By Laura Garcia, Michael Ballin, Carlene Merino, and Matthew Fosberg

Recent National Attention on Police-Community Relations

Highly publicized events in 2014 exposed significant fractures in the relationships between local police and the communities they protect and serve, and, in December 2014, the U.S. President’s Task Force on 21st Century Policing was established. The Task Force—co-chaired by Charles Ramsey (Commissioner of the Philadelphia Police Department) and Laurie Robinson (Professor of Criminology, Law, & Society at George Mason University)—met seven times in January and February of 2015 and held listening sessions in Washington, D.C.; Phoenix, AZ; and Cincinnati, OH with more than 100 individuals from diverse stakeholder groups—law enforcement officers and executives, community members, civic leaders, advocates, researchers, academics, and others—in addition to many others who submitted written testimony. In its “Final Report,” issued in May 2015, the Task Force identified six (6) “pillars” for the safe and effective delivery of policing services in the 21st Century: 1) Building Trust and Legitimacy, 2) Policy and Oversight, 3) Technology and Social Media, 4) Community Policing and Crime Reduction, 4) Officer Training and Education, and 5) Officer Safety and Wellness.

The Importance of Building Trust and Legitimacy

It’s not surprising the Task Force identified “Building Trust” as the first pillar: “The relationship between police departments and the communities they serve and protect has been the focus of study in criminology and related fields for decades. That work means that we understand why that relationship is important—when the public trust and respect police they are more likely to call on them for help, to cooperate with them in critical situations, and work together to solve community problems—and the value of a strong relationship for both police officers and citizens” (Jackson 2015:2). The path forward, in the view of Professor Brian A. Jackson (2015:1), is “partly about the public trusting police, but it is also about the police trusting the public. To trust and respect each other is a two-way street, and it is unlikely that the problems we face today can be solved without some distance traveled on both sides.”

“Non-Whites have always had less confidence in law enforcement than Whites, likely because ‘the poor and people of color have felt the greatest impact of mass incarceration,’ such that for ‘too many poor citizens and people of color, arrest and imprisonment have become an inevitable and seemingly unavoidable part of the American experience.’ (Stevenson 2006). Decades of research and practice support the premise that people are more likely to obey the law when they believe that those enforcing it have the legitimate authority to tell them what to do. But the public confers legitimacy only on those they believe are acting in procedurally just ways. Procedurally just behavior is based on four central principles:

- Treating people with dignity and respect

- Giving individuals “voice” during encounters

- Being neutral and transparent in decision making

- Conveying trustworthy motives (Mazerolle 2013)” (President’s Task Force:9-10).

The Culture of Policing: “Guardian vs. Warrior”

Task Force Recommendations 1.1 and 1.3 refer to changing the culture of policing—from “warrior” to “guardian”—and embracing a culture of transparency and accountability—by, for example, making all department policies available for public review, regularly posting on the department’s website information about stops, summonses, arrests, reported crime, and other law enforcement data aggregated by demographics, and establishing civilian oversight mechanisms.

Yet, on December 15, 2016, the Fresno City Council approved (5-0 with Soria absent and Baines abstaining) an “urgent” request from the Chief Jerry Dyer to spend $325,000 to purchase 270 Colt Manufacturing semi-automatic rifles to be issued to uniformed officers (Sheehan 2016).

Police Accountability & Transparency: The Office of Independent Review

People of the Fresno community have long been concerned about the relationship between the Fresno Police Department (FPD) and the public in general. Specifically, those concerns have been about racial profiling, officer-involved shootings (OIS), the loss of human life, and wrongful death lawsuits that cost city taxpayers millions.

In March 2000, in response to fears expressed by women in the African-American community that FPD was unjustifiably targeting their children while driving, the Central California Criminal Justice Committee (CCCJC) emerged from a series of informal community meetings into a network of citizens seeking greater information about the activities of the local police department. CCCJC’s purpose is “to establish a police review mechanism that will empower the community and enhance mutual respect between the police and the people.”

After a decade of organizing public forums, protests, and demonstrations, collecting and analyzing local police data, and speaking in front of City Council, Eddy Aubrey was hired as the first Independent Police Auditor (IPA) of the City of Fresno in December 2009. After a serving a short term, the City of Fresno hired Richard “Rick” Rasmussen, having just retired after serving 21+ years with the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), as IPA on September 4, 2012. In June 2015, Mark Scharman was hired as director of internal audits in the city’s Office of Independent Review (OIR), and, together with IPA Rasmussen, they review FPD’s policies and procedures and prepare quarterly reports with recommendations. Current and previous reports are available at http://www.fresno.gov/Government/CityManager/IndependentReview/Reports.htm.

