By Hannah Brandt

Most Fresnans do not know that an internationally renowned human rights activist spent many years among us as a classmate, colleague, and neighbor. I certainly did not until I went to Stanford University to hear Virak Ou, a human rights activist who had come all the way from Cambodia. As I listened to him talk, I was unaware Ou previously lived in Fresno for 10 years.

As I found him informative and engaging, I began following him on Facebook. That was how I learned he got his B.A. in economics from Fresno State and graduated from Roosevelt High School, which is my alma mater as well. It’s not surprising we didn’t know each other since the year he graduated Roosevelt had ballooned to 4,500 students and I was a lowly sophomore. Fortunately, that fact did not prevent him from agreeing to talk to me.

Ou now lives in the Cambodian capital of Phnom Penh, where for more than a decade he has been tirelessly fighting for human rights in leadership positions with the Cambodian Center for Human Rights (CCHR) and the Alliance for Freedom of Expression in Cambodia, the latter of which he founded. In 2007, he won the Reebok Award for Human Rights for his freedom of expression campaign to set free human rights activists (like then CCHR president Kem Sokha) incarcerated for criticizing the government. Fortunately, this yellow ribbon campaign was successful.

He continues to collaborate with other humanitarian groups to achieve greater rights and freedoms for the Cambodian people, prompting praise from the U.S. ambassador to Cambodia, William E. Todd, and winning invitations to speak with policymakers like Hillary Clinton and members of the United Nations. With the rise of human rights abuses by government forces not to mention those by international corporate and nonprofit organizations, in addition to escalating tensions among Cambodian political factions, the people need steadfast advocates like Ou.

At Roosevelt, I got to know many immigrant students, some of whose parents had brought them to the United States from Southeast Asia in the years following the Vietnam War. Most of my friends were babies then, with little to no firsthand memories of their motherland. Ou was 13 when he finally reached American soil in 1989. While I was preoccupied with trying to get perfectly scrunched hair and socks, Ou was trying to wrap his head around the concept of a book report: a very different struggle than fighting to get enough to eat so that his ribs wouldn’t show through his clothes.

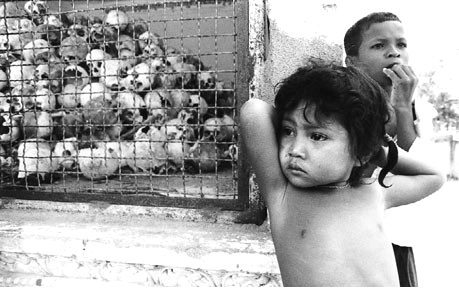

Ou was four when the Communist Khmer Rouge regime fell in 1979 as Vietnamese forces captured Phnom Penh. The regime had instituted agricultural programs that forced all citizens, regardless of experience and skill, to farm for their food or starve. Middle-class professionals, the elderly and disabled, ethnic minorities and those accused of political dissent were forced into labor concentration camps, tortured and/or murdered under Pol Pot’s ruthless dictatorship. In the 1980s, Ou sometimes stumbled on one of 20,000 mass graves—remnants of the Killing Fields—or found skulls in the trash.

In 1979 and 1980, 650,000 Cambodians starved to death. One to two million people died under the regime, half of them killed en masse. People in Ou’s village often found jewelry cast off after it had been confiscated or left on dead bodies by the physically brutal regime. Items that are precious commodities in most societies were worthless in this fanatical Communist state. Those desperate Cambodians who had survived massacre and starvation would exchange the gems for rice because food was hard to come by. None of this was alien to a small boy who had to flee soldiers across a creek before learning how to swim.

When Ou was nine, his family had to flee from resistance camps where people were under strict military watch to refugee camps where what little food could be had was terrible. His father had been in the army of Lon Nol’s American-backed Khmer Republic, which overthrew Prince Sihanouk in 1970, but was ousted by the Viet Cong–supported Khmer Rouge in 1975, less than a year before Ou was born. As part of the Khmer Republic army, his father was one of the first to be executed by the Khmer Rouge. Sadly, this meant Ou would never know his father. Lon Nol successfully gained refuge in California 10 years before Ou’s family would make it safely to Fresno.

In 1988, 300,000 Cambodians were living in refugee camps on the Thai border. Ou would have been one of them. Cambodia had been divided up in 1980 between the Khmer Rouge, the Khmer People’s National Liberation Front (former Lon Nol supporters) and the Armée Nationale Sihanoukiste (ANS; Prince Sihanouk’s former officers). Pol Pot remained the head of the Khmer Rouge through 1985 and was not arrested for war crimes until 1997.

The Vietnamese military stayed in Phnom Penh until 1989, which stirs up tensions between the neighboring countries today. When Ou’s family finally attained refugee status in the United States, he was placed in a standard seventh-grade class. He had learned to speak some English in the refugee camps but could not write it. Without extra guidance, he was completely lost in his American classes at a time when adolescence makes life tough enough.

Despite his early difficulties, Ou was able to not only survive in American schools but also to thrive in them. After attaining his M.A. in economics at San Jose State, he went back to Cambodia, serving the people through his knowledge of law. He returned to a country that is still racked by political turmoil. Although Khmer Rouge leaders are long out of power, Cambodia’s current leadership has become increasingly oppressive. Hun Sen, a Khmer Rouge defector, came to power the same year Ou settled in America. He is still in power.

The government, which controls most of the press, has been accused of election fraud and corruption and uses violence against garment workers striking for living wages and those protesting for political rights.

In 2012, Ou was accused of “incitement,” after consulting with villagers locked in a land dispute with the government in 2009. Caught in the crossfire between angry protesters and harsh officials, Ou continues to voice his concerns about growing anti-Vietnamese sentiment in Cambodia, stoked by some anti-government protesters who view Hun Sen as a pawn of the Vietnamese government. In February, an ethnically Vietnamese man was beaten to death in Phnom Penh by an enraged crowd that chanted “yuon,” a regional term with racist overtones.

Ou has remained optimistic, open-minded and nonpartisan in his approach to activism. He has challenged others to use the Cambodian parliamentary and legal system to attain greater rights rather than resorting to the violence that has had such tragic consequences in his nation’s history and Ou’s own personal experience.

At a TED (Technology, Entertainment, Design) Talk in 2011, he voiced concern about activism’s “image problem,” whereby most people wait for heroes to emerge instead of initiating action themselves.

Ou’s former Fresno neighbors would welcome his leadership style in a gridlocked Washington, D.C., and here in California, where severe drought is fomenting renewed water wars. As he says, “The public will not listen to a leader who is not principled or anyone who is not willing to compromise.” Fortunately, the public is listening to him.

***

Hannah Brandt is a freelance journalist in Fresno. Contact her via Twitter @HannahBP2. You may follow Virak Ou on Facebook, Google Plus and on Twitter @ouvirak.