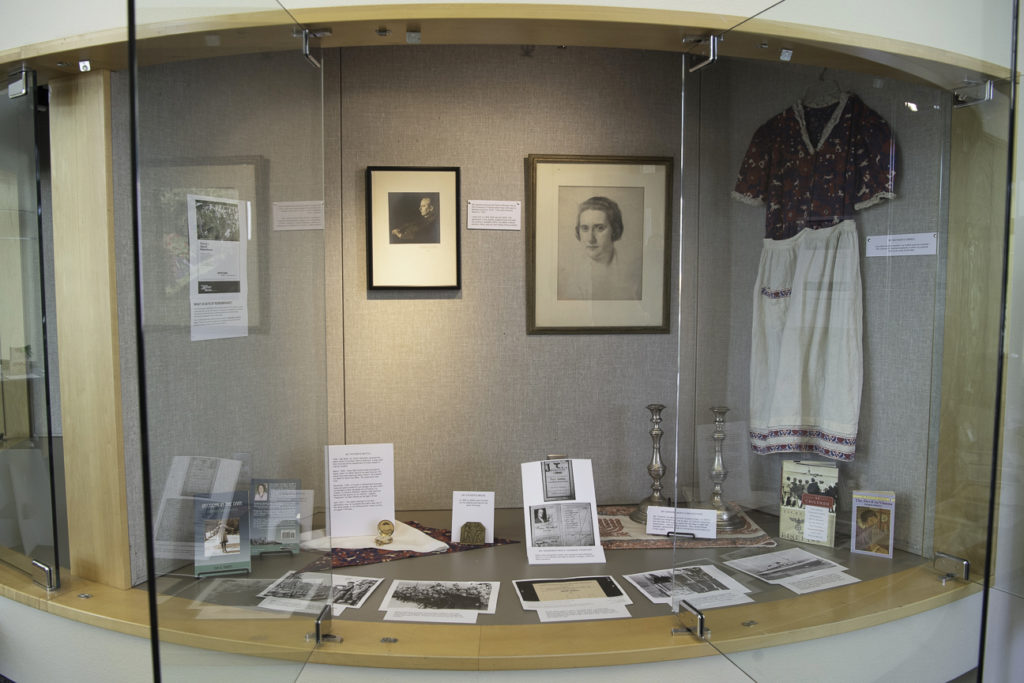

She had no papers, but in her backpack, she carried two candlesticks from her Vienna home for the celebration of the sabbath. My mother has those candlesticks now, which were part of the library display. So was a photocopy of Klara’s German passport (Austrians then had German passports), complete with swastikas, and marked with a big “J” for Jewish. Klara finally made it to New York after the war.

Before Hitler took over Austria, my grandparents, Dr. Simon Wenkart and his wife Dr. Antonia Wenkart, had a good life in the capital, Vienna. They had come to Vienna from Poland to improve their situations, and they both became medical doctors there. They had two children: my uncle Helmut, born in 1930, and my mother Eva, born in 1935. Their offices were in a large apartment where they also lived. Simon was a coroner and had a part-time family practice.

On display at the library was a gold watch, which Simon got from his employer at the public health department when Helmut was born. There was also a boxing medal, which he received in 1926 for supporting boxing as a ringside doctor.

Simon was treasurer of the Socialist Party of Vienna. Vienna had a socialist municipal government, but all that was over quickly when the Nazis came. Simon showed up at work and his boss was wearing a Nazi uniform, asking “Is that Jew Wenkart still working here?” Family legend has it my grandfather’s hair turned white overnight.

A patient of my grandfather’s worked as a secretary at a police station, and he received a call from her. She said, “Herr Dr. Wenkart, I was typing a list of people to be arrested, and you were one of the first on it. You need to hide.” He went into hiding in the pantry of the home of a gentile doctor friend.

It became illegal for Jewish doctors to work and for Jewish patients to be treated. My grandmother, who was a pediatrician, went out at night surreptitiously to treat children. There was a scarlet fever epidemic, and she saved many children’s lives.

My uncle Helmut was arrested at the age of eight by the police, for being Jewish and playing in a park where Jews were no longer allowed. He spent a harrowing day at the police station, where he was likely tortured. He never spoke to me about it, but there were times when I could sense his pain.

After long weeks of trying to get out—as they lost all of their property and their civil rights and were coming closer and closer to losing their lives—a visa to go to Switzerland finally came through for my mother’s family. They had relatives in the Swiss city of Zürich who said they would be their sponsors. In 1938, Hitler was satisfied when Jews left German territory never to come back. Later, he killed all the Jews he could find.

My grandfather had been sick in the last days of hiding in Austria and collapsed on the tarmac of the airport in Zürich with a burst appendix. He was rushed to the hospital, where he stayed for many months.

In Switzerland, the family was not allowed to work, but my grandmother took work anyway in a candy factory. My mother and her brother were sometimes hungry, and she fed them candy at night.

Finally, the family attained a visa and tickets with help from relatives and arrived in New York in 1941. My mother’s immediate family all escaped: Eva, Helmut, Simon, Antonia and a maiden aunt named Valli. I was incredibly lucky in this regard, as I grew up with the family intact and was able to fully absorb their influence.

After the war, my grandmother became deeply depressed when she heard the news from the Red Cross that she had lost around 40 Austrian and Polish relatives in the Holocaust.

My grandparents learned English and studied to become American doctors. They had been to the lectures of Dr. Sigmund Freud in Vienna, and they decided to both become psychiatrists. By the time I was born they were settled in that profession. My mother became a school psychologist and family therapist, and Helmut became a translator.

For those who might be interested, my mother Eva Maiden wrote a memoir of her childhood, Decisions in the Dark: A Refugee Girl’s Journey. It is available as a paperback or in a Kindle version on Amazon.

*****

Peter Maiden is the photo editor of the Community Alliance newspaper.