Based on the City of Fresno’s website of the Office of Independent Review (OIR), “The mission of the OIR is to strengthen community trust in the Fresno Police Department by providing neutral, third-party review of police policies, procedures, strategies and internal investigations. The OIR works independently of the Fresno Police Department and provides the City’s leaders and the public with objective analysis of policing data, actions and outcomes.”

“The OIR analyzes complaints filed by citizens with the Police Department Internal Affairs Division to ensure they have been investigated fairly and thoroughly. The OIR also provides an objective analysis of individual units within the police department to ensure compliance with policy and procedure, best practices and the law. This includes recommendations on findings to increase thoroughness, quality and accuracy of each police unit reviewed.”

The OIR does not conduct its own investigations; its audits are always performed after the Police Department completes its internal affairs investigation, and the OIR is given access to the Internal Affairs investigation.

2016 Fresno OIR Quarterly Reports and Recommendations

Based on data and independent record-keeping from individuals associated with CCCJC, from 1997 to 2016, 89 FPD officer-involved shootings (OIS) resulted in death (G. Hernandez, personal communication, November 2016). Fresno’s OIR has made recommendations for department policies and procedures to reduce OIS. In the 2016 third quarterly report, IPA Rasmussen recommended FPD “make de-escalation a formal policy.”

The Dallas PD is pioneering “de-escalation tactics,” where police try to slow the action down to avoid using force. Other cities emphasizing de-escalation have seen excessive force complaints fall, including Seattle and Las Vegas. However, instead of agreeing to incorporate de-escalation tactics into formal policy, Dyer responded that “de-escalation language and techniques are interwoven into every aspect of FPD training…” (Guy 2016). A Police Executive Research Forum survey of 281 police agencies found the average police “recruit” receives 58 hours of firearms training, 49 hours of defensive tactical training, but only eight hours of de-escalation training while noting variation across academies (PERF 2015:11). “The survey [also] found that 93 percent of responding agencies provide in-service [officer] training on use of firearms, while 69 percent provide training on crisis intervention skills (for responding to calls involving persons with mental illness or other conditions that can cause erratic behavior), and only 65 percent provide in-service training on de-escalation skills” (PERF 2015:12). How many hours of training in crisis intervention and de-escalation skills do FPD officers get?

Regardless of the amount of training received, de-escalation must be embedded in departmental policies on “use of force” which outline specific rules officers are expected to follow. Seattle PD’s policy reads: “When safe under the totality of circumstances and time and circumstances permit, officers shall use de-escalation tactics in order to reduce the need for force.”

Racially-biased Policing?

Fresno’s OIR has also been able to get access to “hard-to-obtain” information provided by Fresno PD, such as data on field interviews, traffic stops, and detentions broken down by demographics (Hess 2016).

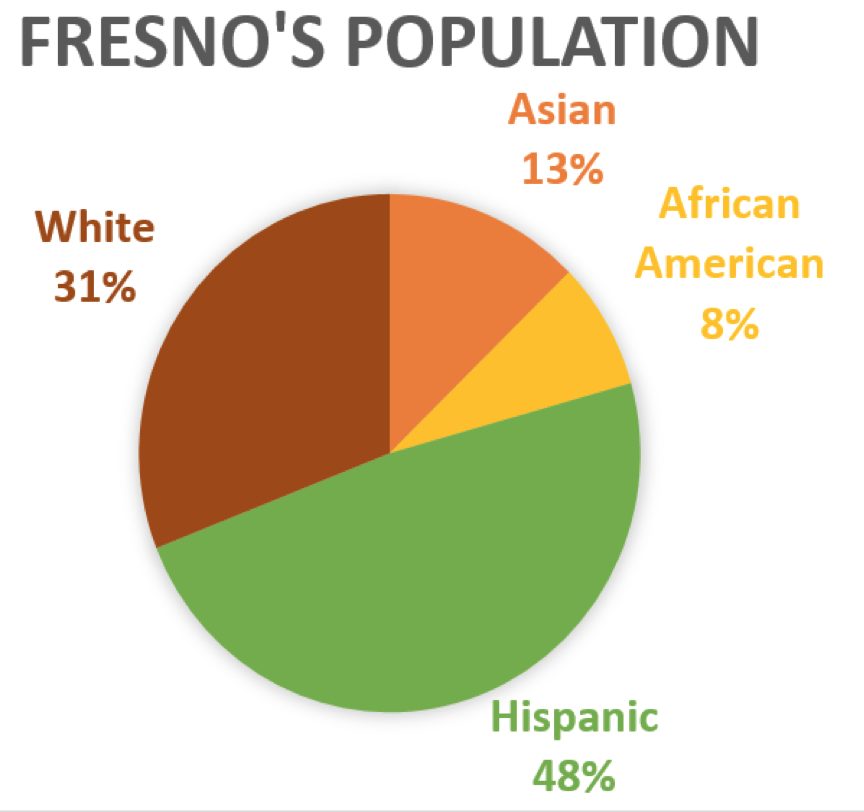

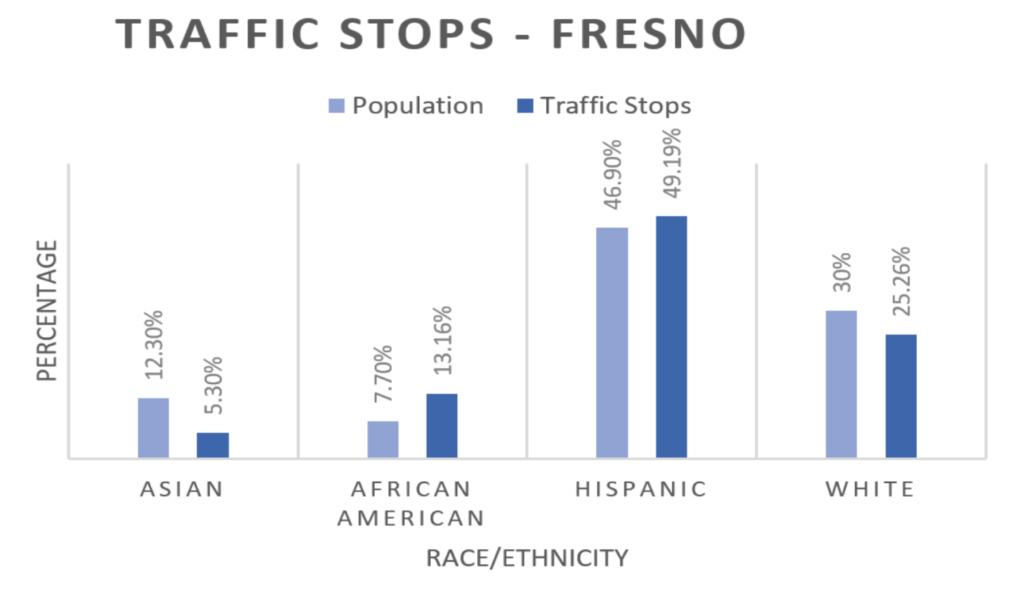

The second and third quarter reports of 2016 issued by the Fresno OIR and reveal that African Americans and Hispanics are subject to more “Field Interviews” and “Traffic Stops” than their respective proportions in the population would predict (see accompanying graphs). For example, although African Americans constitute only 7.7% of the population of the City of Fresno, they represent 13.2% of the 66,165 traffic stops and 24.4% of the 1,625 field interviews by Fresno PD. This difference is statistically significant (i.e., unlikely to have occurred by chance) and means that African Americans are 216% more likely to be subject to a “Field Interview” than their proportion of the total Fresno population would predict. Of the 1,625 total field interviews conducted, only 48 individuals were detained. However, only 3.03% and 2.42% of the Field Interviews of African Americans and Hispanics, respectively, result in arrest/detention, compared to 4.11% of the Field Interviews of whites (a statistically significant difference).

The second and third quarter reports of 2016 issued by the Fresno OIR and reveal that African Americans and Hispanics are subject to more “Field Interviews” and “Traffic Stops” than their respective proportions in the population would predict (see accompanying graphs). For example, although African Americans constitute only 7.7% of the population of the City of Fresno, they represent 13.2% of the 66,165 traffic stops and 24.4% of the 1,625 field interviews by Fresno PD. This difference is statistically significant (i.e., unlikely to have occurred by chance) and means that African Americans are 216% more likely to be subject to a “Field Interview” than their proportion of the total Fresno population would predict. Of the 1,625 total field interviews conducted, only 48 individuals were detained. However, only 3.03% and 2.42% of the Field Interviews of African Americans and Hispanics, respectively, result in arrest/detention, compared to 4.11% of the Field Interviews of whites (a statistically significant difference).

A Benefit of Fresno’s OIR: Reduced Lawsuits & Settlements

Prior to Mr. Rasmussen’s being hired with OIR, more than two dozen lawsuits alleging excessive force and police misconduct by Fresno PD were winding their way through federal court (Garcia and Neyland 2009). The price of fighting these legal battles, not to mention the payouts resulting from either settlements or findings against Fresno PD, cost Fresno taxpayers millions of dollars. According to KMPH-KFRE.COM media reports, about 180 lawsuits were filed against the Fresno Police Department between 1997 and 2009, and the city paid out about $5.7 million in settlements and judgments—$2.8 million of which were specifically for civil rights violations. Since the re-institution of the OIR under Rick Rasmussen in September 2012, there have been no payouts resulting from any complaint to date (any recent payouts were from complaints filed prior to September 2012. For example, the city of Fresno agreed to pay $2.2 million to settle a federal civil rights lawsuit [Lopez 2016] filed by the parents of Jaime Reyes Jr., 28, who was shot on June 6, 2012). The presence of the OIR can help build public trust and also save the city money.

Renewing and Strengthening Fresno’s Office of Independent Review

Although the OIR is a step in the right direction for improving the public trust of local law enforcement, research on best practices of police oversight suggests the OIR should hold more power than it currently does. Truly independent police auditors and Civilian Review Boards (CRB) “usually have subpoena power over the police and or some court mandated substitute, so they are able to obtain information without persuading police to cooperate voluntarily” (Lynch and Stone, CATO Institute). For example, Berkeley’s CRB conducts its own investigations concurrently with Berkeley PD’s IA division, thus allowing it to publish its own findings and whether it came to the same conclusion as the IA division (Lynch and Stone, CATO Institute). Additionally, the Police Commission for the County of Honolulu, HI is notable because, while it functions as a CRB, it also has the authority to hire and fire the police chief for the county (Lynch and Stone, CATO Institute). In Salt Lake City, for example, they have an Independent Investigator and a Civilian Review Board (not just “Advisory”). The Investigator conducts a side-by-side investigation with the Internal Affairs Unit of the Police Department (as opposed to “after” the IA investigation currently in place in Fresno). The Investigator participates in all interviews, has access to all evidence, and may compel witnesses to be interviewed. Once the Investigator has finished the investigation, it is presented to the Civilian Review Board which deliberates and sends a recommendation to the Police Chief regarding whether or not the complaint should be sustained, along with any other recommendations. The Police Chief has complete and final authority over all disciplinary decisions but is required to take the recommendations of the Police Civilian Review Board into consideration.

Call to Action: Sign Online Petition & Attend January 3rd Press Conference

Our team of Fresno State students has been conducting research on police oversight models and working with different organizations in the community such as Central California Criminal Justice Committee (CCCJC) and Faith In the Valley (FIV) (formerly Faith In Community) for improving police accountability to enhance the public’s trust.

We are petitioning Fresno’s Mayor and City Council to PROTECT and STRENGTHEN the existing Office of Independent Review. Our community would like to not only keep the OIR but strengthen the powers of that office to continue to monitor the Fresno Police Department, review, and preferably independently investigate, complaints of police misconduct, and make policy and procedural recommendations in order to foster greater trust between the police department and community members. We subscribe to the ACLU’s “Ten Principles” for Effective Oversight of Police: Independence; Investigatory Power; Mandatory Police Cooperation; Adequate Funding; Public Hearings; Reflect Community Diversity; Policy Recommendations; Public Reporting of Statistical Analyses; Separate Offices; and Disciplinary Role.

Sign the online petition at RootsAction.org: http://bit.ly/2gYlXiO.

The contract of the current IPA of Fresno (Richard Rasmussen) is about to expire at the end of 2016. It is important that Mayor-Elect Lee Brand understand the importance of maintaining and expanding the power of the Office if Independent Review and possibly consider the implementation of a Civilian Review Board. At noon on January 3, 2017, Black Lives Matter-Fresno and Fresno Brown Berets, in conjunction with other community organizations, are holding a press conference at Fresno Police Headquarters (2323 Mariposa Street, 93721).

The general public of Fresno can help create the political will to make these best practices a reality for Fresno, to enhance mutual respect between the police and the public, by making their voices heard in person or online.

References:

ACLU. 1997. “Fighting Police Abuse: A Community Action Manual.” Retrieved December 17, 2016 (https://www.aclu.org/other/fighting-police-abuse-community-action-manual).

City of Fresno OIR. 2016. “Quarterly Report, Second Quarter.” Retrieved December 17, 2016 (http://www.fresno.gov/Government/CityManager/IndependentReview/Reports.htm).

City of Fresno OIR. 2016. “Quarterly Report, Third Quarter.” Retrieved December 17, 2016 (http://www.fresno.gov/Government/CityManager/IndependentReview/Reports.htm).

Garcia, Nicole and Kyra J. Neyland. 2009. “Police Lawsuits Cost City Millions of Dollars.” KMPH-KFRE.com. Retrieved December 17, 2016 (http://kmph-kfre.com/archive/police-lawsuits-cost-city-millions-of-dollars).

Guy, Jim. 2016. “Are Fresno Police Auditor, Chief Jerry Dyer on same page with use-of-force policies?”

Retrieved December 17, 2016 (http://www.fresnobee.com/news/local/crime/article110681522.html).

Hess, Jeffrey. 2016. “Role of Fresno’s Police Auditor Questioned.” Valley Public Radio, August 3. Retrieved December 17, 2016 (http://kvpr.org/post/role-fresnos-police-auditor-questioned).

Jackson, Brian A. 2015. “Strengthening Trust between Police and the Public in an Era of Increasing Transparency.” RAND Office of External Affairs. Testimony presented before the House Republican Policy Committee Law Enforcement Task Force on October 6. Retrieved December 17, 2016 (http://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/testimonies/CT400/CT440/RAND_CT440.pdf).

Krogstad, Jens Manuel. 2014. “Latino Confidence in Local Police Lower than among Whites” Pew Research Center, August 28. Retrieved December 17, 2016 (http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2014/08/28/latino-confidence-in-local-police-lower-than-among-whites/).

Lopez, Pablo. 2016. “Fresno Settles Police Shooting Lawsuit for $2.2 Million.” The Fresno Bee, November 22. Retrieved December 17, 2016 (http://www.fresnobee.com/news/local/crime/article116526138.html).

Lynch, Tim and Richard Stone. N.d. “Civilian Review Boards.” The CATO Institute’s National Police Misconduct Reporting Project. Retrieved December 17, 2016 (https://www.policemisconduct.net/explainers/civilian-review-boards/).

Mazerolle, Lorraine, Sarah Bennett, Jacqueline Davis, Elise Sargeant, and Matthew Manning. 2013. “Legitimacy in Policing: A Systematic Review.” The Campbell Collection Library of Systematic Reviews 9. Oslo, Norway: The Campbell Collaboration. (Available at https://www.campbellcollaboration.org/library/legitimacy-in-policing-a-systematic-review.html).

McCarthy, Justin. 2014. “Nonwhites Less Likely to Feel Police Protect and Serve Them,” Gallup: Politics, November 17. Retrieved December 17, 2016 (http://www.gallup.com/poll/179468/ nonwhites-less-likely-feel-police-protect-serve.aspx).

PERF. 2015. “Re-Engineering Training On Police Use of Force.” Critical Issues in Policing Series, Police Executive Research Forum, Washington, D.C. Retrieved December 17, 2016 (http://www.policeforum.org/assets/reengineeringtraining1.pdf).

President’s Task Force on 21st Century Policing. 2015. “Final Report.” Retrieved December 17, 2016 (https://cops.usdoj.gov/pdf/taskforce/taskforce_finalreport.pdf).

Sheehan, Tim. 2016. “More firepower, horsepower approved for Fresno police.” The Fresno Bee, December 15. Retrieved on December 17, 2016 (http://www.fresnobee.com/news/local/article121238798.html).

Stevenson, Bryan. 2006. “Confronting Mass Imprisonment and Restoring Fairness to Collateral Review of Criminal Cases.” Harvard Civil Rights-Civil Liberties Law Review 41(Summer):339–367. (Available at http://eji.org/reports/confronting-mass-imprisonment).

*****

Laura Garcia (Political Science, laurg7@mail.fresnostate.edu), Michael Ballin (Sociology, im_michael1@mail.fresnostate.edu), Carlene Merino (Sociology, carlene8320@mail.fresnostate.edu), & Matthew Fosberg (Public Service Administration & Community Relations, blazer8580@mail.fresnostate.edu) are students at California State University, Fresno. Feedback and additional reference information for this article were provided by Dr. Matthew Ari Jendian, Professor of Sociology, California State University, Fresno.